#1: The Great Globalization is Ending

How the system has worked over the past 50 years and how it's breaking

[Author’s note: This turned out to be longer than I thought even though I tried to use bullet points, visuals, and charts to make it easier to read. Would appreciate feedback on content, writing, and anything else!

If you like this, please share! Newsletter rely on organic growth through the community of readers!

If you didn’t, let me know why!

Twitter: @mtaa324]

Introduction

In this piece, I want to provide an overview of the system that has shaped our world over the past 50 years, without commentating on its virtues or suggesting what should come next. It is important to emphasize how critical this particular setup has been to essentially every aspect of our lives, which hopefully lends credence to the value of understanding it properly.

This is meant to serve as a broad framework that can tie various concepts together. In subsequent essays, I will deep-dive into various parts of this framework (e.g. energy, supply chains, finance, etc.) to hopefully illustrate the complexity and interdependency of these threads.

In keeping with my attempt for brevity, here is a summarized list of some of the outcomes this system has achieved over the last five decades:

Structurally low inflation in the Global North and high (or volatile) inflation in the Global South

Manufacturing being offshored to the Global South, creating a platform for countries like China and Vietnam to rapidly develop, while also creating a development trap

Increased financialization and financial interconnectedness of the global economy, perpetuating risks of financial/debt crises

Cheap and easily available goods from across the world, and just-in-time manufacturing

Relative degree of geopolitical order in a unipolar world

The discourse around this global system is centered around political ideals (e.g., democracy, liberalism, free markets, etc.) which, in my opinion, abstract away from the material reality that underlines these concepts. Energy resources, raw materials, manufacturing capability, military strength, etc. are the main cogs that constitute the engine of the system - they constitute the base layer - and so let’s understand how they all fit together.

Examining the global system

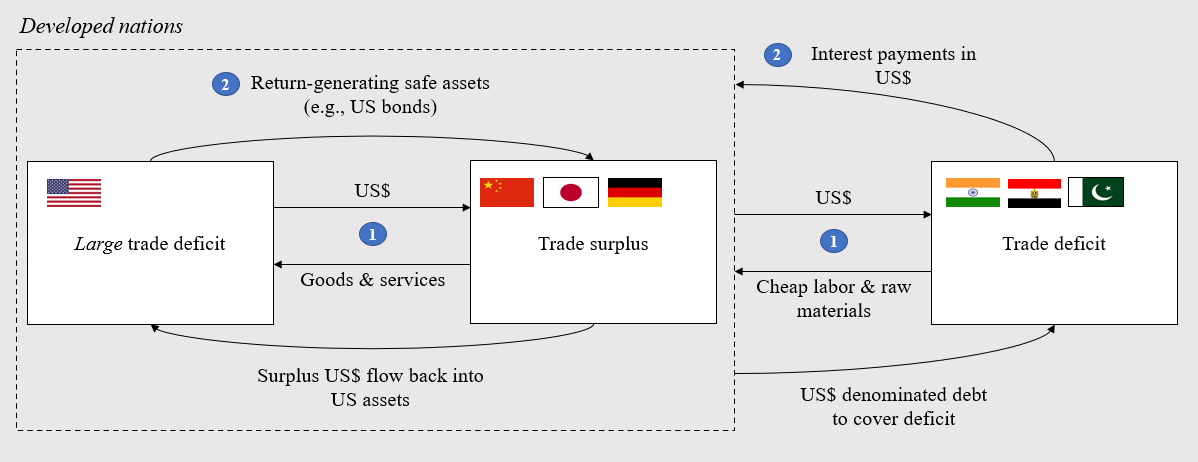

A simple way to understand the global system is to think of three main nodes: financial capital, manufacturing, and energy/commodities. All the major states largely play a role in keeping one of these nodes going, although there is significant overlap (e.g. Japan is a majorly liquidity provider in Asia, the US is also a major commodity and manufacturing hub, and so on).

To illustrate, let’s look at some facts about the iPhone’s supply chain:

- Apple uses 60-70 elements of the periodic table (that’s a huge variety of raw materials!), with suppliers in 43 countries covering 6 continents[1]

- Most of the components are assembled in places such as Germany, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan

- These are then assembled predominantly in China and exported mostly to the Americas and Europe for consumption

There are 5 factors that enable this system to function smoothly:

1. US$ as the global reserve currency. This means that all international contracts and liabilities are denominated in US$, even between non-US entities. Countries are constantly trying to accumulate US$ either through trade surpluses (exporting more than importing) or borrowing through capital markets. The benefit of this is that all countries agree on a single currency which makes price-setting easier and requires trust in a single country – the US – which is also the global hegemon and can back up its currency with military strength. This of course means that the US has exorbitant privilege through dominating the plumbing of global finance and being the sole supplier of liquidity.

“The dollar is our currency, but it's your problem” - John Connally, Treasury Secretary 1971 to his G-10 counterparts

2. Cheap energy from OPEC+ countries and others (e.g. US, Canada, Norway). As recent events are finally bringing to light, access to cheap energy for industrial processes and supply chains are critical in keeping inflation low and producing goods at the rate with which we have become accustomed. Oil and gas are incredibly energy dense and can be globally transported, which makes them hard to replace as energy sources. Given that supply of these hydrocarbons is concentrated in the hands of a few countries, geopolitics has been crucial to maintain steady supply and low prices (e.g., look at the Germany’s troubles once access to cheap Russian gas went away). Same is true, to a lesser extent, for raw materials such as copper, lithium, rare earth metals, etc. but this is a growing area of concern as well.

3. Population boom and labor influx to produce low-cost, high-volume goods. Think of the speed with which we consume (and waste) items such as fast fashion, mobile phones, packaged food, etc. because they are readily available and affordable. There have been three major sources of increased labor supply: women entering the labor force post WWII; baby boomers in 1970s; integration of high-population Global South into the global system. Given the aging populations in most developed countries, offshoring to Global South countries such as Vietnam, India, etc. has been critical, buoyed by the ease of the Great Globalization.

[Imperative to mention here that “cheap labor” doesn’t do justice to the prevalence of terrible working conditions and labor exploitation in many countries that brings this cost down.]

4. Export oriented development as most countries fight to achieve a trade surplus while others are able to maintain high consumption rates without paying the “real” costs, such as environmental pollution, low wages, etc. There are two parts of this:

Some richer nations that export high-value added goods achieve a trade surplus and then recycle the US$ they earn back into US assets (safe haven benefits!);

Other developing nations wrestle to achieve a surplus but are typically stuck in a trade deficit cycle because they export low-value added stuff (back to cheap labor) and need more US$ than they earn for either critical things like food and energy or capital goods such as technology.

5. Trust and geopolitical stability with a unipolar world that has the US at its center. On the financial side, this has maintained trust in the US$ and most participants have readily engaged in this game of acquiring US$ assets in order to survive/grow. On the real economy side, the expansive US military presence has been critical to the pricing of energy in US$ (petrodollar), securing safe shipping lanes for efficient supply chains, ensuring/forcing countries with raw materials to remain open for trade, etc.

Cracks in the system

Dollar weaponization

Sanctions: One of the major blows the status quo has been the weaponization of the US$ by the US for strategic interests. While this is arguably not a new phenomenon, the explicitness of recent events, coupled with the now obvious emergence of a potential competitor (either China on its own or a larger bloc led by it), has made countries reassess their dependence on this system. This “weaponization” narrative officially took hold after the US led the charge in freezing Russia’s US$-denominated assets following the invasion of Ukraine.

Other security related examples include freezing $7B of Afghanistan’s funds and attempting to block access to SWIFT – the basic infrastructure that enables cross-border payments – for Iran and Russia.

Swap lines: At a higher level, the US has used dollar swap lines to support its strategic allies in times of crisis while letting other countries scramble over not having enough US$ liquidity (remember, countries need US$ to engage in trade, so a US$ shortage can mean not having the liquidity to import food, energy, medicines, etc.).

A swap line is simply a direct line between the central banks of two countries that allows easy exchange of currencies.

During the 2007-8 financial crisis and the Covid crisis, the US extended swap lines to the same handful of allies (table below). The question is not whether the US is within its right to do so, but simply that such policies, especially since they were made in coordination with the State Department, dilutes the trust broader participants have in the system and force countries to seek alternatives.

Domestic vs international tradeoff: Lastly, the appreciation of the dollar against other currencies and subsequent currency crises this year could be seen as another form of (indirect) weaponization. With inflation running at 40-year highs, the Fed has been raising interests and tightening monetary conditions, thereby reducing US$ liquidity in the system.

This allows the US to export inflation (as US$ appreciates, imports to the US become cheaper) but since most of the world owes debt in US$, this puts pressure on those countries at a time when global growth is already subsiding and the opportunity to earn US$ through exports is decreasing.

Geopolitical fracturing

US-Russia front: The second major issue is the breakdown of global trust and the onset of heightened tensions between countries. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has rekindled a Cold War dynamic with a Western bloc, Russia + allies, the non-aligned countries. Not only has trust in the system begun to erode, as countries such as Saudi Arabia and India seek to balance their own priorities with complying with Western sanctions on Russia, but there are also visceral energy shocks that the world is having to deal with as Russian commodities go off the market, at least officially.[2]

The breakdown of the Nordstream pipeline that supplied Russian natural gas to Europe, the insistence of OPEC+ to engage in oil production cuts in an attempt to raise the price, and the war-related supply chain disruptions have all led to skyrocketing energy prices, especially in Europe.

[Yes, those prices have come down in recent weeks but arguably only temporarily and at huge cost]

As a second order impact, the Global South has suffered as the EU dramatically outbid these countries in the energy markets and redirected resources, leading to blackouts and crises in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, etc.

US-China front: The US has also intensified its policy of containing China with the recent semiconductor chip ban, adversarial rhetoric, and announcements regarding onshoring supply chains. This is easier said than done however because China is a major manufacturing hub, a leader in next-generation technologies (e.g. robotics and AI), and controls the supply chain for critical raw materials (90% of the rare earth metal and 40-70% of copper, lithium, etc.).

“We’re not reading the American press, we actually buy the [China] story,” UBS chair Colm Kelleher said this past week. He also said global bankers are “very pro-China”. Note: UBS is the world’s biggest wealth manager.

The impact on the US$ system is self-evident, especially because the Yuan is a natural competitor to the US$, but the more disruptive ramifications are reductions in energy availability due to geopolitical splits (e.g. Saudi Arabia’s recent snub to Biden while showing warmth towards Xi), security of the South China Sea which is a critical trade route, and the reduced access of Western companies to China’s manufacturing capabilities (including the cheap labor) without a direct alternative.

So what next?

I will avoid speculating on outcomes but there are some developments that are largely baked in at this point.

Price volatility: Over the past 40 years, inflation in the Global North has been perennially low, to the point that policymakers have failed to get it higher despite their best efforts. But as supply chains break down, trade deglobalizes, and energy becomes scarce/weaponized, producing things will definitely get more expensive. Also, war is highly inflationary, so the spectre of that risk looms large.

On the other hand, demographic trends are worsening, technology is making things cheaper, and central banks are, at least for now, hell-bent on inducing a recession by destroying demand to bring down prices. So there are also strong deflationary tailwinds as well.

Debt crises: Everywhere you look, indebtedness is high. And by high, I mean really really high. In particular, the private sector (both firms and households) and developing nations have high levels US$-denominated debt. An appreciating US$ and slower economic growth will force many actors towards default, and with a hyper-financialized system, that poses major systemic risk. This is all very jargon-y but debt crises have a catastrophic impact on countries (mass unemployment, food/energy shortages, etc.).

[It’s crazy if you think about that just last month, the UK pension system almost blew up and had to be rescued at the last minute. Developed economy (strong capital markets and what not) + pensions (supposedly safe) things are only starting.]

Regionalization: The resurgence of OPEC+ to center stage, return of the non-alignment movement being led by major players such as India, Brazil and Saudi Arabia, and the possible formation of an OPEC equivalent for raw materials (with Indonesia, Chile, etc.) all help contribute to breaking down the current unipolar system. Will China replace the US at the unipolar helm? Unlikely. Regionalization in terms of supply chains, currencies, trade, etc. is likely coming.

Let me leave you with 3 wild charts that show, despite this tectonic shift just kicking off, how crazy things already are and how normal people are directly impacted.

US 30-year mortgage rates

Mortgage rates are surging to levels not seen since the financial crisis. It is not just the rate itself but the speed with which these rates have risen that is dangerous. Higher rates mean less affordability of housing, slower construction, and reduced resale value. As they say in the US, housing is the economy. It employs 10-12M people, contributes 15-18% to GDP, is major source of collateral for borrowing, etc.

German inflation

Source: Twitter (@schuldensuehner)

If there was one country that made low inflation the core of its economic policy, its Germany. And yet the past year has been astronomically high levels of inflation because of the energy crisis (45% producer price index!). This hurts small businesses and citizens as they struggle to pay the bills. Imagine energy rationing.

[Europe is facing an unusually warm winter which has helped it avoid a serious winter crisis]

While this winter may be reasonable, jobs are going to be lost as deindustrialization is forced in a major manufacturing economy through reduced cost-competitiveness.

Japanese Yen

The Yen is one of the most important currencies globally, especially due to its outsized role in providing financial liquidity in Southeast Asia. The depreciation of the Yen against the US$ has been the main chart people have been focusing on all year because it represents how quickly a currency crisis can ensue – and this in a highly developed country with barely any US$ denominated debt and a US$ swap line. A 40%+ devaluation means things becoming more expensive (remember Japan is a major energy importer) while also forcing other related countries – especially South Korea and China – to also devalue their currencies to maintain competitiveness.

(The Yen against the US$ is at the same level that it was in 1998 – Asian Financial Crisis anyone?)

Afterthoughts

There are just two things I want to say here: firstly, systems take decades to emerge, and hence take a long time to unravel aswell. It’s important to know what to look for rather than getting the timing right. Secondly, this isn’t about doom and gloom. All systems have their pros and cons, but history tells us that transition periods are volatile and messy, and we are historically due for a transition.

I hope this piece was able to convey the complexity of the current system and how it all fits together. Now throw in stuff like ecological collapse (droughts, floods, heatwaves), rising populism, etc. and its a dangerously high-stakes game.

For the next few pieces, I want to get into the details of some of the concepts introduced here, but would love feedback on which topics to prioritize (other feedback too). My current list includes:

Primer on the global energy situation (reliance on O&G, supply chain, scale of energy consumption, etc.)

Primer on global finance/macro (US$ as reserve currency, role of bonds, currency crises, how money gets created and moved around, systemic risk)

Finance & investing (challenging the recency bias of “stocks always go up”)

Primer of ecological collapse and how “climate change” is just a small portion of it

Degrowth 101 - what is it really about

Japan - why its importance is misunderstood and how it could represent the future for many Global North countries

Introduction to the concept of Fictitious Capital

[1] While Apple does not disclose the source for all the raw materials, it is legally required to disclose this information for “conflict materials” – Tin, Tantalum, Tungsten, Gold. Here’s the official report which includes the country breakdown for these elements: https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple-Conflict-Minerals-Report.pdf

[2] Marko Papic makes a great point here that the Western sanctions on Russian energy sources are intentionally incomplete and allow for those resources to enter the global market circuitously. Link to a great podcast:

Thank you for very insightful analysis. All your pieces is fantastic.

I have been working on an article on production of surgical equipment in Sialkot for the western marked. I have been thinking that the levels of healthcare we have in the north is possible because of globalization. With deglobalization the first sector the feel squeeze is healthcare. Its "crisis" in some parts of western healthcare (not compared too global south).

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/dec/14/a-ticking-time-bomb-healthcare-under-threat-across-western-europe

Healthcare is thought about as a service sector but its very resource intensive. "The health-care sector's share of the national footprint was highest for material extraction"

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00244-3/fulltext

All this resources comes from the global south. Including child labour. One more example of the levels of healthcare in western countries made possible by exploitation. Conspicuous consumption is worse but healthcare has specific complications.

In degrowth movement they are talking about resources to healthcare but I am sorry to say that the needs is unlimited. The more we treat the more needs there is. https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2015/03/who-has-misled-trond-mohn

It is possible to gradually get better but with the cost of even more pollution such as PFAS an other endocrine disruptors. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00134-023-06994-0

I wold like to talk to you about my thoughts about globalization and healthcare. Is it possible?

Fantastic piece. If I could add a request to you list it would be including the housing/real estate/land circuit of capital in your analysis of the world system. Thanks!