#10: We are living in a material world

Primer on raw materials: decarbonization, geopolitics, the mining & trading industry, and more.

[Author’s note: This is a long piece covering various sub-topics. Each of the three sections can be read as standalone so feel free to skip to the one that interests you the most if you don’t have time to read the whole thing — although I hope you do go through it!

Also, since I last wrote a piece I have had the privilege of appearing on multiple podcasts to talk about energy, the Global South, degrowth, etc.

As always, feel free to reach out with questions, feedback, counterpoints, etc. I tweet at @mtaa324]

Introduction

We live in a material-intensive world. Despite all the hype about digitization (metaverse, AI, cloud, etc.) or about a services economy, this great civilization of stuff that we have built has required copious amounts of raw materials — and continues to do.

The amount of new material added every week equals the weight of 8 billion humans — yes, that’s every week!

Rather than slowing doing, this material consumption is only going to accelerate going forward, driven by 4 potential factors:

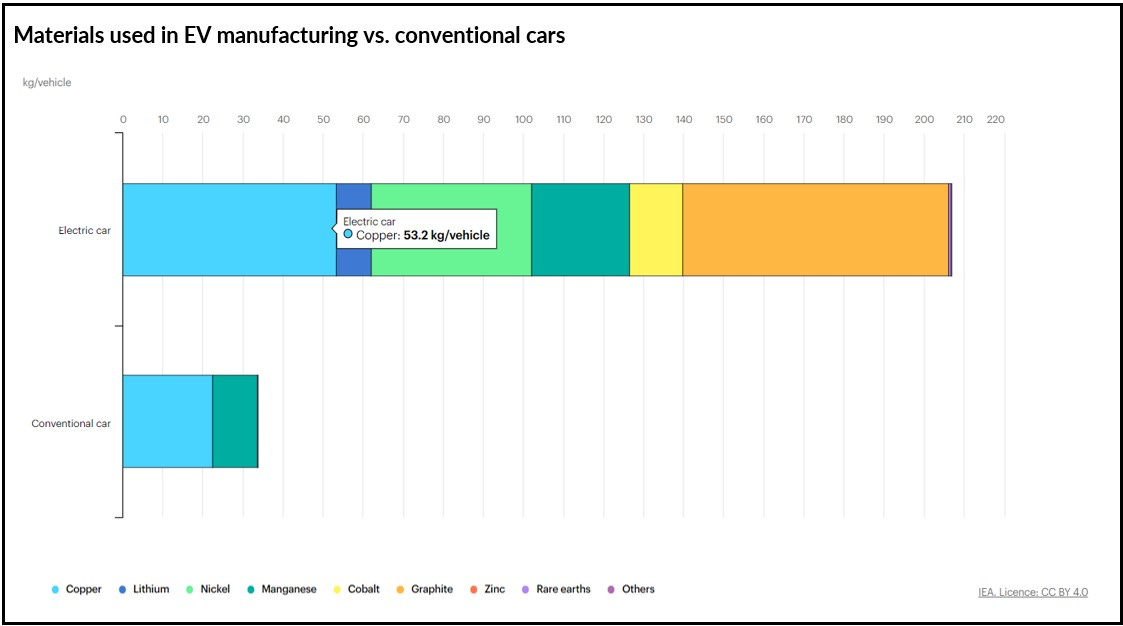

Decarbonization = re-materialization: Renewable energy, EVs, etc. are require an incredible amount of materials, both to build the devices themselves but also the supporting infrastructure (e.g. long-distance electricity transmission lines, EV charging, etc.). The energy may be free, but our ability to harness it isn’t. This isn’t just about the climate; any climate-skeptic readers should note that this is also about energy security, air pollution, etc., as was realized even by the conservative, anti-climate Democratic senator Joe Manchin

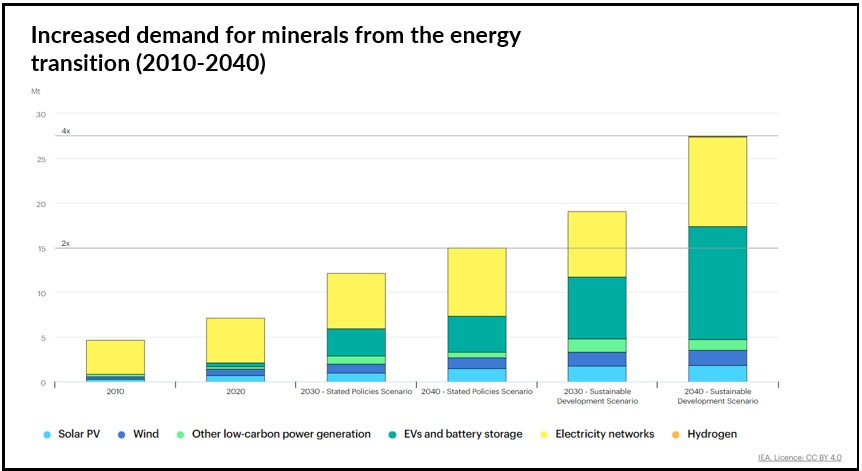

Source: IEA Onshoring & industrial policy: If globalization led to economies of scale, then the attempts to de-globalize should do the opposite. China already had a robust onshoring and domestic manufacturing policy; now we see the EU, US, India, and making emerging economies follow suit with large, even unprecedented industrial policy programs. That means more mines, more factories, more equipment, etc. — all material intensive.

Tackling poverty & inequality: There’s no question that the rich consume orders of magnitude higher resources and energy that the non-rich. Hence, both from a climate perspective but also just as a socioeconomic moral imperative, redistributing wealth is paramount. However, this is not as simple as just taxing away $1T — as an example — from the rich and distributing across the non-rich because especially as lower income levels, the material intensity of consumption is quite low. Therefore, more income will mean moving to higher material intensity forms of consumption (e.g. housing, transportation, technological devices, etc.). This means more demand materials. Just think of how much material it will take to build proper homes for the 1.6 billion people globally who are either homeless or in insufficient housing.

War: If there’s one thing that leads to sudden, sharp increases in raw material consumption, it’s war. I don’t need to explain why war itself, and its consequences (rebuilding), are material intensive. ~6% of global emissions come from this industry. At a time when geopolitical tensions are rising across multiple fronts, we shouldn’t forget how our already strained biophysical systems would suffer if more escalations emerge.

By 2040, it is estimated that demand will be 2x-4x of 2020 levels — and this is just from the clean energy transition. For some specific materials, such as rare earth metals, the demand is expected to jump as high as 10x!

It is not surprising then that in 2023 we have seen the struggle over raw materials escalate. Numerous countries have announced that they will no longer allow these material resources to be cheaply mined and then exported for foreign consumption. Chile, Namibia, Indonesia, Zimbabwe, China, etc. have instated policies, or at least raised the prospect of, restricting the export of materials such as copper, lithium, aluminum, and so on. The recent news coming out of Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali points towards the countries reclaiming ownership of their resources, much to France’s detriment.

In this piece, I provide a primer on the raw material ecosystem. Similar to the one on oil, this provides a broad overview across 3 fronts:

Why are minerals & metals (raw materials from here on) critical

What does the industry look like

What are the geopolitical dimensions

To take a step back, I started this newsletter as a project to explain how the base layer of our system works. Thus far, we have covered energy and the monetary system. The third, and final, piece of the base layer are raw materials.

We cannot access or meaningfully transform energy without having the raw materials to do so; concurrently, we need energy to access and use the raw materials. This is how those two pieces fit together. Money, as I have mentioned in other pieces, is the tool that connects market participants together to allow this activity of using energy and raw materials to make stuff happen. Energy and raw materials are physical concepts so they are slightly more fundamental, but I’d argue that those two together with money form the base layer of human civilization.

I. The criticality of raw materials

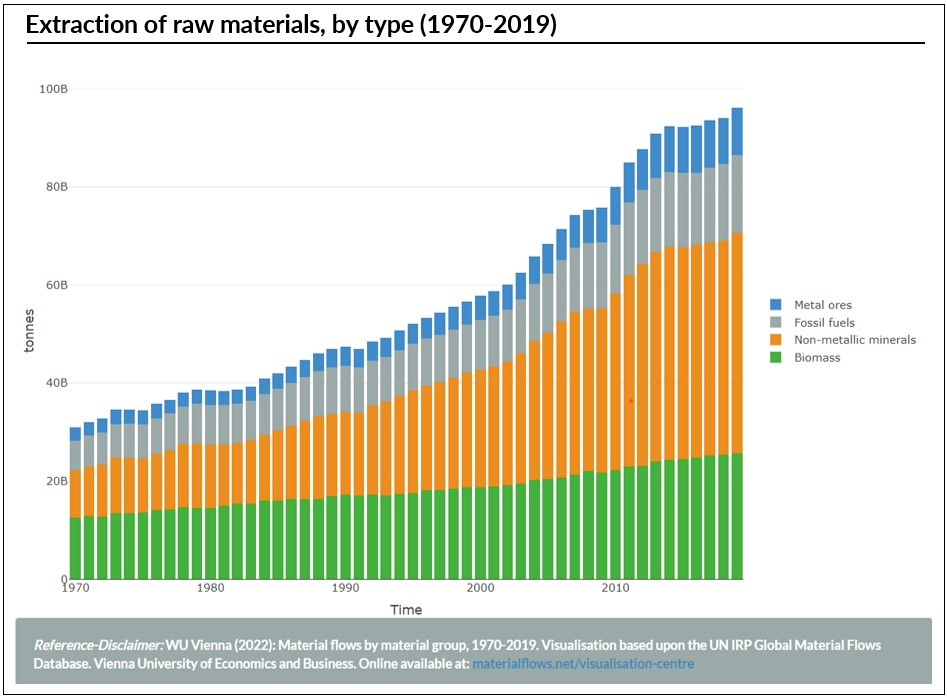

Since this is a very broad sector, let’s define some basic categories. Raw materials can be broken down into metallic, non-metallic (sand, gravel, etc.), biomass (lumber, food commodities, etc.), and energy resources (fossil fuels). In 2021, it is estimated that ~100 billion tonnes of raw materials were extracted globally.

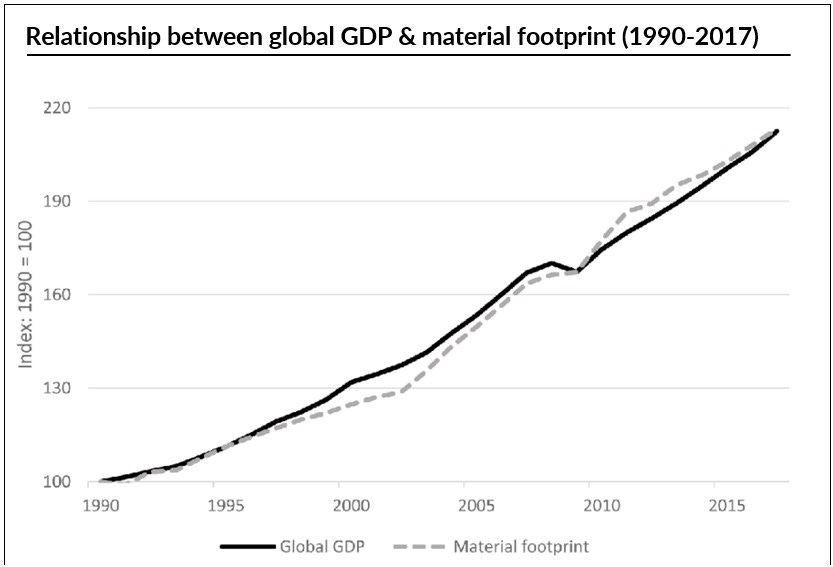

As with energy, raw materials have a highly positive correlation with GDP. This intuitively makes sense — in a consumption driven economy, more economic activity will require more materials to be extracted and consumed. Remember, we live under a system that requires exponential growth!

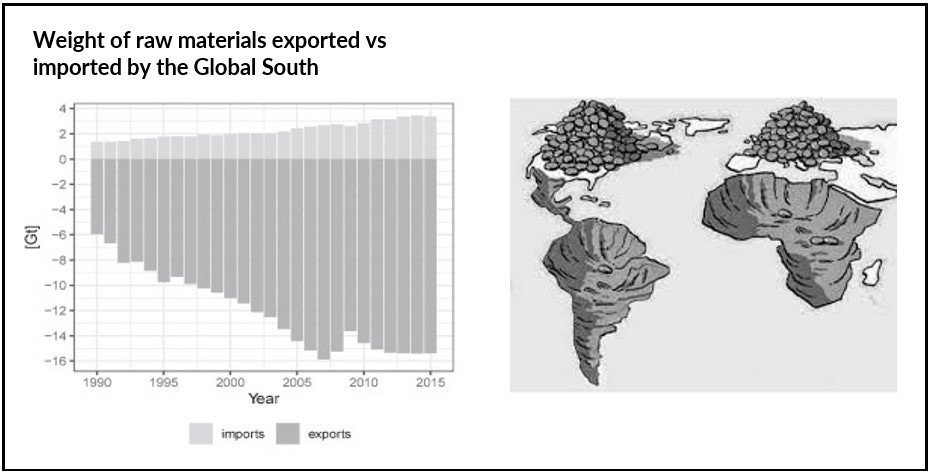

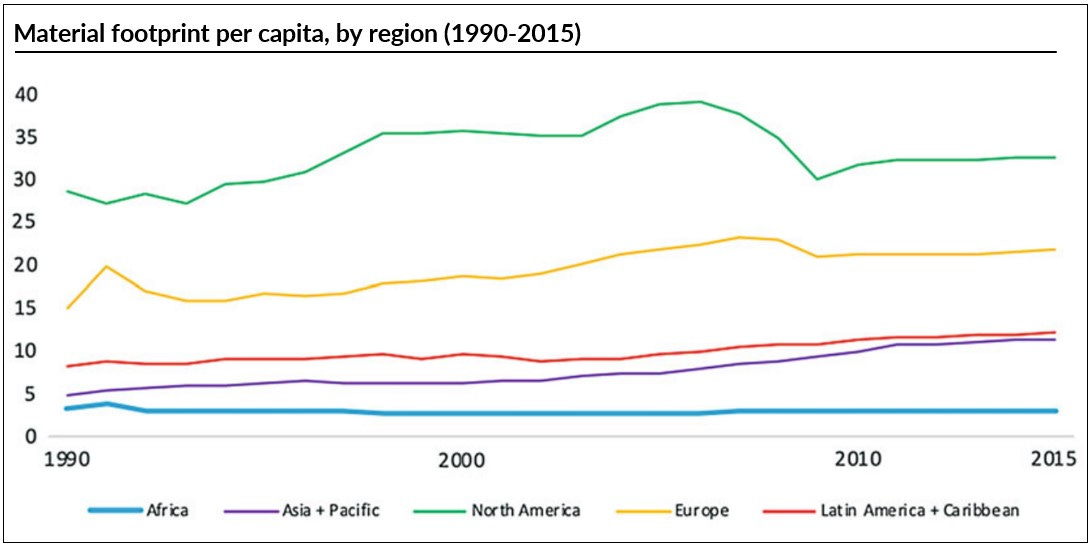

It is also important to recognize that while metrics such as CO2 emissions per capita are falling in richer countries — something they use to shift the climate onus onto countries like India and China — material footprints have remained constant at an exceedingly high level for the Global North. So at the top when I said humanity is adding a staggering amount of new materials every year, it’s mostly the Global North and the global top 10% of wealthy people.

It is clear that we use a lot of, and increasing year-on-year, amount of raw materials. Our economic system of growth depends on it. These materials are used for everything around, ranging from food, housing, roads, buildings, smartphones, cars, etc. to weapons, heavy machinery, and so on.

In order to dive deeper into this sector, I cannot generalize across all 4 categories of materials. Therefore, in this piece I will focus on metallic materials mostly because of their importance to decarbonization, technological development, and heightened geopolitical dynamics.

Even within metallic materials, we are talking about a remarkably broad array things (the following classification is somewhat arbitrary because the use and importance of these materials is context dependent):

Precious metals (e.g. gold, silver, platinum): These elements are used both for non-industrial — such as jewelry or as an monetary store of value — and industrial purposes. In terms of weight, these are a relatively small proportion of the total amount of metals mined.

Industrial metals (e.g. lead, copper, iron, aluminium): Our industrial civilization depends upon vast quantities of these metals because everything we build requires them. Just stop to think about how much iron is need to make all the steel we use in constructing infrastructure, or the amount of copper use in all the electrical wiring in the world. In fact, iron ore makes up more than 90% of the total metals mined annually. No wonder Vaclav Smil called steel one of the 4 pillars of modern civilization.

Critical metals (e.g nickel, lithium, cobalt): The use of the word critical here is of course context dependent. These elements have been classified as such primarily because of their supply chain risks, and their growing demand due to electrification and decarbonization. Batteries, for example, which are the key to unlocking renewable energy, EVs, etc. are one of the largest use-cases for lithium and cobalt.

Rare earth metals (e.g. dysprosium, neodymium, cerium): This is formally a group of 17 elements. Technically they are not rare, meaning that there isn’t a shortage of deposits in the Earth’s crust. Instead, the fact that they are found in low concentration deposits makes them hard to mine, leading to their rareness. They also have special properties (e.g. high degree of magnetism) which makes them critical for so many existing and upcoming technological developments, ranging from cellphones and steel alloys, to EV motors and wind turbines.

Lifecycle of these materials

Much like the story with oil, the process of extracting metals and making them ready for commercial use involves multiple steps.

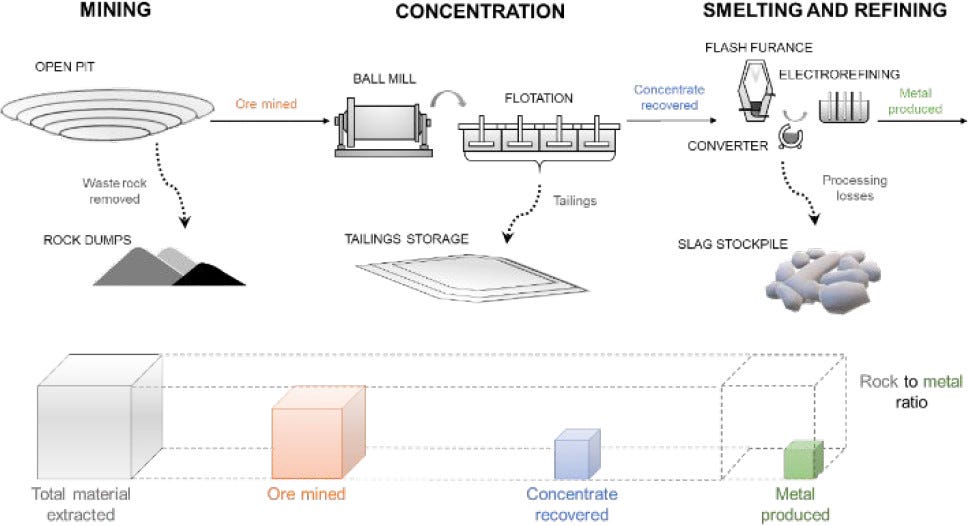

Mining: Metals are usually found in ores, which are themselves found in rock deposits across the Earth’s surface. When ores are not too deep, surface mining methods such as open-pit mining or strip mining are used. Although less invasive, these require stripping away or digging through the top layer of soil and rocks to access the minerals below. For deeper ores, extensive digging and tunnels through the Earth’s surface are used to access and excavate the ores.

Concentration: Once the rocks containing the ores are excavated, the process of removing impurities is undertaken. Depends on the type of ore, various methods are employed, including hand-picking (the traditional way), hydraulic washing (use high-pressure water streams), and chemical reactions. This process results in significant waste materials called tailings.

Refining: This involves a vareity of activities that prepare the metal for commercial activity, including purification, crushing, grinding, etc. Electrolysis, distillation, chemical reactions, and heavy machinery are all used in this process.

Post-use: Most conversations stop at the point of end-use but it is important to understand what happens to these materials afterwards. Not only does our use and throwaway model require increasing amounts of material mining, but it also contributes to waste as these materials end up in landfills. Some products, such as steel, have high recycling rates (40% of annual steel production is recycled), while others have rates as low as 1%. One of the problems with recycling is the feasibility of going through our waste products (small and scattered) and going through the tedious process of extracting tiny amounts of materials.

There are 3 main takeaways that I would emphasize from this process:

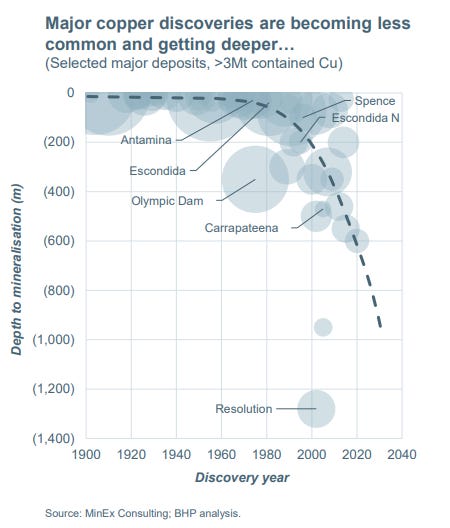

Ease of access: When it comes to any type of material, the industry terminology differentiates between the total estimate of that material on Earth (called material resources) and the total amount of that material which is accessible given the current technological and cost dynamics (known as reserves). So for example, the estimated copper resource is 5,000 million tonnes but the copper reserves are only 870 million tonnes. Mining deeper ores requires considerably more energy and resources, henceforth raising the cost of these metals. Thus far we have been tapping into the low-hanging fruit but as our current system goes on, we are forced to shift towards tougher mine practices (e.g. ocean mining). And that isn’t going to be cheap, easy, or reliable.

Waste rocks: The indsutry used the term of rock-to-metal ratio (RMR) to determine how much rock needs to be mined to give 1 unit of metal. Although the ratio varies significantly across metal type, the numbers range from 1,000,000:1 for gold and silver to 10:1 for iron and aluminium. That’s a lot of waste rock (known as tailings) that are left behind and then need to managed. Apart from the energy and space required to store these tailings, there are also environmental damages such as landslides or water pollution (as rain water mixed with mercury, sulfur and other toxic chemicals from tailings and pollutes water bodies — know as leeching).

Ecological damage: Apart from tailings and even the climate impact from fossil fuel across the metal production process, there are considerable other forms of damage that occur. For example, the loss of biodiversity and damage to ecosystems occurs both because of the intense impact mining has on the land (think back to those pictures — top soil stripping, explosions, chemicals, etc.) and because upto 50% of mining occurs in relatively close proximity to ecologically important sites. Another major source of damage is water pollution at numerous points of the process. Toxic and radioactive materials are released through mining the rocks, the chemicals used in mining, refinings, etc. seep into underground water and other water bodies, the disposal of wastewater isn’t done properly, etc.

II. The geopolitics of metals

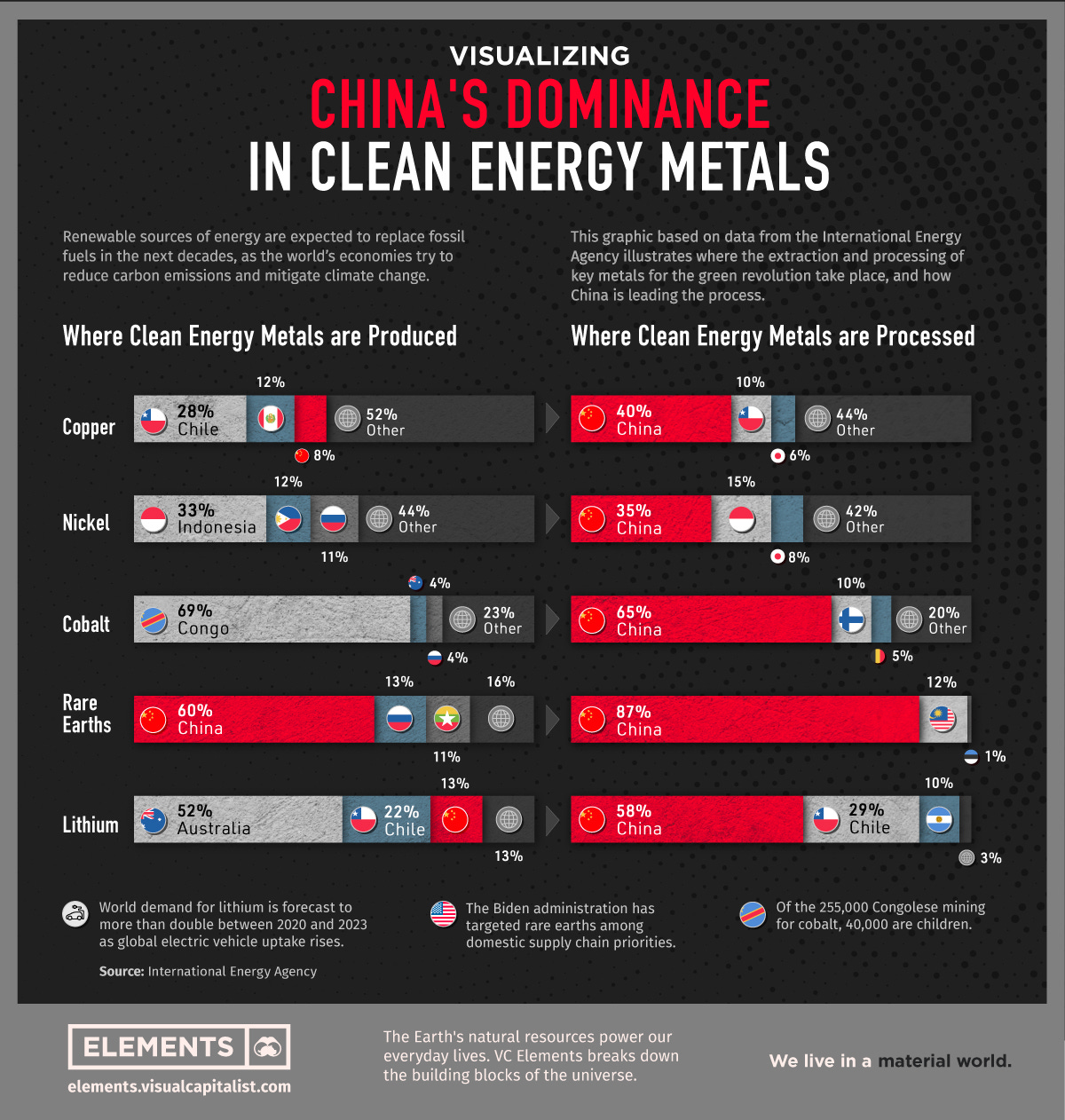

I’m sure everyone has heard by now that China dominates the supply chain for metals and minerals, whichy is why the Global North countries have been pushing the “decoupling” narrative so hard. You can see below that even China doesn’t have a lot of mining activity, it is leaps ahead of other countries in essentially all the value-added steps. More on this when I do a country profile of China but this isn’t just cheap labor driven manufacturing stuff; these are technologically advanced, sophisticated processes that aren't easy for other countries looking to enter the space (e.g. the US) to replicate.

What do these images say about the possibility and impacts of isolating China?

The second key geopolitical question is about mineral reserves. If demand for these materials is going to exponentially increase, then the question of which countries have the deposits comes before everything else.

“Six countries (Australia, Chile, DRC, China, Brazil and Russia) together hold a large share of cobalt (66%), copper (33%), lithium (84%), nickel (52%), rare earths (70%) and silver (33%) reserves.” — Manberger & Johansson (2019)

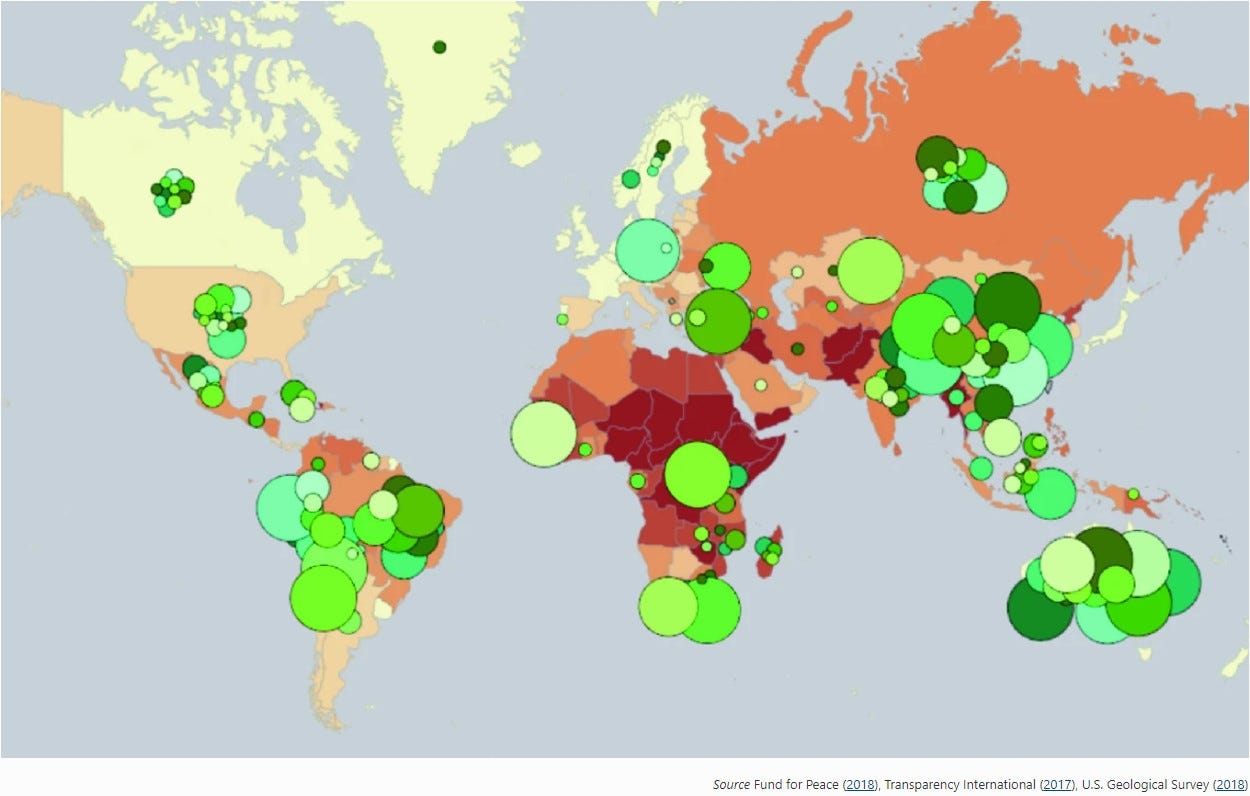

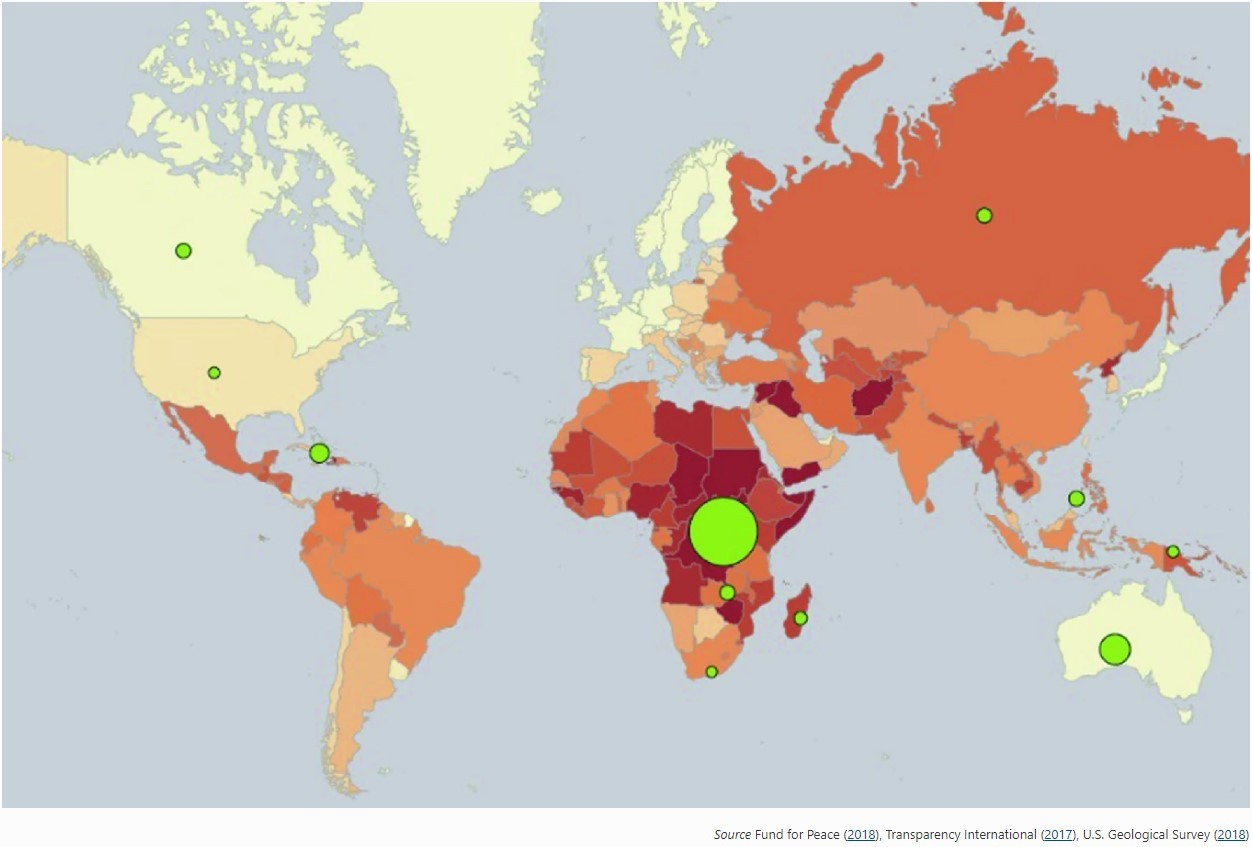

The map below shows that the deposits of these materials overlap with conflict-areas, fragile states, exploited states, etc. Areas for primary focus should be the continents of Africa and South America. For some supply chains (e.g. Cobalt, which is a key component of EV batteries), the deposits are much more concentrated, with the Democratic Republic of Congo having the lion’s share.

Map of major metal reserves (circles) overlaid on state-fragility scores (country coloring)

Map of cobalt reserves (circles) overlaid on state-fragility scores (country coloring)

There’s more to explore in this China-Global South question. In Western countries, there has been this epiphany that raw materials are important and that China has secured the supply of these through considerable investments across the African continent. The truth is somewhere in between the fear-mongering and the reality that China is in pole position.

On the one hand, China is by far the largest importer of raw materials, has most of the processing/refining capacity, etc. It has made investments in countries to secure long-term supply: for example, it owns a stake in nearly all the cobalt miners in Congo (70% of cobalt supply); it invested $4.5B in lithium projects across Mali, Zimbabwe, and Namibia; 40% of China’s copper imports come from Chinese-owned mines abroad (it consumes more copper than the rest of the world combined). 33% of Africa’s metals and ores exports go to China!

On the other, the global mining industry is much larger than we imagine. China controlled only 7% of the total value of mine production in Africa and 3% of the global share (estimate from 2019). While that definitely puts China in the lead, it is far from the position of total control that the common narrative makes it out to be.

Now let’s take a step back and look at the broader geopolitical picture, both across time and space.

One can write a whole history of our civilization, going back the past 200 years at least, as well as an analysis of the present and near future based on the maps above (as well as the maps in the oil primer). What we call development or progress is wholly dependent on material resources, which is why wars have been fought and systems have been designed to maximize access to them. It should be uncontroversial to say that from the 1700s, the search for these materials drove colonization; from the 1950s, the neocolonial system has done something similar, albeit more veiled, where the Global South has been perpetually pushed into debt traps and military conflict so that the richer nations can have easy and cheap access to these resources.

"Poor countries are not 'under-developed', they are over-exploited." —Michael Parenti

Whether in South America (Brazil, Cuba, Chile, Nicaragua, etc.) or Africa (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, etc.), democratic/revolutionary governments have tried to nationalize resources in order to develop domestic capacity for value-added processes and consumption. However, either through coups, proxy wars, of IMF-led deregulation programs, the access to cheap resources has been maintained.

Today, we are seeing the same efforts again across the world. Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Niger, Burkina Faso, etc. are just some examples of countries looking to develop local industrial capacity and challenge this status quo of one-directional development. So whether it is attempts to compete with China through investment and ownership, or through direct action (as France is weighing against its neo-colonies in sub-Saharan Africa), this will be a critical part of geopolitical dynamics going forward — even if your politics don’t recognize the historical dynamics I laid out above.

“Why does resource-rich Africa remain the poorest region of the world?” - Ibrahim Traore

III. The raw materials industry

I think it’s fair to say that this the most important industry in the world that no one has ever heard of. When we think about large oil and gas companies, almost everyone can names the likes of Shell, Exxon, Aramco, etc. But how many people can name the major commodity producers or traders — the later being the ones who get these essential materials from producers to consumers no matter the odds?

Commodity traders

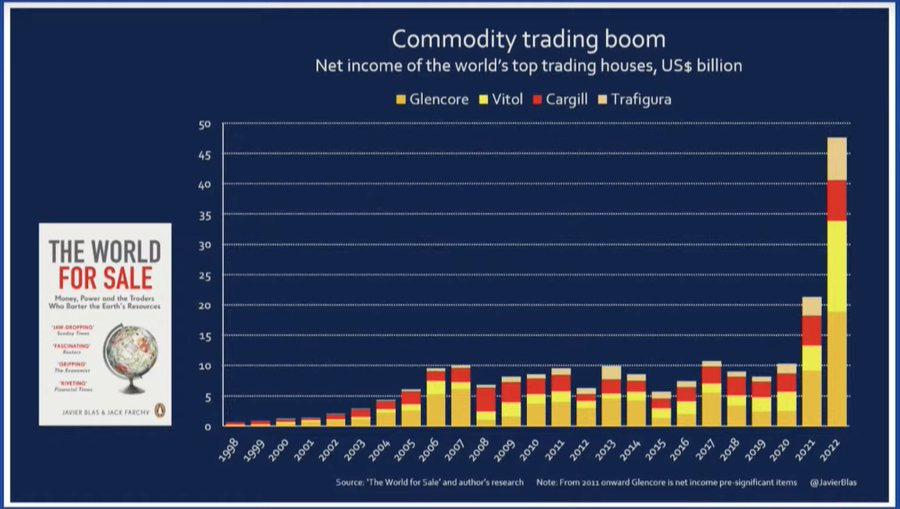

First let’s look at the trading companies. With them, it’s not just that they make pretty good money. In fact, these companies are pivotal in history shaping events by getting materials to and from some of the most dangerous places and situations on Earth, choosing sides and picking winners in the process.

For example, the commodity trading giant Vitol was able to get refined oil to Libyan rebels during the Arab Spring, helping turn the tide against Gaddafi. They also circumvented US sanctions against Cuba and sold Cuban sugar to the Soviets. Other companies like Glencore and Trafigura have worked with apartheid governments in South Africa, Saddam’s government in Iraq, and dictatorships under sanctions.

I would be willing to speculate that the continuing supply of commodities from Russia, despite the sanctions, is only possible because of these companies.

“…in their commodity deals, [their] motivation is almost always coldly financial… [However] “even if political influence isn’t their goal, that doesn’t mean that the commodity traders are not influential” — The World for Sale by Javier Blas & Jack Farchy

“The commodity traders supply the essential goods that we all rely on. The coffee you drank this morning was shipped by a commodity trader; so was the cobalt in your smartphone’s battery; so too was the gasoline in your car…

…commodity traders make the global economy tick. But they are more significant than that: Their dominance of the world’s natural resources has made them kingmakers in countries like Congo where oil or metals are the main source of wealth. They bankroll entire nations that are otherwise shut out of the financial markets, lending to them against future commodity production.” — Javier Blas & Jack Farchy

[You can read more about these stories in the book]

So who are these companies?

In the food space, a handful of companies such Cargill, Cofco, and Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM) dominate the global seed markets and agricultural commodity trading, controlling up to 50% if not more of this sector.

In the minerals and metals space, Glencore, Trafigura, Vitol, Mercuria and a few others dominate. At one point, Glencore controlled 40% of cobalt production in Congo (where 70% of cobalt production occurs). Now it has been overtaken by the Chinese state-owned company CFOB.

As with the fossil fuels industry, these companies saw a huge boom in profits following the Covid-19 supply shock.

There’s a lot more to be said on this — I highly recommend reading Javier’s and Jack’s book — but let me just cap it here by saying these large trading companies truly operate in the regulatory and financial shadows. They not only control the supply of the energy and materials that make our world possible but also influence prices, accessibility, and so on. There is no way to analyze geopolitics, the politics of where these companies are most active, decarbonization, industrial policy, energy security, etc. without understanding this space.

And lastly, this is where understanding money and global financial system becomes so important because these companies rely on funding from (shadow) banks to engage in all types of deals. The Euro$ system, how banks create money, etc. are all what enable this to happen.

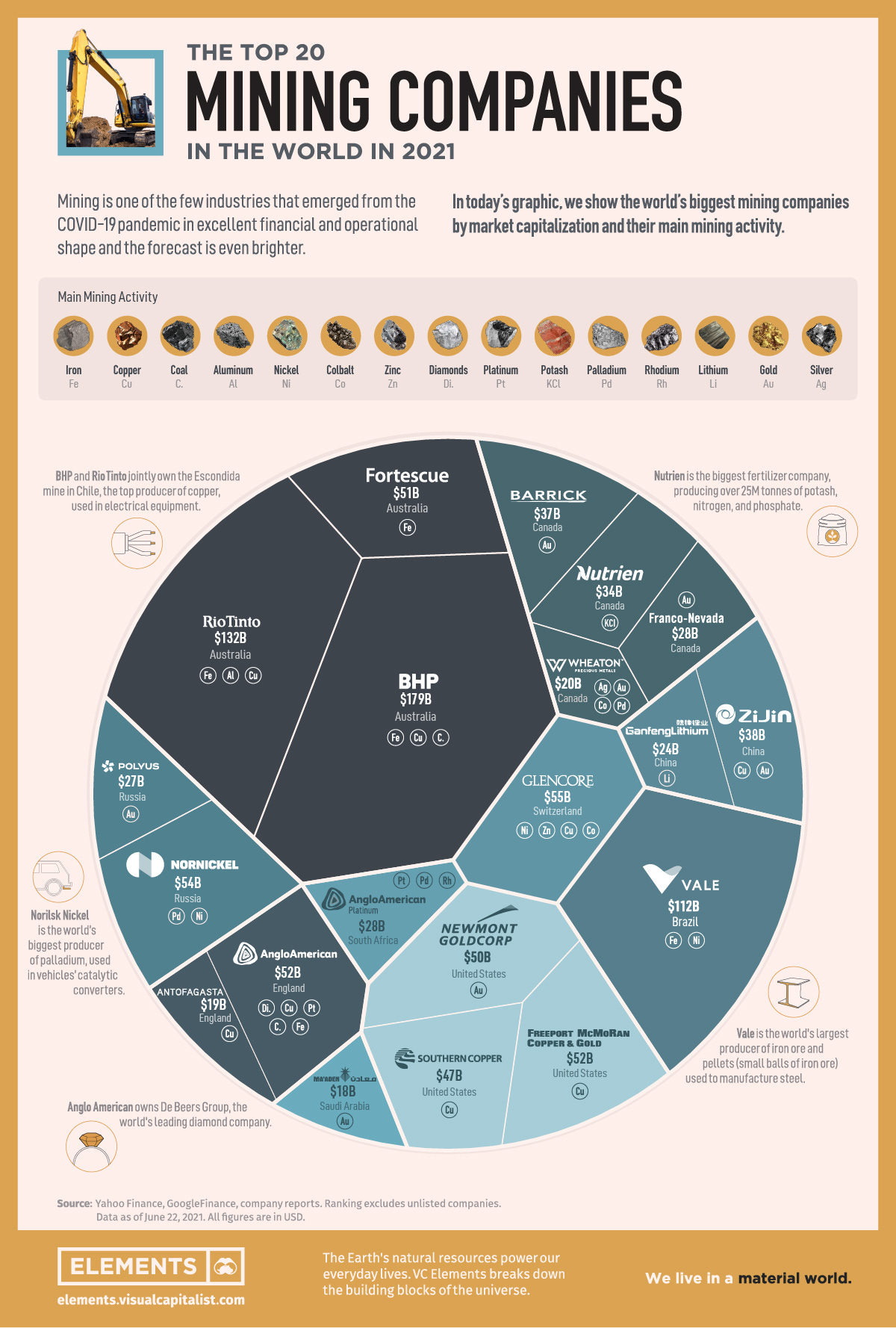

Metal miners

Now let’s look the mining part of the industry. The 3 biggest mining companies are based out of Australia but have projects all over the world. For example, Rio Tinto and BHP either own or have major stakes in copper mines in Chile, including the largest copper deposit in the world.

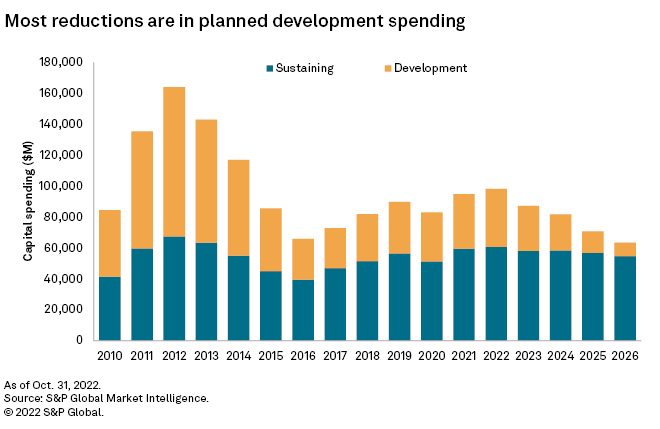

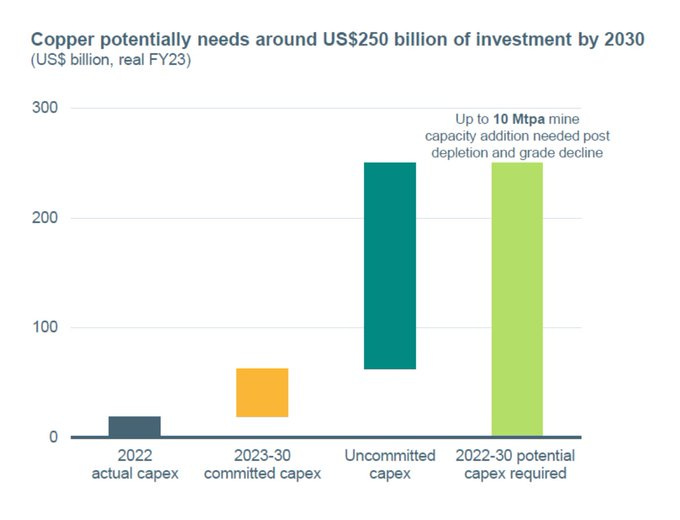

It is common knowledge by now that the energy transition requires orders of magnitudes more of these materials but miners are not yet willing to invest in more capacity. Capex investment in new developments is estimated to continue falling, even after huge profit-making years for these companies recently. Instead, the extra income is either being used to boost shareholder returns or being kept as cash on the companies’ balance sheets. Without more mining, it is hard to see how the gaping demand-supply mismatch can be closed.

Just look at ~$150B of uncommitted capex just for copper that needs to come from somewhere!

There are multiple reasons for this, some of them related to the prevailing policies and impending tradeoffs.

Mining is a long, arduous and costly process: Investing in new supply isn’t easy. The process requires various steps, including exploration, permitting, drilling, and eventually production — anywhere from 5 to 20 years. Then the mine must operate at a profit for the first 5-10 years in order to recover the initial investment. While recently higher commodity prices have helped miners make huge profits, the prior decade of low prices has left little incentive for them to invest in new, long-term supply.

ESG: There’s no question that mining is an ecologically “dirty” business, especially as deeper deposits need to be accessed. Therefore, ESG standards put pressure on miners and increase the risk to their investments, which again reduces their incentive. This is a real tradeoff — how much dirty mining are we willing to accept to achieve our “clean” energy plans?

Permitting: For various reasons, including the ESG one, permitting has become a highly bureaucratic and tedious process that can end up taking years.

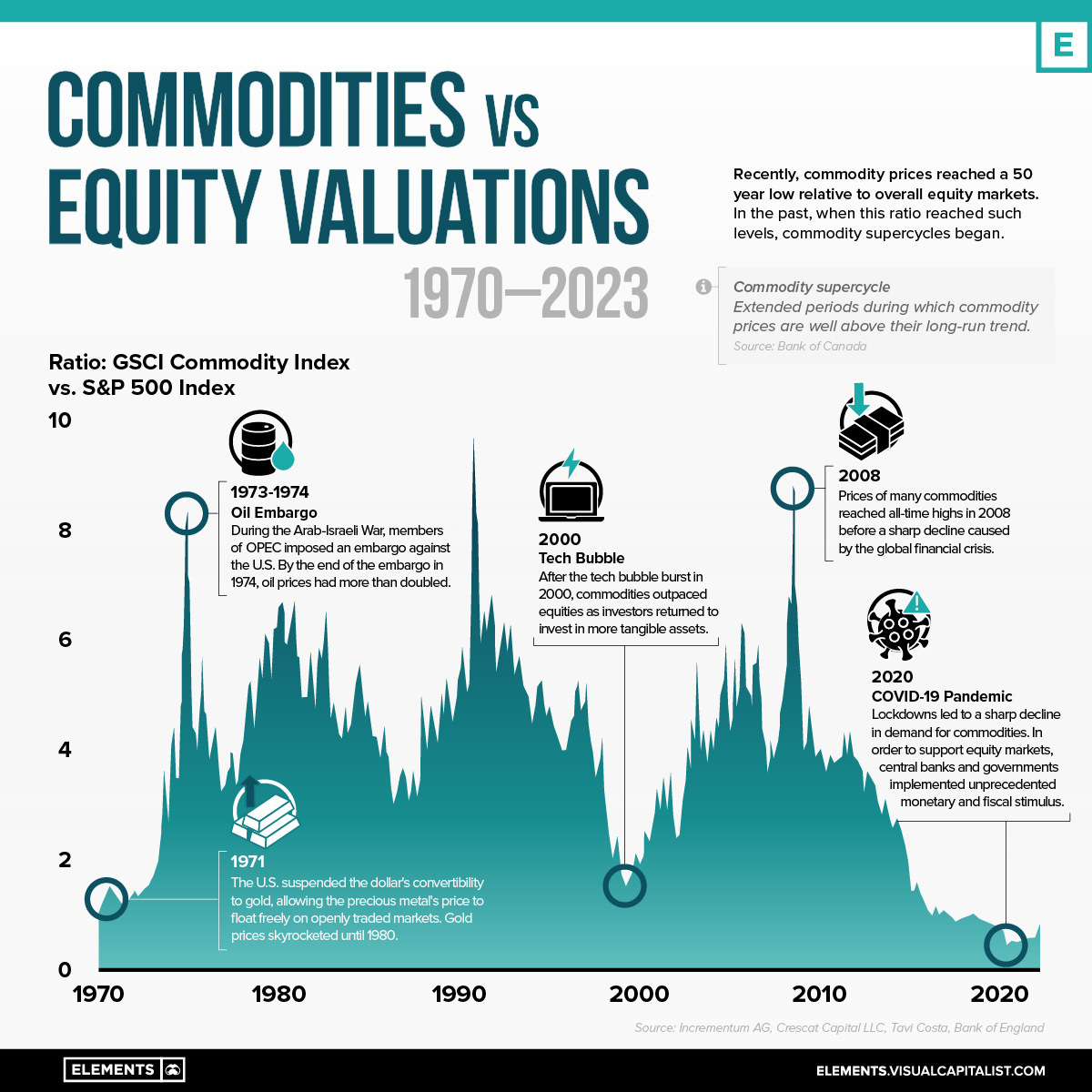

Ultimately, miners are currently in the sweet spot. They know that exponentially increasing demand is around the corner, if not already here. If they don’t increase supply, the price of commodities will go up, and so will their profits because = their are no substitutes to these materials.

This is also why industrial policy, for better or for worse, has become so mainstream now. Governments realize that, regardless of their reason, they need access to more materials. Hence, they are throwing a handful of carrots at this space (and the whole supply chain in general) to de-risk private investments.

From an investment perspective, this could be an important dynamic to understand. Many in the finance space, from Zoltan Pozsar to Jeff Currie (outgoing Goldman Sachs commodities research head), have been calling for a commodity supercycle. And from a equity valuation perspective — these stocks are at their cheapest level relative to the broader market in 50 years — coupled with the demand-supply gap explained in this piece, the risk-reward does look favorable.

Why this matters

With this piece, I have covered all three parts of what I think constitute the base layer of civilization: energy, raw materials, and money. The three topics have considerable overlap and are in some ways inextricably interconnected to create the foundational network — an invisible layer — for everything around us today.

Regardless of political affiliation, everyone is encountering an undeniable feeling that the winds of change are picking up speed. Any analysis of what is happening, what might happen, what should happen is, in my opinion, severely handicapped without understanding the forces that truly makes the essential cogs of our system work.

Our current civilization requires exponentially increasing amount of cheap and easily accesible materials and energy, a functioning monetary infrastructure which most parties trust, and geopolitical stability in order to maintain global supply chains. All technological progress, all political ideals of freedom and democracy, are built on top of this.

At the same time, this same civilization also develops, and at this point grants luxuries to, some at the direct cost of others, veiled by the illusion that everyone can have it all, while being increasingly whacked on the head by ecological constraints.

Thanks for the book recommendation on commodities, looks very interesting.