#7: Is everything happening all at once - review of 2023 (thus far)

Analyzing the discourse around the US dollar's demise, the increasing China-Russia-Saudi alliance, and other major events related to finance, energy, and geopolitics.

Author’s note: This is a short(er) piece that brings together recent newsworthy events within the framework I have been using in the newsletter.

Be sure to check out the 3 potential risks to look out for over the next few months.

As always, thank you for the continued support — if you like this piece or learnt something from it, please share across your networks.

Follow me on Twitter (for less curated takes and more shitposting!)

___

Key topics covered: US dollar dominance; China-Saudi; BRICS; oil; IPCC.

Introduction

When I wrote the pitch for this newsletter, I quoted Lenin’s infamous line:

“There are decades where nothing happens. And there are weeks where decades happen”.

That has been the driving motivation behind this publication, and I suspect you’d agree with me that a lot has been happening recently. It’s not just the changes but the speed, intensity, and complexity with which it all seems to be unfolding.

So with this piece, I want to take stock of what have been the most significant developments over the past few months. This is, of course, by no means exhaustive but provides a commentary on some of the events we have likely been hearing about more frequently.

In newsletter #1, I presented a framework that had 3 pillars that explain the base layer of our civilization:

Energy & raw materials

Macroeconomics & finance

Geopolitics.

Let’s look at the biggest events across each of them.

Macroeconomics & finance

In the winter, I was in Pakistan and there were murmurs about the possibility of a financial crisis. People were worried about liquidity risks and bank failures. While Pakistan remains in a precarious situation, it is weirdly ironic, and perhaps even more worrying, that the two main bank failures have been in highly prosperous places: California, with Silicon Valley Bank, and Switzerland, with Credit Suisse.

There’s sufficient good commentary and debate on why these failures happened so I won’t get into that (Nathan Tankus is the person to read on this), but it’s the policy response that is more interesting. The US government promised to protect all deposits in US banks (while the current legal limit protects only $250,000 per account), although there has been some confusion between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury about what the actual design of this is.

This has brought up a lot of interesting questions about the nature of banking: if private banks need government backstopping, is banking truly a private industry? Or are banks basically performing a public good by creating money through loans on behalf of the government?

This excellent write up in the Financial Times provides an answer that I agree with – and explained in newsletter #5.

The second response was that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) extended dollar swap lines to its key allies: Canada, England, Japan, the EU, and Switzerland. To recap, the US$ is the global reserve currency meaning that every country and private entity, for the most part, needs US$ to transact. In times of financial stress, such as a (perceived) banking crisis, the financial instrument everyone needs to inject liquidity and stabilize the market is the US$. A swap line is simply a direct way for the central banks of countries to borrow US$ directly from the Fed and quell financial risks. There’s a financial implication here, which is that the use of swap lines is evidence for systemic risk in the global financial system, and a geopolitical implication that although every country needs US$, only a handful get privilege access to it.

Swap lines are as much about economic conditions as about national security.

The countries not lucky enough for this access do have some recourse. The Fed has a separate facility where foreign central banks can borrow US$ - but that is up to a limit and with stricter terms. This is typically one of the last options for these countries. It is worrying then that an undisclosed central bank, rumored to be Turkey, maxed out the use of this facility by borrowing $60B a few weeks ago.

More signs of brewing global distress.

End of the US dollar?

Simultaneously, however, there is also a lot of kerfuffle about the US$ replacing its global reserve currency status. Note, this arrangement is the linchpin of the global system so this would be no small wave in the ocean. The leader of this revolt seems to be China, with other major countries like India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kenya, etc. also joining the bandwagon.

There are two hypotheses out there:

China wants the Yuan to replace the US$

The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) want a more multi-faceted currency system for global finance.

Here are some recent news stories about it:

Brazil & China opening up a Yuan settlement channel for trade

India settling trade with Malaysia & Tanzania in Indian Rupee

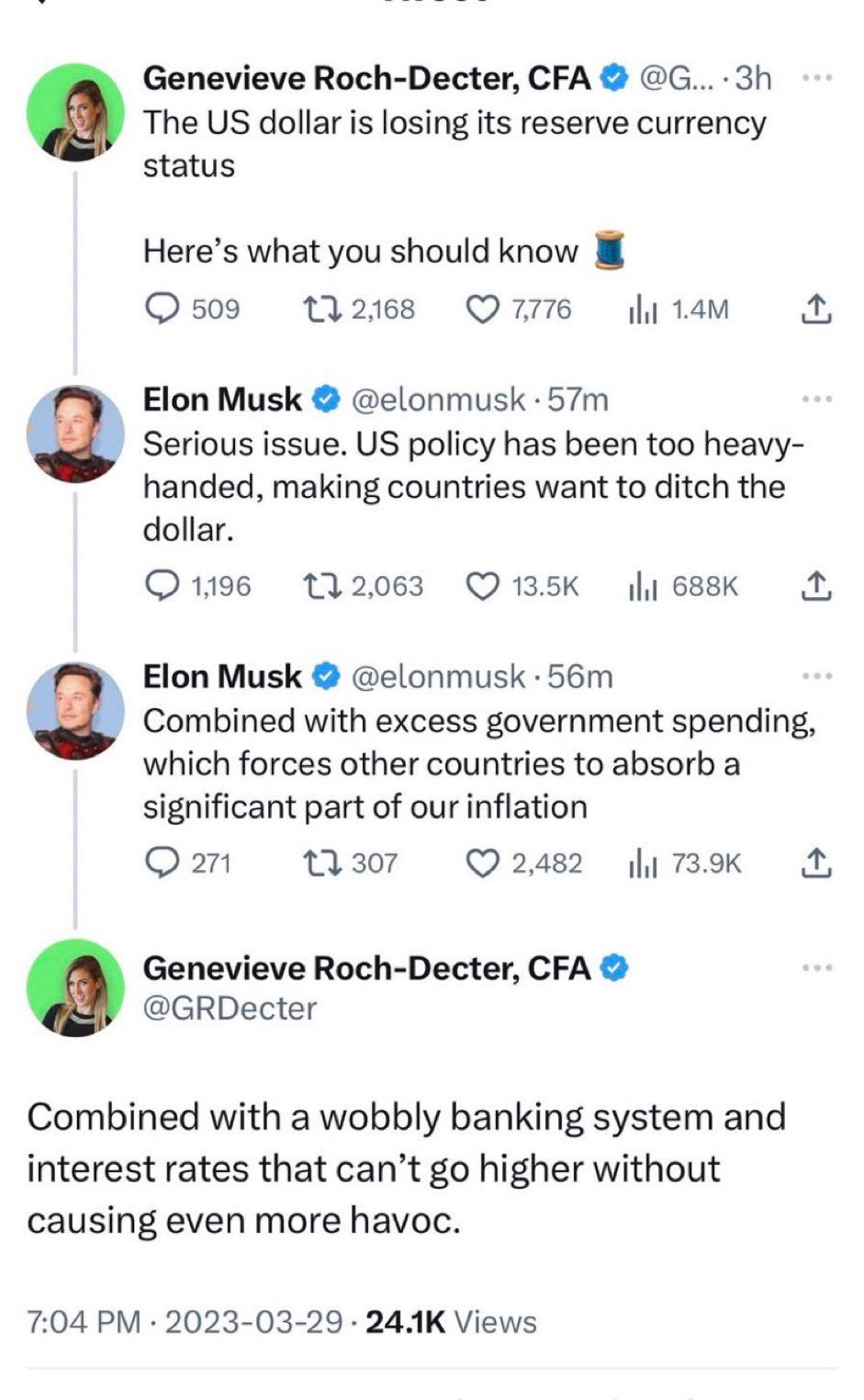

Based on all this, fear-mongering about the US$’s demise is running full steam ahead across the political spectrum:

Except, we have been here before many times.

Analyzing this is a tough balancing act because, as I wrote in newsletter #1, I do think de-dollarization is on the horizon. This isn’t particularly surprising — nothing lasts forver. However, I don’t think it is going to happen soon or smoothly, and that many of the above analyses represent stark misunderstandings about money and finance.

[Heuristic: the majority is always wrong].

My base case is that countries will continue to push around the edges but it will mostly be for show because of three reasons:

1. The plumbing of the global financial system is built around the US$ (swap lines, global payment systems, etc.). It’s a little like shifting the HVAC system for a building from individual ACs and heaters for each room to a central system. The scale and complexity of the task at the hand, particularly within the structural confines of the global system in terms of trade, geopolitics, etc., is almost impossible without significant disruptions.

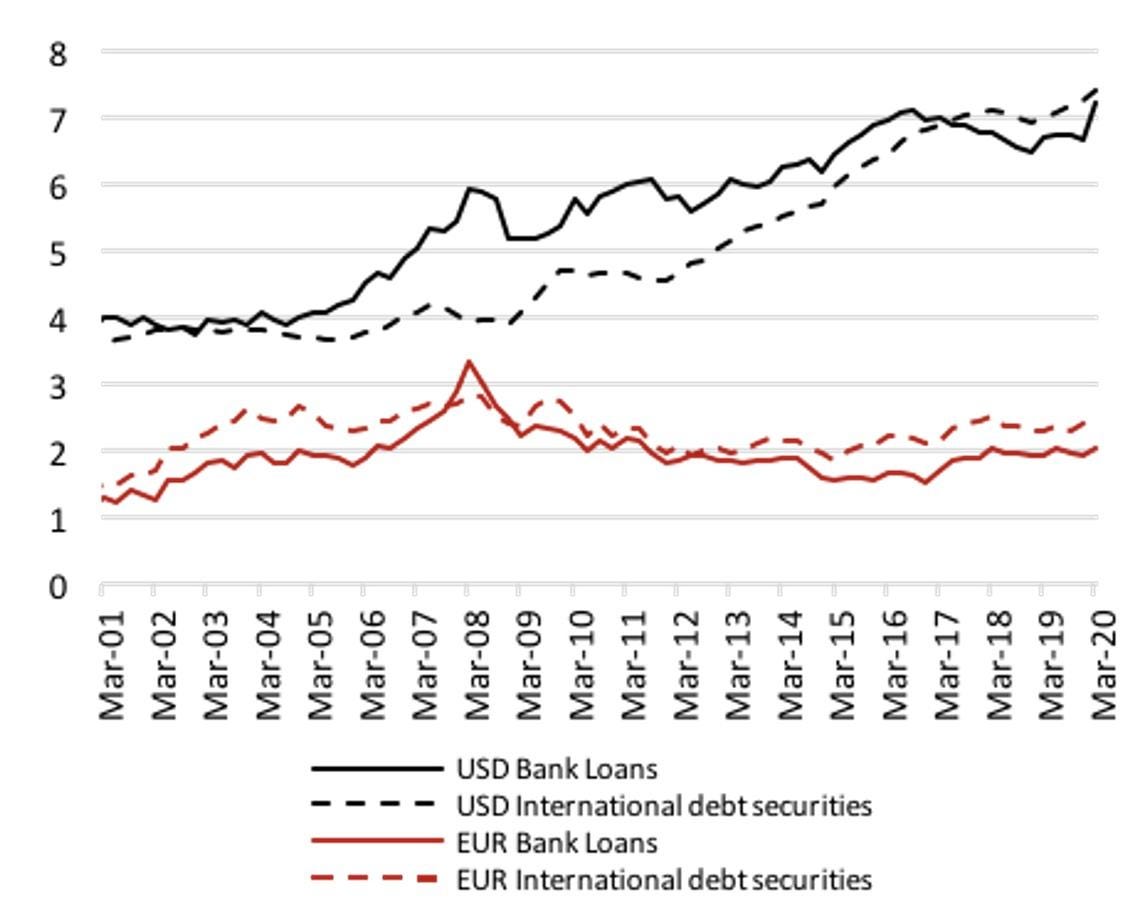

2. The world has major liabilities and debt denominated in US$. Whether it is private companies ranging from raw material importers in Nigeria to multinational shipping firms, or governments and state-owned enterprises, everyone has significant liabilities denominated in US$. Unless there some wholesale wiping of the slate clean – a debt jubilee maybe – these agents will need to get US$ somehow to clean their balance sheets.

Figure 1: International foreign currency debt of non-banks as % of global GDP

3. Being the global reserve currency (GRC) is a tough life. This particularly true when people talk about China wanting the Yuan to takeover. I don’t think there is any evidence of that desire since being the GRC isn’t simply about what currency global trade is denominated it, it’s about opening up your national financial system for the rest of the world to use. For example, the US$ has its position because the US is open to huge financial inflows from the rest of the world. Agents get their hands on US$ and then use it to buy US assets (bonds, stocks, real estate, etc.). This makes the circle whole. China on the other hand runs a very closed financial system tightly controlled by the state.

Just simply take China’s example here. For many years there’s been this myth that China holds a certain power over the US because it own’s so many US bonds, and that it has been selling them recently which is a sign of the latter’s weakness. Well, not quite. US assets reign supreme, which is why China is selling US bonds but buying US agencies (mortgage-backed securities).

Remember, the US is not borrowing from China; it is China who relies on US assets being available so that it can park the money it earns from its trade surplus.

To conclude this section, I think a lot of this dollar death dance is just another example how so many commentators just don’t understand how the financial system works. It almost doesn’t matter whether Saudi Arabia sells oil to China denominated in Yuan because Saudi Arabia is likely going to convert those Yuan into US$ to buy US assets or use those US$ to trade with someone else who needs US$ to pay off their liabilities.

The dollar system will, like all those systems before it, die. But it will be messy, painful, and chaotic. The US$ will die of strength, not weakness, because everything else around it will suffer first – such is the nature of the system.

Energy & raw materials

I wrote recently about how oil is in many ways making a comeback, mostly in terms of spotlight because it’s importance to the system never dwindled. Biden going ahead with approving the mega drilling project in Alaska, on the back of faster oil drilling permit approvals than Trump, along with his Energy Secretary talking about how the reduction in oil dependence will take decades, just offers a pungent reality check.

Fossil fuel dependence is not withering; in fact, it is reclaiming geostrategic importance. Take the recent news about Japan buying oil from Russia at above the price cap imposed as part of the sanctions. Japan is a staunch ally of the US and the West, not particularly known for bold moves against the grain. And yet, it is also highly dependent on energy imports.

Similarly, India has been beating the same drum for months, talking openly about how it has no reason to not make use of cheap fossil resources from Russia to serve its own domestic needs. As I wrote in the last piece, Europe has also been doing the same, merely buying Russian resources through intermediaries like Turkey and Saudi Arabia – can’t let reality get in the way of political handwaving.

Needs before narratives.

China, as the largest oil consumer and importer in the world, is also making big moves. It recently signed a major deal with Saudi Aramco to build a refinery. Such moves are essential in delinking these countries, in materials terms and not just vague commitments, from the Global North.

In terms of the raw materials, the impending criticality of metals and mineral such as copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel, and so on in order to meet decarbonization needs has been in the news for a while. Producers such as Indonesia, Chile, and Brazil have thus been talking about forming an OPEC style cartel to gain market power and not simply be exploited for cheap resources. The dynamics of oil are quite different than these materials; nonetheless, OPEC has yielded significant political power over the decades and so a new cartel would also have major implications of supply chains, military conflict, trade, etc.

Lastly, Chad recently announced it is nationalizing the oil sector, taking over the resource extraction operations that have thus far been run by Exxon. Although it isn’t a major oil producer, the development is emblematic of what we might see going forward for the aforementioned reasons.

Useful to remember how nationalizations of critical sectors such as energy and agriculture in the second half of the 20th century was a core driver of regime change, overthrow of democracies, and military interventions in the Global South by the Global North.

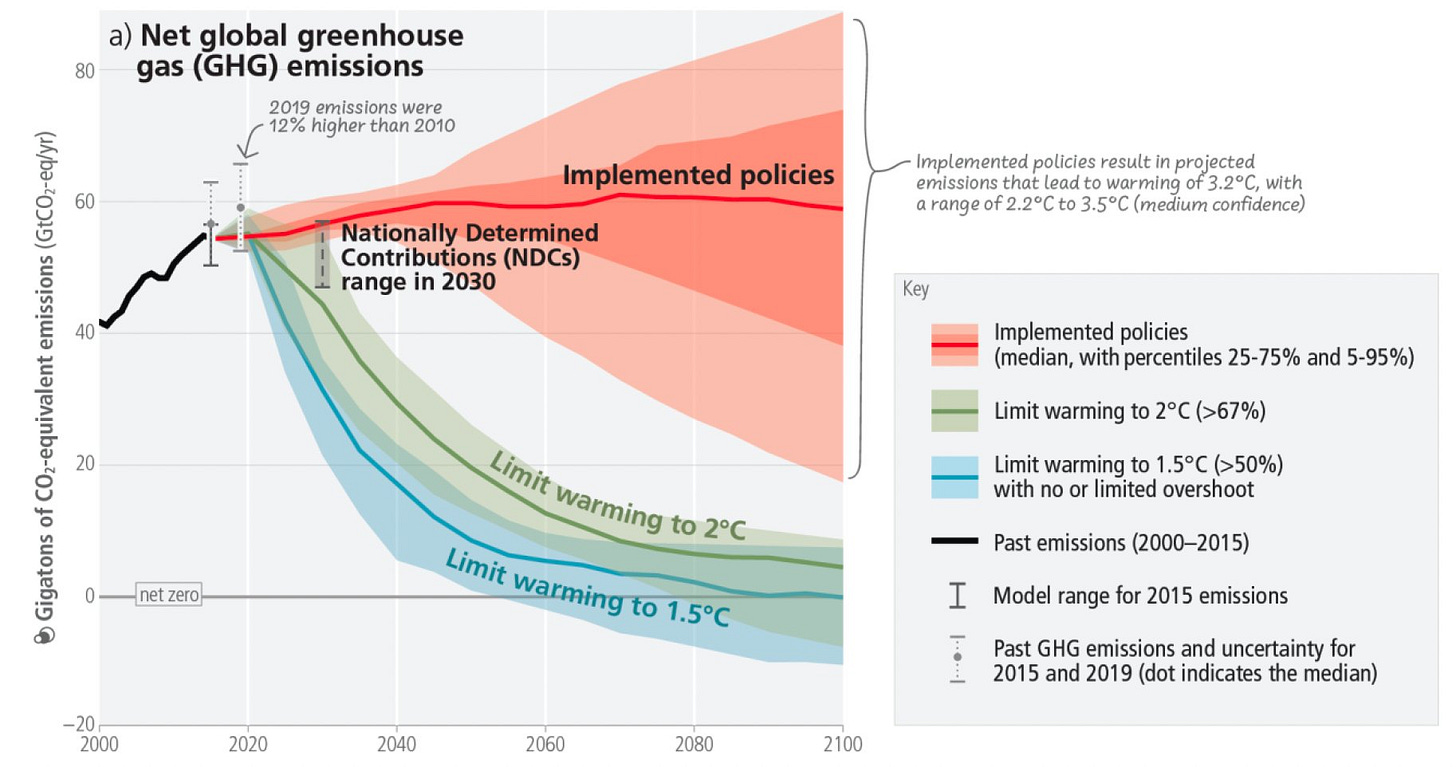

In the backdrop of all this, the new IPCC report just dropped and it doesn’t look good.

Here’s a great thread on how the report is watered down because of politicians:

Geopolitics

This angle is already deeply embedded in the topics above but let me present three quick developments that I think warrant attention:

China’s increasing global mediation: The news of China brokering a deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran is massive for many reasons. China’s ability to exert influence in the Middle East, a key geostrategic area for the US, to the extent that it brought KSA and Iran, who have been engaged in decades of proxy wars, together is impressive.

More Global South integration is on the horizon: There has been news that Saudi Arabia, Egypt, UAE, Argentina, Mexico, and Nigeria have all requested to join the BRICS cohort. These are major regional players and such coordination would challenge not just the current unipolar system, but also reduce chances of a bi-polar one in favor of regionalization.

The Global South is speaking up: More on the narrative side, the past year has seen multiple instances of countries not falling in line to the whims of the Global North. Leaders from Brazil, India, Malaysia, and South Africa have not complied with the anti-Russian demands of the West, reminiscent of the Non-Aligned Movement of the 20th century.

Lastly, although not directly geopolitical. I would say that looking at brewing domestic uproar in countries is critical to watch because of the spillover effects. The massive protests in France, even by French standards, the chaos in Pakistan, even by Pakistani standards, and the increasing politico-social violence in India are all examples of events that could structurally change the dynamic of these countries, and hence, the global networks they exist in.

What to look out for

Here’s my top 3 things to keep an eye on for the next few months:

Global economic slowdown (recession: unemployment ↑, stocks/wealth ↓, inflation sticky) driven by lower credit availability — credit drives the economy — and a weak Chinese recovery. The recent OPEC oil production cuts are a sign of this recognition. Increased risk of financial crises, particularly in the US commercial real estate sector and emerging market debt, pose major threats as well.

(Bonus: Watch the big tech stocks, Japanese bond market, and USD-HKD peg as they are pillars of global financial stability).

Global North fractures due to anti-China moves. The US might be willing to push even harder on China — the recent TikTok hearing is a good example — and may even go as far as investment bans, but places like Europe will find it much harder to decouple.

More extreme weather. This winter has already seen intense weather conditions (much more rain and storms) — the summer could be worse with the possibility of an El Nino in the US and Europe. We are already seeing unprecedented ocean heat this year. The weather is one of those few things that can light a spark in a heightened socioeconomic powder keg because it impacts energy use, food production, health, etc.

Conclusion

With so much going on, it feels overwhelming to just try to keep up, let alone make sense of everything. Polarization, media hype, and the opacity of systems can lead to either resigned acceptance, even blissful ignorance, or despair.

I think that to protect from that, it is useful to try to not miss the forest for the trees. While the latter can feel disorienting, the former can offer more digestible structures and maps, allowing some way to comprehend events.

That is the goal here. Learning how things really work, while maintaining a big picture perspective, can help come to terms with what we must live through and also be more prepared to build a better tomorrow.

Was waiting on a piece that touched on the recent yuan and BRICS issue and this delivered!! Great read.