#5: Getting our monetary system right

An explainer on how governments & banks create money, what causes Global South debt crises, and what mainstream Econ gets wrong.

[Author’s note: This piece covers a lot of concepts and their applications so I hope you will find it insightful even if it’s a little long. Throughout the piece I intergated examples from mainstream narratives and explain what they get wrong.

Also, based on your feedback, I wanted to share two things:

I think keeping the length at ~2500-3000 words is the right way forward because I want these pieces to be comprehensive and worth your time. Feedback on how to improve readability is very welcome!

While I try to find the balance between keeping these pieces simple and not repeating concepts people already know, I want this to be helpful agnostic of your background on the topic. So please ask away if you have any questions at all (or have critiques) — comment here, send me an email, Twitter DM, etc. I might also open the subscriber chat option on Substack (not sure how it works yet) if it makes it easier for you to ask/comment.

Lastly, please share with your networks to help grow the community and thank you for your support in getting this far!]

Introduction

We’ve all seen the headlines:

Taxpayer money is being wasted; our future generations will be burdened with exorbitant national debt; the US is borrowing from China.

These ideas cut across the political aisle — they’re incredibly prevalent because they seem to make intuitive sense.

Well, in this piece we’ll debunk the erroneous understanding of money that such analyses depend on.

Let’s start with some of the most important money-related news in the past few weeks:

Starbucks is “debasing” its own currency (Starbucks points) by requiring 1.5-2x more points for the same items. Are these points money? How can Starbucks reduce the value of your money by 30-50% just like that?

At the recent World Economic Forum, the Saudi Minister of Finance opened the door to accepting non-US$ currencies for oil exports. This follows a recent visit of Xi Jinping to Saudi Arabia. Remember, the agreement to price global commodities, particularly oil, is critical to the US$ dominance (petrodollar)

The US is once again embroiled in a debate on raising it’s debt ceiling. As most commentators have started to admit, this is self-created farce and is not grounded in any economic reality, as this piece should hopefully help elucidate. (Mint the coin!)

In this piece, I will use the concepts explained in Newsletter #4 to describe the monetary system that exists today – everything from US$ as a reserve currency (and the Yuan threat), banking, national debt, Global South debt crises, etc.

Reminder that these concepts have implications on everything ranging from climate finance and reparations, poverty allevation, and international security to social movements and the future of capitalism.

[I mentioned previously that I wrote a long, 3-part essay on this topic over the summer. If you want a more detailed read on specific topics, I’d encourage a read of those.

Part 1: Is Bitcoin an inflation hedge? How do we define inflation? Is it a monetary phenomenon?

Part 2: How is money created? What is the money supply & how can we measure it? Is Bitcoin money?

Part 3: History of money, capitalism, Global South crises, alternative use-cases for Bitcoin]

What is money?

Thus far, we know that:

🎯Money is debt —> whoever issues it incurs a liability and whoever receives it gets an asset of the same size

🎯Money is endogenous —> it is created as a part of economic activity by relevant entities; it doesn’t just exist externally

🎯Money is sociopolitical —> it is a representation of social relations and a function of power/authority. Anything can be money.

🎯Money exists in a hierarchy —> there are multiples things called money that operate in different contexts

🎯Money matters —> it is not just important to have money; it also matters what money you have, how much control you have over the monetary system, etc.

How is money created in our system today?

Now let’s jump into the specifics of what we have today and understand, given the framework in the previous piece, where money comes from. Here it is important to give a disclaimer that my explanation will be Global North centric since they’re the ones who run and utilize the current system fully – I will explain the Global South specifics at the end.

The hierarchy of money today consists broadly of three main buckets:

Real money

Bank reserves

Money-like instruments

In this piece I will mostly focus on the first two because the third is a label that encapsulates a lot of details and financial nuances, so that requires a piece on its own.

1. Real money

This is the form of money that we use on a daily basis to buy and sell stuff, take out loans, save, etc. There are two sources of this money: the government and banks.

Governments:

In newsletter #4 I explained how governments are the ultimate source of money since they have the political power to regulate the system.

Why is government issued money the main type of money we use? It’s because the law grants it legal tender status (i.e. all taxes, fines, etc. have to be paid using that money).

How do governments create money? By spending!

It spends on a whole host of things, including employing public servants, running the military, social services, and the whole shebang. Every time it does this, it is simply paying by using its IOU: writing on a piece of paper (or in today’s world, through keystrokes on a computer). That spending becomes a liability for the government and an asset for the private sector receiver.

Does it need to check its vault to see if it has enough money? Of course not. Nothing is stopping the government from issuing as many IOUs as it wants. Remember, new IOUs get created every time, it’s not like the issuer (in this case the government) keeps its own IOUs stored in a vault. This is how every time there is a crisis, governments always seem to have money to throw at the problem, despite renowned economists perpetually warning that the next time a crisis happens governments won’t be able to respond.

Here’s a clip of former US Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan dispelling the “US can’t make its social security payments and pay off its debt” myth (something people like Elon Musk frequently fearmonger about nowadays).

A retort here might be that the money printing power of the government is not ground-breaking news, the problem is that is causes inflation. To avoid digressing into the nuances of inflation (which I cover here), its worth noting that the Global North has struggled to achieve even its inflation target despite decades of money printing. Plus, measuring the money supply is complicated, as I explain later.

[It’s because mainstream economists think money is an exogenous, finite thing.]

At this point you should wonder what’s up with taxation then. Well, taxation is about two things: firstly, its about power. Governments tax because they can as the sovereign, and since they tax in the currency issued by them, that ensures that everyone ends up using that currency. Secondly, it’s a way regulate economic activity either to avoid overheating the economy or to incentivize/disincentivize certain sectors (e.g. tax breaks for education versus taxes on tobacco).

💡There’s no such thing as taxpayer money. The government provides the people with money, not vice versa.

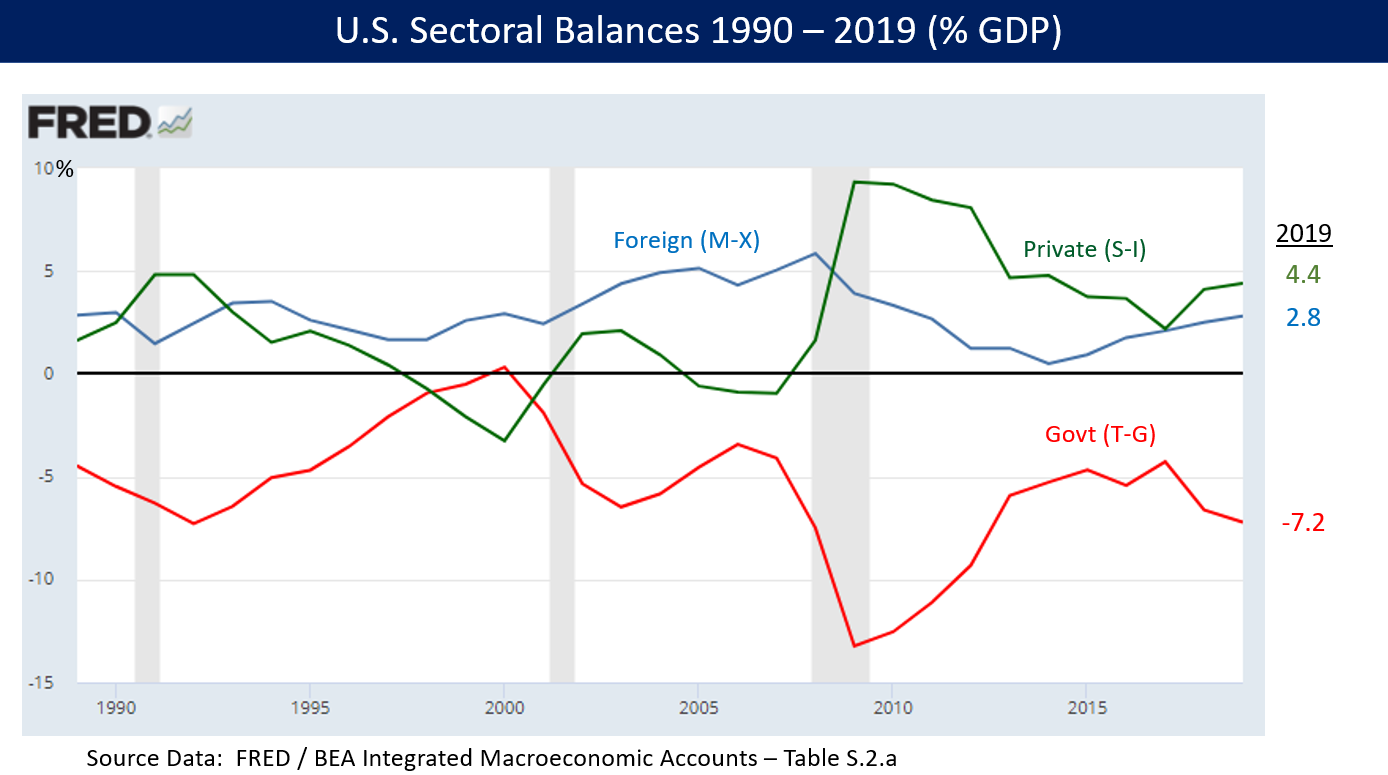

This is basically why, in many cases, governments don’t have (or even can’t have) balanced budgets. When the government spends, it injects money into the private sector (the economy) and when it taxes it takes that money away.

If taxes exceed spending for too long, the private sector (meaning firms and individuals) can end up with more liabilities than assets – basically in debt – and that’s what creates the conditions for financial crises.

Is injecting money always beneficial? Of course not. That’s not the argument here. The point of this is to create an accurate framework of how the balance sheets of the government and private sector interact. The mainstream economics notion of governments and private sector fighting over limited money (called the crowding out effect) is false.

[This refers to governments borrowing in their own currency, not the way Global South countries borrow]

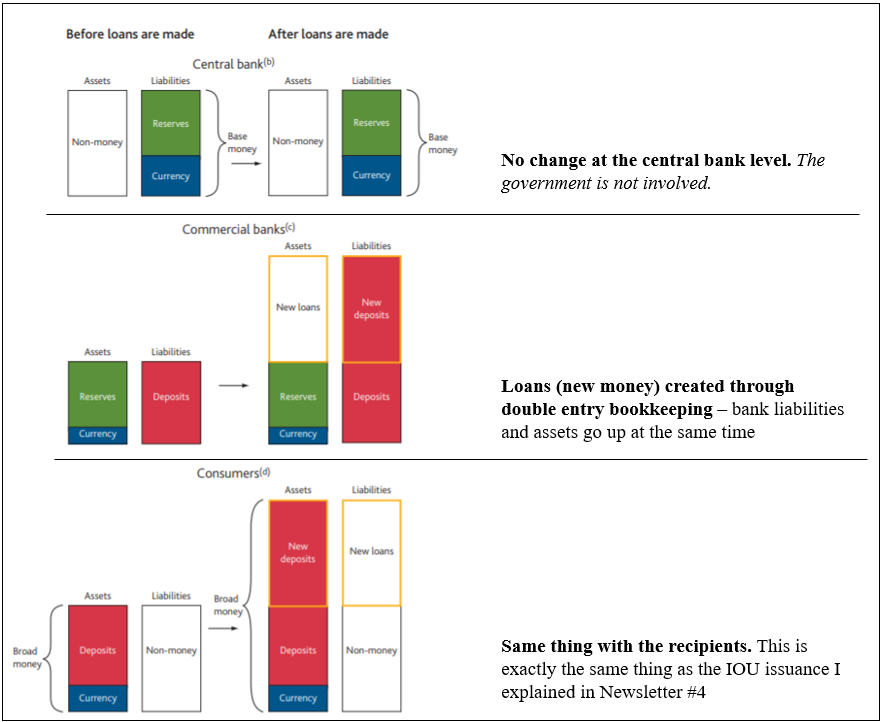

Last point here is that note the language I used about spending. This is important because it is the fiscal authority (the ministry of finance or equivalent) that creates money, not the central banks! In the US example, Congress is responsible for passing spending bills that then get executed by the Treasury. It is not the central banks that create money!

This gets clearer as I explain banking and reserves next.

Banks:

Now let’s look at banks. These are unique firms unlike most other entities because they require special charters and are integrated within the government’s payment system. This is because, especially in the current system, banks have been extended the power of money creation by the government.

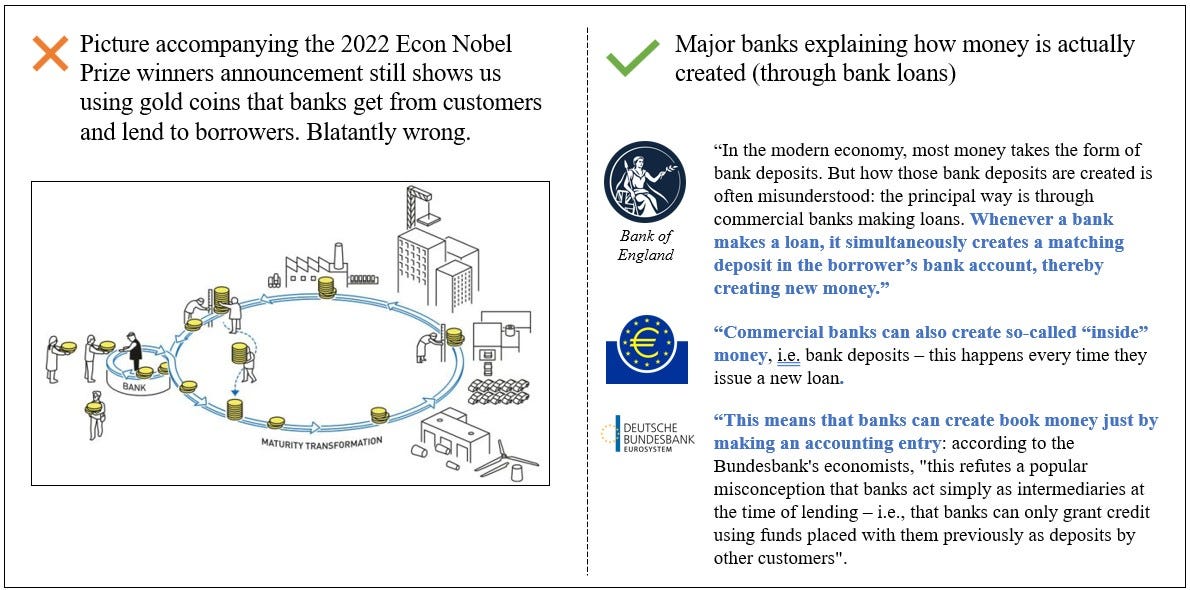

💡Yes, that’s right. Banks don’t take money from savers and give it to borrowers – they create money by lending it out! I’ll be intentionally provocative (although wholly accurate) here by saying that mainstream Econ, including last year’s Econ Nobel Prize winners, have this totally wrong.

It's exactly the same concept as above. You go to the bank and ask for a $100 loan. The bank assesses your plan, thinks about whether it can make money of it (it’s a business so it needs to make money), and if approved, increase your bank account balance by $100 through keystrokes. That bank deposit you received is just your asset and the banks liability, that’s it.

Again, there’s no vault the bank is checking to see whether it has enough money to lend. If demand for loans is there, and if banks think those are good investment opportunities, they create money (by issuing IOUs) and lend it out. There are of course regulations about how banks can lend out (e.g. can’t just lend out money to itself, must meet capital requirements, etc.) but these don’t limit how much the bank can create/lend.

k. This isn’t some fringe theory, this is a fact]

So to recap, banking is not about taking money from savers and channeling it to borrowers, it is about assessing lending opportunities and then creating money to do so. In fact, more than 90% of the money in economies is created by banks (in this way), which is what makes this fact so critical.

It is not the government alone deciding how much money there is in the economy, it is also the banks (and the shadow banks and so on).

Money creation is, to repeat, endogenous to the system such that it is driven by economic conditions and activity. The notion of some person or entity sitting with their thumb on a money printing deciding the money supply is a myth. It is a web of public and private agents engaging in a perpetual and complex network of transactions that gives you the money supply.

💡Within banking, the biggest global source of money (US$) is the Eurodollar system. This is a private, unregulated, and opaque network of global banks that create and lend US$ outside the jurisdiction of the US government.

So for example, when China needed US$ funding to fund its mega-investment projects and finance its growth, it was the Eurodollar system that created that money. This network ties together multiple non-US entities (China, Japan, Brazil, banks, infrastructure firms, etc.) in a financial web with the US$ at its base.

[Some details for those interested but you can choose to skip if you want:

There is an academic debate about whether this process of banks creating money is an extension of government power or not. Remember, anyone can create money, the point is to get it accepted (Minsky). Any bank can issue an IOU, and in fact, in the 1800s the US had a system various banks issued their own forms of money which had their own exchange rates within the local economy. Today, however, you don’t think about whether your $100 in Chase are worth less than $100 in Citibank. This is because of multiple reasons, such as the fact that all commercial banks use the national payment system to transact with each other and are hence regulated. The US govt also insures up to $250,000 of customer deposits.

The flip side of this is FTX. The cryptocurrency issued by FTX (FTT) are essentially IOUs. Within certain financial realms, you could use FTT as collateral to borrow against. Some market agents could also have chosen to accept FTT as money. But this was outside the state’s protection, so when FTX went bust, its currency went bust too. Something like this happening to a commercial bank is unlikely because, one could argue, the state extends its money creation powers to these banks and hence protects them from such risks]

2. Bank reserves:

This is a special form of money that is only issued by the government and is only used by banks to transact amongst themselves. So for example, when I send $100 from my account in Chase Bank to someone with an account in Citibank, my assets in Chase go down by $100, the other person’s assets in Citibank go up by a $100, and Chase send Citibank $100 worth of bank reserves to make this happen.

Bank reserves are important to understand for multiple reasons:

☛ Again, it is a myth that banks need a certain amount of reserves in order to be able to lend real money. In fact, banks can easily borrow reserves from the Central Bank whenever they wants.

☛ 💡When we hear in the news that the central bank is injecting XX billion or trillion dollars into the banking sector (think quantitative easing), it is injecting reserves, not real money! Reserves don’t make it into the real economy, we don’t use them to transact or anything. Those billions or trillions end up sitting on bank balance sheets doing nothing (Japan is a great example of this). It’s something to think about next you come across some headline with a crazy number of the US Fed or some other central bank is “injecting”.

[💡Fun fact: quantitative easing has been in the news for over a decade about how its an unprecedented level of “money printing”. However, QE is merely an asset swap. The central bank is buying bonds from the private sector and paying them in reserves - swapping bonds for reserves. No money is printed.

Again, look at Japan’s two decades of QE below. Japan has also chronically failed as achieving even 1-2% of inflation, even in the current inflationary crisis]

☛ Banks use reserves to buy government bonds. When the government spends, it issues reserves to the bank which then issues real money to the end recipient. Then governments issue bonds so that banks can use those zero-interest yielding reserves to buy government bonds that, in most cases, have a positive yield.

3. Money-like instruments:

The only thing I’ll say about these for now is that these are certain financial instruments such as government bonds (particularly US govt bonds) that have an almost risk-free convertibility to cash. Hence, they can be used as “money” but that too only within the financial sector. They are also the collateral on top of which the whole financial system (including lending) is essentially built. These are the most dependent on trust because they are in effect not actual money so belief in that convertibility promise is essential.

Government vs bank money

A small, simplified note about the difference between these two sources. Banks are profit-making businesses and thus cannot be in a situation where they have negative equity (liabilities exceed assets). Government’s, however, can be in a situation of negative equity (national debt) without the threat of bankruptcy. This is why governments are lenders of last resort while banks, despite extraordinary freedom for flexiblity and creativity in the current system, suffer from periodic crises.

This is also why government debt is not the same thing as private debt — the latter is much more odious.

Nuances for the Global South

The main concept here is that of monetary sovereignty, which has four main criteria:

💡Global South countries cannot fully make use of this government money creation power because they don’t have monetary sovereignty — i.e. their money isn’t very useful. Most of these countries import food, energy, critical infrastructure, etc. — all of which is denominated in US$.

Let’s use the example of Pakistan to illustrate this. The country is currency in its umpteenth debt crisis, but this time it’s perhaps more serious than ever. Food inflation is skyrocketing, core industry is suffering/shutting down, and poverty will likely rise.

Now imagine that Pakistan did not have to import all this critical stuff. It could launch a large, government funded program for regenerative agriculture, as an example. Employ the large group of unemployed people, help the environment, spur growth. It could pay the labor in PKR and procure the inputs (or at least most of them, especially energy) in PKR. This would improve food security, potentially improve exports, and would not lead to currency depreciation.

In the current system, however, such a program would require more energy, machinery, raw material imports which would require US$. The labor who would receive the PKR would also increase their overall consumption, which would also require US$ as the country would import more food, energy, cars, phones, etc. Hence, right now, any improvement in domestic consumption worsens the debt crisis.

[Even countries like China and Germany achieve their huge trade surpluses by suppressing domestic demand so that the growth of their middle class doesn’t lead to increasing imports.]

Therefore, the fact that Global South governments can’t print money the way developed economies can is not because there is a flaw in the theory (as many people assume), it’s the result of poor economic management.

Analyses that compare debt to GDP ratios in general, without distinguishing between the type of debt, are grossly misleading.

[Countries like Japan can have a debt-to-GDP ratio of >200% while Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Argentina are suffering at <100%. It’s about the currency of the debt.]

Why this matters

The most important thing to reiterate is that this is how the system works; it is not a subjective comment about how it should work or any political ideology. If we want to understand the global economy and its implications, we need to understand how money really works.

Let me do a rapid-fire below about implications for key topics:

The correct way to think about money is in terms of interlocking balance sheets: one entity’s asset is another’s liability. As money is debt, all money is created by these balance sheets. You cannot look at one sector in isolation (e.g. govt debt) or prescribe unilateral action without accouting for the knock-on effects. This applies both within countries and between countries.

[You can see below how this plays out. Interestingly, in the late 1990s when Bill Clinton pushed the US govt to achieve a balanced budget, the private sector was forced into debt. Remember, govt debt is safer than private debt because the former is the sole issuer of money]

We don’t know the money supply (MS): the whole “inflation is caused by money printing” narrative rests on the assumption that we know what the MS is. But given the endogeneity and hierarchy of money, it is thus far impossible to accurately measure how much money is created or destroyed across the global banking sector, shadow banking, the Eurodollar system, and money-markets (where money-like instruments are prevalent).

So for people who use the M2 money supply metric to explain the stock market, inflation, etc., please stop. That’s like trying to estimate the amount of water in a bucket by only look at one pipe and ignoring any holes + other sources.

“The problem is that we cannot extract from our statistical database what is true money conceptually, either in the transactions mode or the store-of-value mode.” - Alan Greenspan (former US Fed chair), 2000.

Money doesn’t have inherent value and is not a measurement tool: For the past few years, too many people have been talking about the debasement of currency and how money has lost 90% of its value over time. That is a meaningless metric and analysis.

Money is not like inches such that it needs to stay stable over time. There is no natural rate of money growth or money stock — what matters is how many real resources consumers can afford and their welfare.

The growth in inequality is a policy, control over the means of production, and economic ideology problem, not a money supply one.

[If you spend enough time on Twitter/Reddit, you’ve probably come across this chart and how “government debasement of currency” is causing the rampant inequality we face today. While the inequality part is a fact, this chart below shows and means nothing.]

Source: Visual Capitalist Countries like the US don’t borrow from China (or Japan etc.): This is one of those perpetual myths that academics, politicians, and commentators keep regurgitating (e.g. Obama). Here’s a very recent clip from a popular MSNBC host repeating this myth.

All they have to do is to stop and ask themselves why the US, which is the sole issuer of US$, would be borrowing its own currency from other countries? The reason these countries hold so many US bonds is because they have large trade surpluses, and rather than keep US$ they buy interest bearing US bonds. They need the US bonds because its the safest form of collateral globally, rather than the US needing US$ form them.

The national debt (in the national currency) does not have to be paid back: If you follow the logic from this newsletter and the previous, then you know that the national debt is simply a stock of the money injected by the government into economy. What does paying it back mean? Taking money from the private sector and paying the government. Why do that? The govt issues the money. Paying it back just destroys money (remember IOUs being cancelled when returned to the issuer).

The next time you see commentators take the national debt and divide it by the population to come up with some absurd figure about how each citizen is indebted, tell them they don’t know what they’re talking about.

The government is not a household, you can’t apply the same logic!

“This assertion [that governments must act like households] makes about as much sense as claiming that the earth is flat because we can see the ground in front of us is level” - Dean Baker

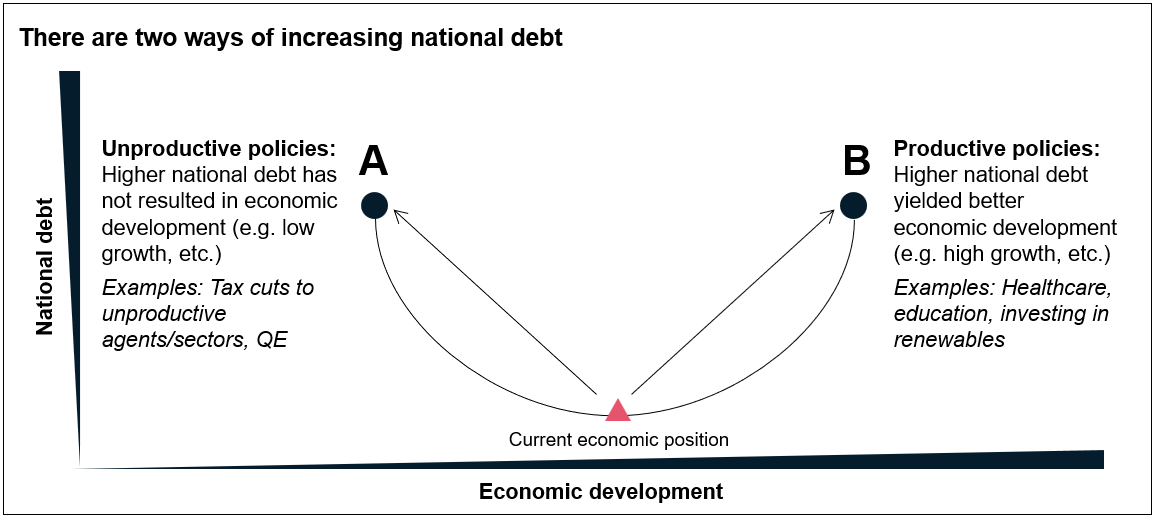

This doesn’t mean that all increases in national debt are good. While I won’t get into the second/third order impacts here, the point is that the government should use its power to improve productivity and welfare, rather than subsidizing and bailing out the rich.

De-dollarization & deglobalization will be painful: There’s been a lot of chatter about these topics recently. I mentioned this in newsletter #1, the celebrity financial commentator Zoltan Pozsar just wrote about in the Financial Times, and news about Russia/China/India/Brazil looking to use gold or the Yuan for international trade come out every week.

While the signs are there — geopolitical fracturing, US trying to onshore industry, etc. — the fact is that all countries are tied together because of interlocking balance sheets. Political experts miss this point, especially those that love to divide the world between liberal democracies and others.

As of now, all countries are incredibly co-dependent because a complex and all-encompassing global system has been built on top of the US$ (btw, this doesn’t help the US per se — more on this later).

Is any other country willing to open up its balance sheet in a way that it supplies a new global reserve currency? Is any other country willing to have huge trade deficits in order to supply its currency globally? Understanding money as a balance sheet creation allows such insights.

Hence, these two forces — an entrenched system at the base vs. geopolitical fracturing — will continue together and antagonistically.

Resources

David Andolfatto - Money Supply (in-depth explanation of money)

Great one Taimur.

I didnt quite understand this "There are of course regulations about how banks can lend out (e.g. can’t just lend out money to itself, must meet capital requirements, etc.) but these don’t limit how much the bank can create/lend.

The whole reserve multiplier thing that we are taught about how banks take our deposits and then lend out 90% of them and so on is a myth. Money creation is endogenous. "

My understanding is that Central Bank require bank statements from banks and penalise bamks that go beyond certain thresholds of lending. Hence controling the amount of money banks create...

Hello Taimur, thanks for this article. Super new to finance and found this to be a fascinating read!

One question I have is about the government debasement of currency chart. Why is the chart meaningless? Why is it that it used to cost $1 to buy a 30 Hershey's bars but now you can't? Or that it used to cost .99 for a gallon of gas and now that's not the case? Isn't that inflation? And that's what Bitcoin is protecting against. It certainly feels like prices are rising and in all of history, prices have never decreased for any significant amount of time (in the Global North).