#6: A sticky situation - our chronic oil dependence

Oil runs the world - let's understand it to move past it.

[Author’s note: Slightly longer piece but I wanted to give a thorough primer on oil because of how consequential this is going to be for our future.

Topics covered:

Where oil is consumed & what a barrel of it constitutes

The geopolitics of oil (Russia, China, etc.)

US production & self-sufficiency narrative

Fossil fuel industry subsidies & record-profits

The truth of decarbonization and risks to Global South development

Sidenote: There’s too much happening globally to integrate into these pieces but sharing two recent events that I think are highly consequential:

Anyways, eager to hear feedback and thoughts on this piece & how to achieve decarbonization + development of the Global South within this context.]

Introduction

The problem statement is simple: we need to use less fossil fuels because of ecological reasons and their declining cheap availability. Yet we live in a world where fossil fuel companies are making record profits, fossil fuel consumption is steadily increasing, and the “climate president” in the US is speeding up oil drilling.

Why?

*****

Fossil fuels have become a taboo topic over the past decade. For those worried about climate catastrophe, fossil fuels must go – and fast. As with all taboos, there’s a growing and vociferous countermovement. These aren’t necessarily climate deniers – that’s very 20th century. Instead, these folk recognize the climate problem (although with lots of caveats) but hinge their argument on the benefits of fossil fuels to human civilization. For them, the benefits outweigh the costs.

I want to provocatively say that this countermovement does have a point: we are tremendously dependent on fossil fuels. This countermovement, to which I do not subscribe at all btw, has been getting more traction recently (check out how popular Alex Epstein has gotten — he recently testified in front of the US Congress — or this speech at the Oxford Union that went viral a month ago) is because those of us who worry about the ecological crisis have not adequately acknowledged just how entrenched fossil fuels are, and how challenging and disruptive reducing their consumption is going to be.

[I explain how this countermovement is wrong at the end].

Also, even if you don’t care about the climate, it is still important to understand the role of fossil fuels because our cheap and easy access to them is declining, which has major socioeconomic and geopolitical implications.

I think a good framing for this is: “don’t hate the player, hate the game”. Making fossil fuels a dirty concept doesn’t help. They are incredible packets of energy presented to us as gifts of nature – it is our overuse, profiteering, and exploitation that has led to this crisis. The problem is the system, not the energy source.

[Note: fossil fuels companies are part of the system.]

So in this piece, I will deep-dive into the monarch of fossil fuels: oil.

As I explained in newsletter #2, our energy honeymoon is ending one way or another, which will lead to major disruptions to our way of life. But we can only adapt, prepare, and respond, both from an ecological and developmental perspective, by better understanding oil and its role today.

This is the only way to achieve a real energy transition, which hasn’t been happening thus far and is a task humanity has never taken on before.

There are three parts to understanding oil:

1- How oil contributes to everything we consume

2- It’s role in the geopolitical order

3- The political economy of the fossil fuel industry

Part 1: Oil’s role in economic activity

Oil is the driving force of modern civilization and yet its demise has been an oft-repeated claim over many decades. Just take a look at this Economist cover from 2003:

Over the past decade, the mood around oil replacements – mainly renewable energy – has been boisterous. Solar, wind and battery costs have dramatically reduced, EVs and electric bikes are becoming trendy, and there’s been a narrative shift away from dirty fuels.

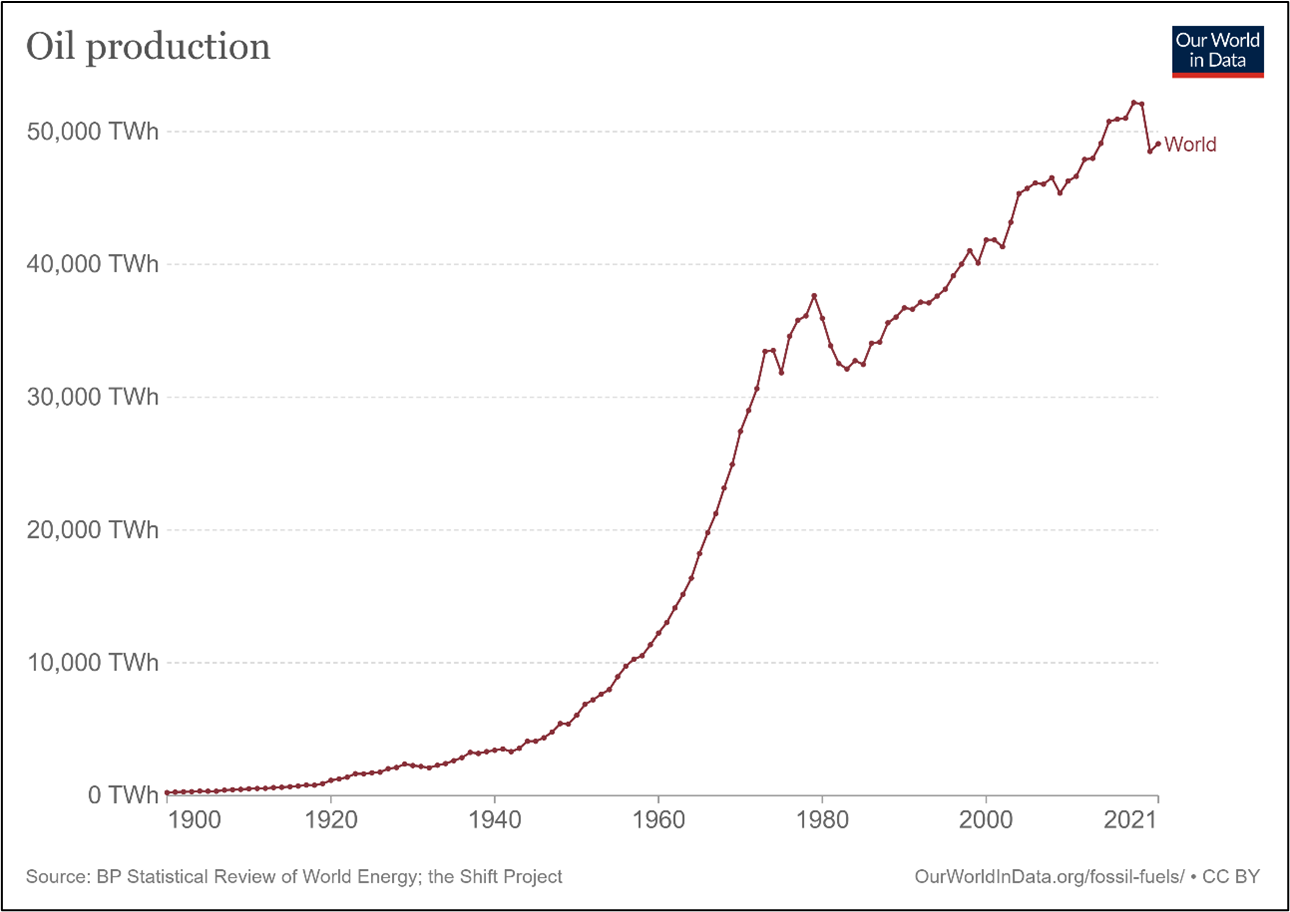

And yet, global oil production has been continuously increasing year-on-year, tightly correlated to global GDP growth. People talk about decoupling but in the terms that matter (absolute oil consumption & global), growth = oil consumption.

Figure 1: Global oil production. [Expected to rebound to all-time highs in 2022 and keep trending higher. The dips correspond to recessions.]

Conventional wisdom says that this is being driven by growth in the Global South, mainly India, China and so on. But look at the interesting case study of Norway, where oil consumption has remained flat (it has one of the highest per capita oil consumption levels globally — 3x China & 10x India) despite EVs being 90%+ of new car sales and 98% electricity coming from hydropower.

Figure 2: Norway oil consumption compared with share of EV sales.

What makes oil consumption so sticky?

The popular energy expert Vaclav Smil identifies 4 products as the foundations of modern civilization: cement, steel, plastics, and ammonia.

This is no exaggeration. If you think about anything in our life, from survival goods (e.g. food, clothing, housing) to sources of comfort and satisfaction (e.g. furniture, packaged goods, hospital equipment, transportation), they are all wholly dependent on some combination of these 4 foundations.

What is the primary ingredient in the production of these 4 essentials? Oil!

There are two ways in which oil provides value:

As a high-quality source of energy. In fact, oil sits on top of the energy pyramid given it’s the most energy dense (along with natural gas), relatively easy to transport, etc.

Source of various chemical compounds that get used in producing other materials.

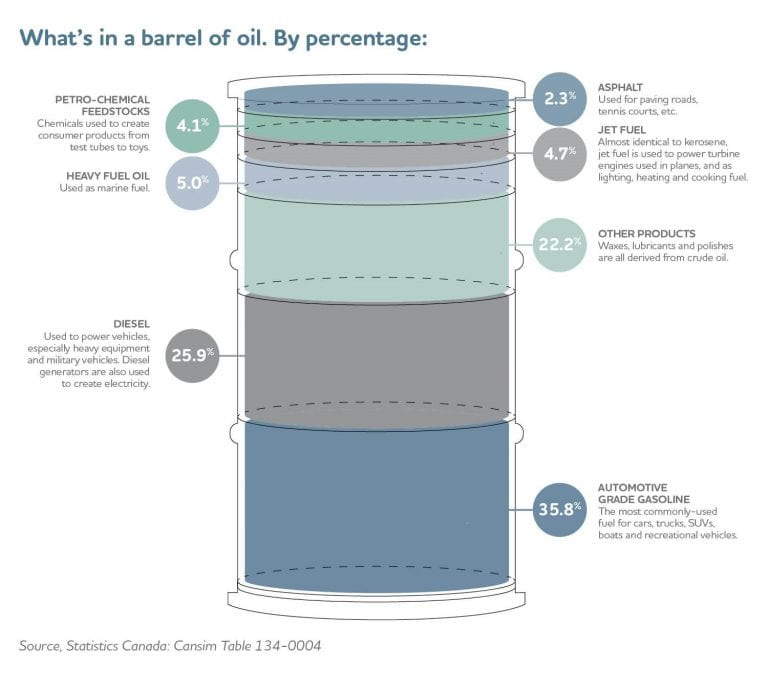

Across both of these roles, a single barrel of oil provides a surprisingly high level of output.

Add to the infographic above the following, inexhaustive list of other things oil is an essential component off: cosmetics, hospital equipment & medical instruments, pharmaceuticals (e.g. aspirin), cleaning chemicals, household furniture, and roads & pavements, etc. Just think about the quantity and variety of plastic products we use!

[Another cool visual]

Basically, almost everything around us uses oil as an ingredient. And then the value chain that is used to produce and transport everything around us uses oil as an energy source.

What exactly is oil?

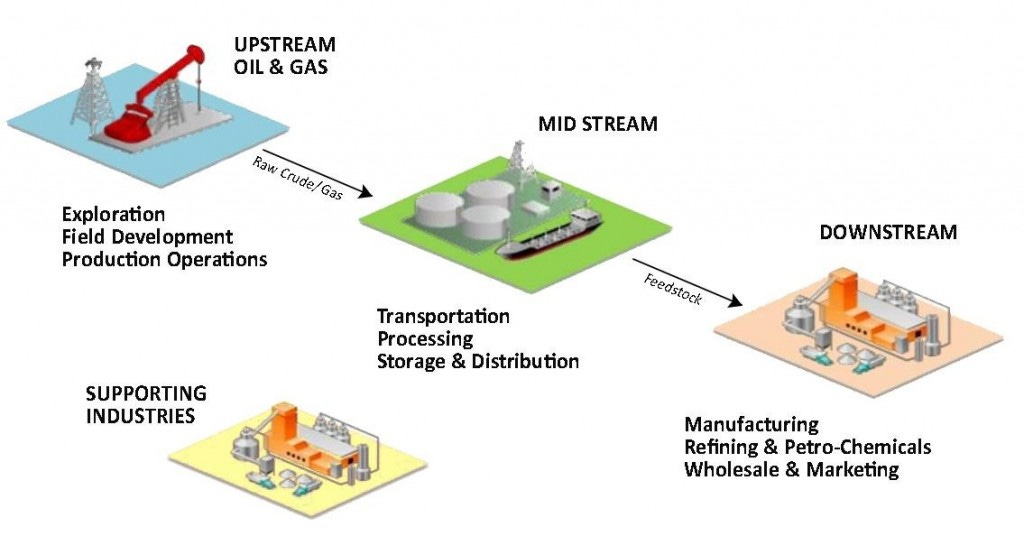

The important thing to recognize is that the term oil actually refers to a variety of things. What gets pumped of the ground is crude oil, which then goes through a refining process to give us various forms of hydrocarbons, each with its own properties and use-cases.

Here’s a quick 101 on the oil value chain, from drilling to final industrial use:

For the purpose of this explanation, let’s focus on the refining process. Essentially, this involves heating crude oil to high temperatures and separating the various liquids within it based on their different boiling points. The lighter fuels get extracted first, followed by heavier, more energy dense fuels at higher temperatures.

Let’s go down the list from light to heavy fuels:

Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs): This stuff gets distilled out first. The main NGLs are butane and propane – the former is used in small lighters, and the latter is used to heat homes & run those nice flame heaters we see in restaurants. Other NGLs like heptane are used as feedstock for the chemical industry and used to create medicines, textiles, lubricants, and many other things. I can’t state this enough: a lot of our everyday goods come from these compounds.

[Sidenote: A lot of natural gas gets produced as a co-product of oil drilling. This is important because natural gas is a core component of fertilizer production (which our food system totally depends on) and is touted as the main “transition fuel” for clean energy.]

Gasoline: Next up is gasoline, which is the major component of crude oil and what likely comes into our imagination when we think of oil. It is mostly used for various forms of transportation. When we talk about EVs, it is only this part of crude oil that is being replaced. Also, in a world where car sales are growing by 2-3%, even an increasing share of EVs does little to decrease demand – in absolute terms – for gasoline cars; at best, it can slow it down.

Diesel: Labelled as the “hemoglobin of the global economy”. We all think about it as a side product, but it actually runs the cogs of our system. Ships, trucks, heavy equipment, etc. all run on diesel. This includes all the transportation that enables global supply chains (everything from transporting materials to delivering our packages), the heavy machinery used in construction, mining and agriculture, and even backup electricity generators in many parts of the world. Think about how much (again, heavy and expensive) machinery would have to be replaced to wean off this diesel dependence.

Jet fuel/kerosene/heavy oil: Relatively smaller % of the barrel but used mostly for heavy transport like aviation and shipping, and for some heating related use-cases (kerosene). Just aviation itself is a major consumer of these oil products and is growing at 3% annually. ~100,000 flights a day consuming ~1 gallon per second each!

Paraffins/asphalt: Heavy, sludge like stuff leftover at the end that is used in paving roads, waterproofing buildings, making Vaseline, etc. Again, think about how much of these substances are needed given the rapid rate of urbanization in the Global South and the infrastructure renewal in the Global North.

All in all, we use every part of a barrel of oil because of its unique chemical properties and the effort required to extract oil from the ground. This is why growth = more oil use.

💡To close this chapter, let’s put the decarbonization effort in perspective. EVs and renewable energy may reduce the need for gasoline and heating oil, but what about everything else? Oil is already a tiny sliver of electricity generation.

For everything thing else, we still need to extract the same barrel of crude oil, still need to go through the same processes of storage, transportation, and refining, and would still be consuming a range of oil products.

Scenario 1: We keep using most of a barrel of crude oil but keep the gasoline aside (from EV displacement for example). But what do we do with it? Who stores it? Does the reduced revenue from gasoline make every other oil product more expensive?

Scenario 2: We keep extracting more oil for all its end-products and simply find an alternative use for gasoline, if it eventually does get disrupted by EVs.

Is there a 3rd scenario in a world with increasing consumption?

You can see that even in places like Europe, where renewable energy and other green efforts are the most advanced, oil product demand has been flat (note: these countries are already at consumption levels well above their fair share from a population perspective).

Figure 3: Consumption of oil products. [This includes oil products “consumed” for manufacturing, meaning that the end-product might actually be consumed elsewhere]

Part 2: Geopolitics of oil

In many ways, oil gave birth to the modern world so it’s not surprising that the geopolitics around its value chain directly impacts global security and relations.

For example, oil has been a critical component of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. For Russia, it has been a major source of revenue and leverage; for the US, it has been a pivotal target for sanctions and an impetus to improve self-sufficiency; for Europe, it has both been a key sanction target and resulted in a costly scramble to find alternatives (mostly because of natural gas though); for other major countries like China, India, Indonesia, etc. it has been a major break in the global system as they have used discounted Russian oil for domestic gain.

Figure 4: Buyers of Russian Crude Oil. [This is good evidence that Russian oil is actually circumventing global sanctions and still ending up on the global market]

Let’s take a step back and understand the dimensions that drive the geopolitics of oil. I would argue that there are three main big picture factors:

1. Producers vs consumers

One way to think about it is – similar to the framing of money in newsletters #4 and #5 – that we must of oil relationally. For every seller, there is a buyer. It’s typically thought that power is in the hands of the producers, but oil is only useful if they can sell it to earn US$, which they then use to buy other things they need. This, however, requires two key players: refiners and consumers.

Firstly, we can see how the producers of oil have evolved over the last century. While there is still considerable concentration within which countries control supply, there is greater diversification today than any other period prior. The general intuition here would be that with more global competition for supply, the power of some of the largest players (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Russia, etc.) would significantly lower. In fact, according to these charts the US is producing more oil than both Saudi Arabia and Russia. This fits in with a lot of the new narrative around US as a net-exporter and the geopolitical implications of that.

Figure 5: Change in global oil supplier’s

Figure 6: Share of oil production in 2021. [You can see how concentrated oil production is in certain geographies. How map compares to a map of refiners & consumers is the crux of oil geopolitics]

However, oil production is not the right metric for the simple reason that market power depends on net exports — domestic production minus consumption. If we look at that, it is clear how dominant Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are, respectively. All three of these countries are net exporters both of crude oil and refined products, while the US is almost neutral.

Figure 7: Comparing major oil producers in terms of next exports.

The learnings from chapter 1 are important here because distinguishing between crude oil and refined products helps understand market dynamics.

Let’s take the example of the US, particularly because the oil self-sufficiency narrative has become so prevalent. The US has ramped up domestic production through its shale oil industry (which we will get to) but most of it is light oil – a less dense form of crude oil that primarily yields gasoline and diesel. However, the refining infrastructure in the US is built to process heavy crude oil – which is denser and yields more products for petrochemicals, etc. Therefore, the US must export its light oil and import heavy crude oil; it then refines the latter and exports products. This also matters when politicians in the US consider bans on oil exports, because they don’t recognize these nuances.

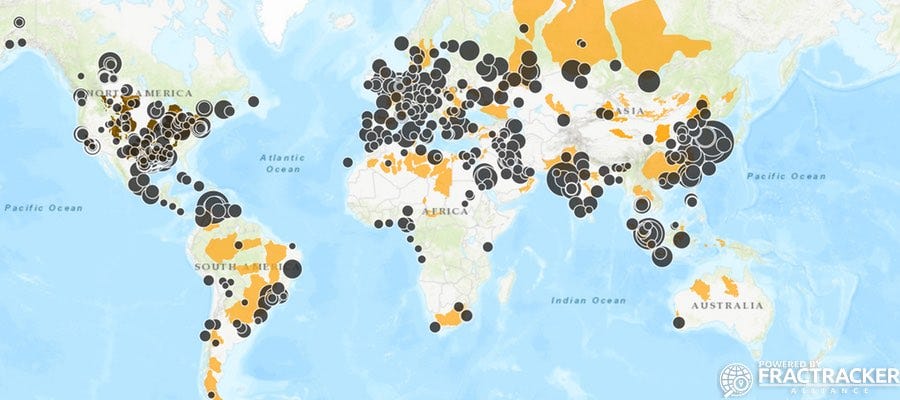

Also, brief point here about US production. For four decades since the 1970, US oil production was steadily in decline, only to reverse and dramatically increase during the 2010s. This is because of technological advances that allowed the US to access shale oil – also known as “tight oil” because this is oil present in the source rock, which is much deeper in the Earth. This is basically the final layer of rock that has oil, and hence is much more expensive and ecologically dangerous to recover. Without constant investment and new wells being drilled (since shale oil wells deplete a lot faster), this would be a short-lived spike.

Figure 8: Spike in US oil production due to shale oil/fracking

So international market power in oil depends on production in excess of consumption (that’s the exportable amount), the quality of crude oil produced, and the domestic refining capacity, since refined products have a higher premium (you can see how Nigeria is stuck in a resource trap as it exports the raw material but is unable to capture value by producing higher-margin, processed oil products).

The last interesting point to note here is China. It is a huge consumer of crude oil with domestic refining capabilities to create products that are then used in its industrial sector. This helps China be competitive in terms of manufacturing, while also making it a key wielder of market power globally. If China is not buying, sellers have a problem. This is why there’s so much news now about the Chinese reopening and what it means for oil demand, as well as whether we will see the rise of the Petroyuan – that China will pay for crude oil in the Yuan rather than the US$, a major dent to the US$’s dominant role.

The China-Iran-Saudi store is important here.

[I will address the Petroyuan debate in the next piece because I think the current mainstream chatter around it misunderstands China’s intentions]

Figure 9: Map of global oil refineries. [Interesting to see how Europe has so many refineries despite limited oil production (helps them capture economic value) and how much capacity China has built up.]

2. Transportation

Our global system depends on being able to move around oil for refining, storage, and consumption reliably and cheaply. This wields its own form of geopolitical power because disruption to supply routes can lead to major ripple effects. I briefly touched on this in newsletter #1 when I talked about how the US’ naval forces and foreign military bases are part of the effort to maintain control of supply routes.

There are two main forms of inter-country supply: onshore pipelines, and shipping.

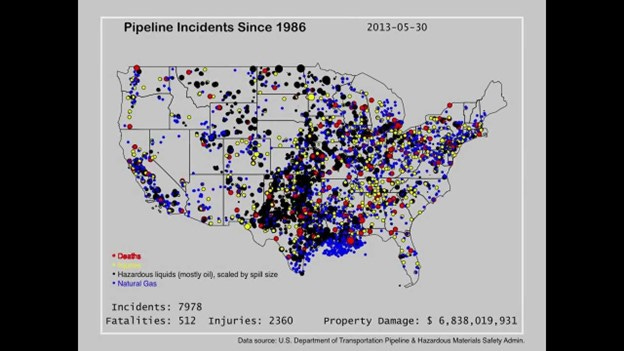

Pipelines: They are a complex web of mostly land, and some offshore, pipelines that transport oil between and across countries. Compared to natural gas though, oil pipelines are fewer because trucks and railroads are popular methods of transportation as well. It is not surprising to see that most of the pipelines are concentrated in Russia, China and the US, given their land mass and scale of production/consumption. There are some important inter-country pipelines, particularly from Russia to Europe (through Ukraine), that pose major geopolitical risks – for example, the Druzhba pipeline is one of the largest in the world and can transport ~2 million barrels/day from Russian producers to refiners in Europe.

These pipelines, however, have major ecological consequences because their construction involves dislocating local populations (often indigenous/rural communities), deforestation, severe damage to local plant and animal populations, soil damage, etc. Further ecological destruction occurs when oil leaks happen, which is unfortunately a common occurrence globally. For example, a leak in Ecuador last year polluted 21,000 of a nature reserve, poisoning the river and other resources that the local population depended on for survival. Just in the US, oil pipeline leaks have been averaging about 1 per day!

Shipping/tankers: ~60% of oil globally gets moved around by oil tankers. These are extremely large and heavy ships that are specially designed to bulk transport crude oil and refined products. Some of the larger tankers can carry ~2 million barrels of oil, which is the same amount of energy as a large nuclear weapon!

The map below highlights the importance of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea in terms of oil shipping lanes. In particular, the chokepoints at the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca represent major sites of geopolitical conflict. For example, 20% of global oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz which is located in the Persian Gulf. Who controls most of this area? Iran. This has led to multiple flashpoints between Iran-Iraq and Iran-US over the past few decades, with threats on the rise again today. Similarly, the China imports 70-80% of its oil on tankers passing through the Strait of Malacca, making it an essential geostrategic area given the scale China’s dependence on foreign oil.

Oil spills in the ocean are also a major ecological threat, killing marine life, damaging ecosystems, spilling toxic chemicals that stay in the ocean for years, etc. Not only spills, but the functioning of these mega-machines also harms marine animals and the ecology through the release of large amounts of wastewater, bilge water (a mixture of oil and water), collisions with animals, etc.

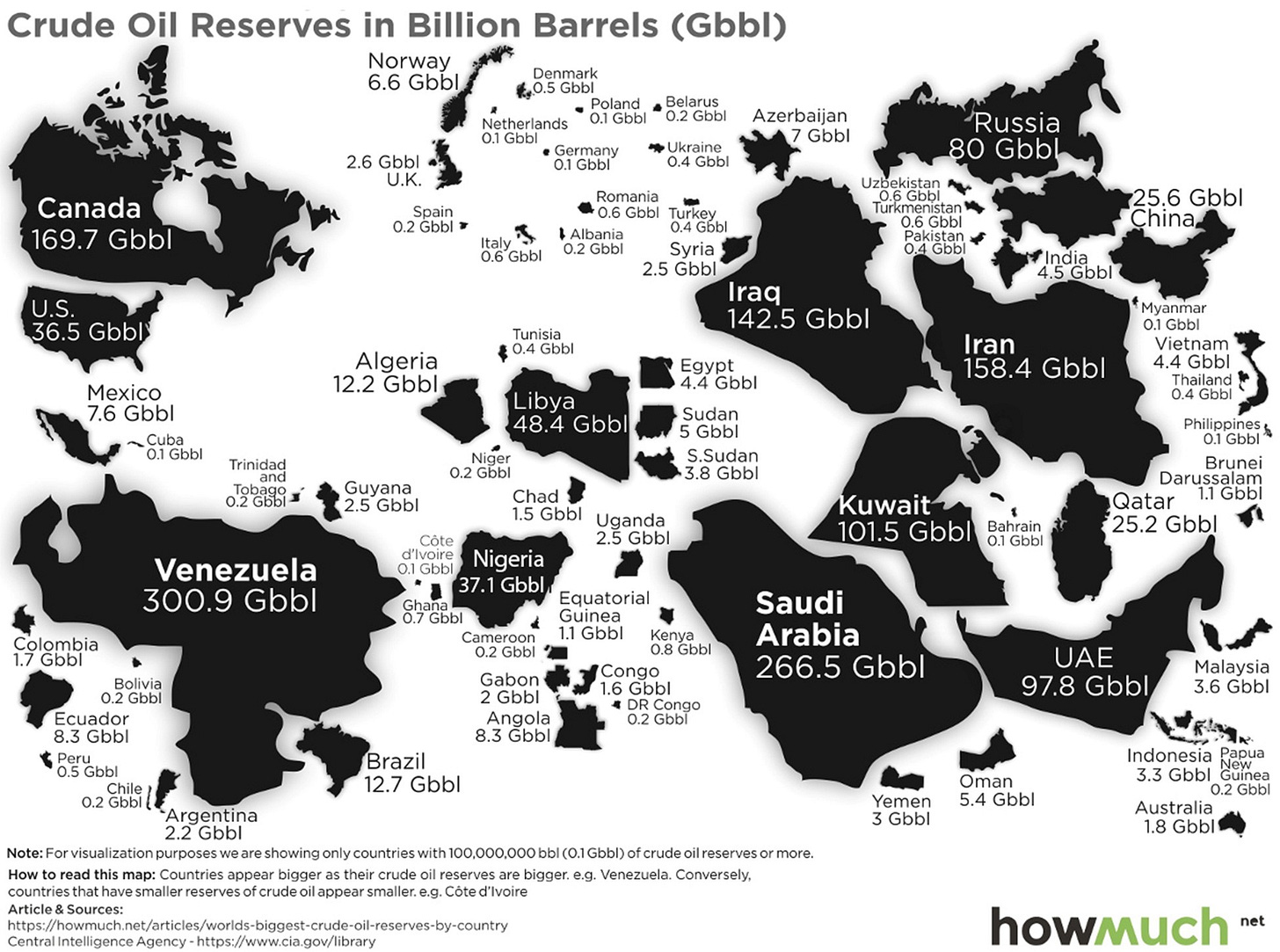

3. Oil reserves

To be brief, the race for more oil reserves is definitely full steam ahead. Countries recognize the importance of securing access to oil, and with production in certain regions becoming less economically viable (e.g. potentially fracking in the US), onshore and offshore regions with large reserves are going to be critical.

In terms of land, this will lead to a continuation of the inextricable relation between oil and foreign intervention, whether militarily (think the US in Iraq) or through the global economic system that carves open the resources of less-developed without enabling them to even refine and export higher-value products.

[Note: oil reserves refer to the quantity of oil that is accessible given current technology and oil prices – reserves may increase if oil prices go up, meaning companies can invest more in extraction]

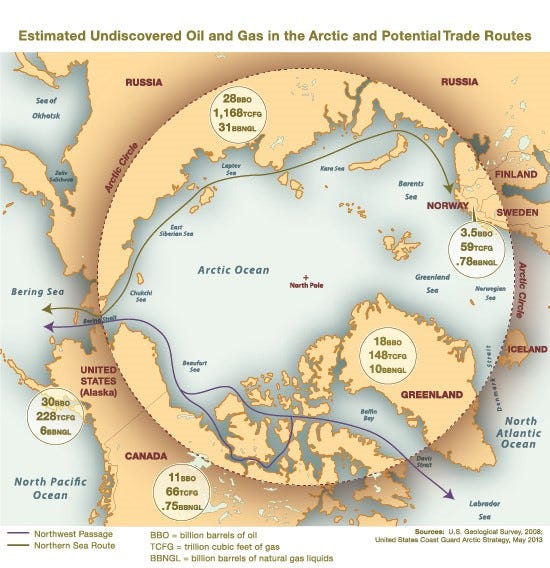

This is also true in the imminent tussle – primarily between the US and Russia – over artic drilling, where who owns the resources as well as the shipping lanes is not well-defined.

Part 3: The fossil fuel industry

In this piece, I have tried to separate oil as a product from both the countries involved in its lifecycle as well as the companies that do so. Particularly when it comes to the fossil fuel companies, this distinction becomes harder because our collective access to oil is through these companies alone, but I urge you to view them as part of a particular system that is distinct from the product – meaning that our use of oil could have been, and maybe still can be, different and less destructive.

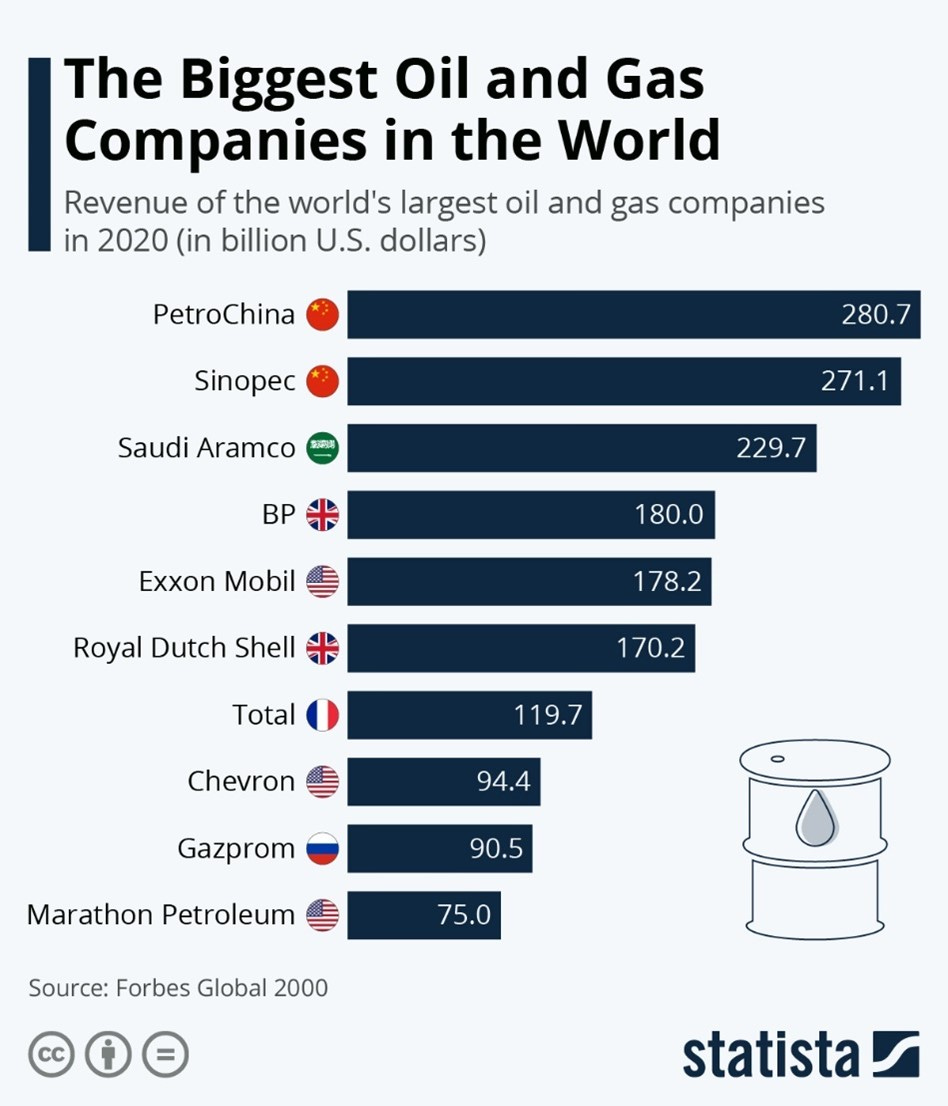

The oil & gas industry is dominated by a handful of national oil companies, followed by the 6 supermajors (privately owned multi-nationals: Shell, Exxon, BP, Chevron, TotalEnergies, and ConocoPhillips). You might be surprised to learn that PetroChina and Sinopec are larger in terms of revenue than even Saudi Aramco – just goes to show how dominant China is even in the O&G value chain. Remember, China doesn’t produce crude oil, so these revenues are earned through refineries.

The private companies in particular have been in the news a lot recently because of accusations related to “crisis profiteering” – that these companies used the supply shocks from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Covid-19 related supply chain issues to engage in price gouging, fueling the cost-of-living crisis. Regardless of how you view that, the fact is that the supermajors earned $200B+ profit just in 2022 – an industry record.

Saudi Aramco just announced $161B of profits for 2022, the largest for any oil & gas company in history.

[The grey line represents the combined profits for the 6 supermajors]

While some have deemed this unethical and asked for a windfall tax, especially given the global inflationary context, others have defended this by saying that these companies deserve this big win because oil prices had been low for over a decade prior to this recent episode.

However, let’s be clear that it is not like these major companies were struggling to make money before. They have been making billions of dollars of quarterly profits for two decades, engaging in M&A activity, and expanding their market power.

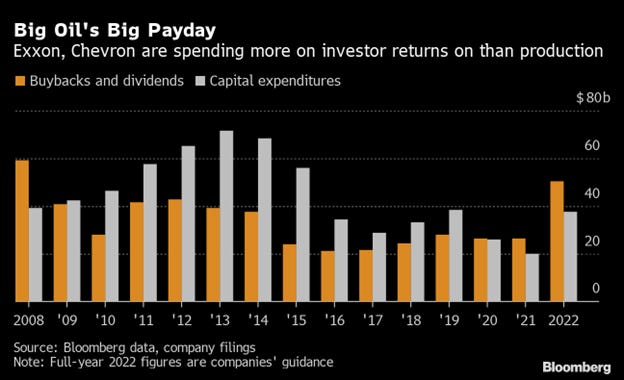

Despite this recent cash influx, these companies are not looking to substantively invest in renewable energy investments, or even new fossil fuel projects to improve efficiency, environmental standards, etc. Instead, these profits are leading to a surge in buybacks and dividends, a trend that has been in place over the past decade.

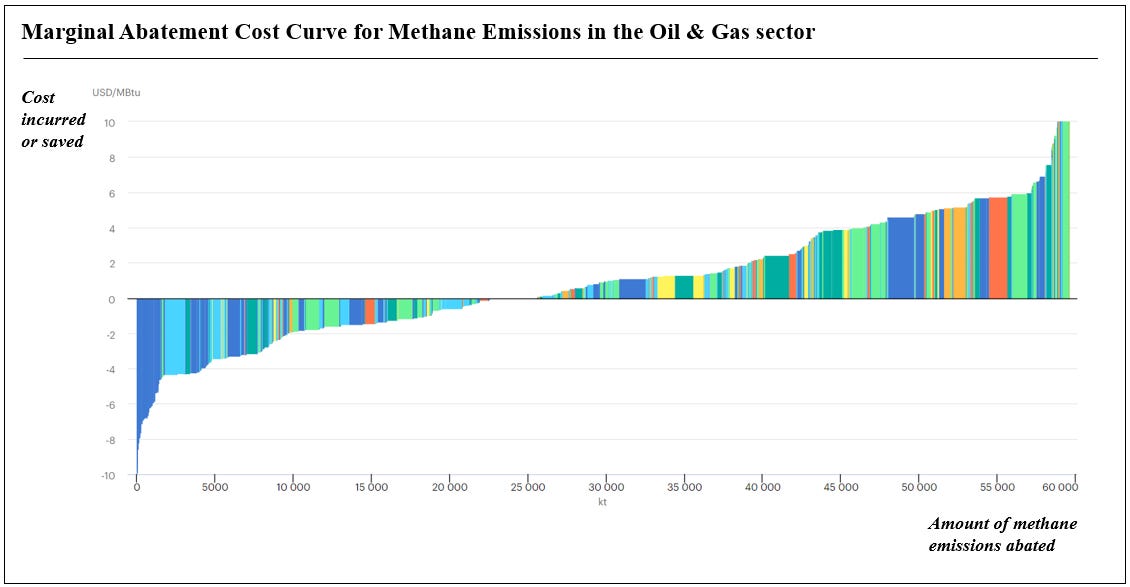

On the other end is the fact that many emissions abating activities from the oil & gas sector — in the example below its methane emissions — are not just well-documented but also cost negative, meaning that enabling those measures would both abate emissions and reduce costs! And yet the industry is not embarking on these measures, let alone investing money in making the more expensive one’s feasible.

Another common complaint of the sector is that decarbonization efforts are being subsidized and hence have an unfair advantage. But let’s look at the facts. Subsidies to the fossil fuel sector are astonishingly high — and increasing.

According to a report by the IMF, the fossil fuel industry received $5.9 trillion (yes, with a T) of subsidies globally in 2020 – the number was higher in 2019 and expected to increase past 2022. Of this, the petroleum sector received 28% of implicit and 46% of implicit subsidies. The implicit subsidies totaled $5.5T out of the total $5.9T by the way.

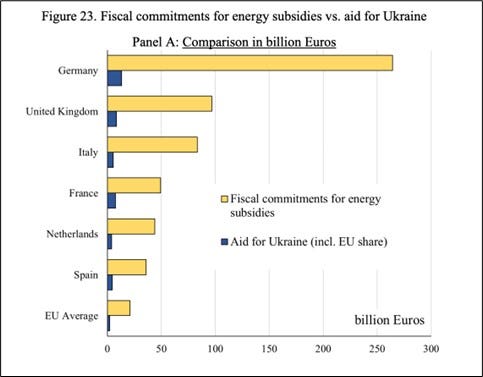

Here’s another interesting way to look at subsidies. Western governments have doled out subsidies to consumers to protect them from higher energy prices. All that cash has essentially funneled back to O&G companies because consumer demand remained relatively stable while prices were significantly higher.

With all this free money, it would be hard not to be profitable. So much for the victimization narrative from the industry!

Threats to decarbonization

In previous pieces, I have explained how decarbonization only occurs if the absolute amount of fossil fuels goes down, not the % of our energy mix. Achieving that requires a lot more than what we have conjured up thus far, despite a roaring decade for renewables.

The last point I want to explain here is how the state of the O&G sector threatens decarbonization. Here are 3 key points to think about:

Fossil fuel subsidies are 20x compared to renewable energy subsidies (source: IRENA)

Big financial institutions are still heavily funding fossil fuels. Remember, banks create money through lending – that is what drives investment.

O&G is more profitable. We hear a lot about how renewables are cheaper and hence economic logic necessitates their prioritization. However, under capitalism profit drives decision-making. There are claims that because of higher market concentration and ability to exert market power, among other things, is possible with fossil fuels compared to renewables, the latter is less attractive.

Important to realize that prior shifts in energy sources, for example from coal to oil in the early 1900s, were not driven by cost necessarily but by profit margins and ability to exert control over workers (coal is labor intensive and labor strikes against horrible working conditions were increasing).

The winds of change around decarbonizing are also shifting. Over the past few years, both the O&G companies and the large banks jumped on the “green” bandwagon and announced net-zero plans. It has taken 1-2 disruptive years to wash away that veneer as these companies have reneged on their commitments.

🚨 Blackstone, Blackrock, KKR, Carlyle Group are among the investment banks and PE firms that have recently expressed concern about ESG restrictions hindering their returns and fundraising.

🚨 Shell, Exxon, and BP have reduced their previous climate commitments, either by reducing their emissions reductions targets or reducing funding. Their renewable energy investments are already abysmal.

🚨 Biden’s administration, while being lauded for passing the largest “climate investment bill”, has approved O&G drilling permits at a faster rate than Trump (source). He also might be approving a massive, $8B drilling project in Alaska. So much for a climate-friendly president.

Given the current structural setup, it makes sense. This is a sector with growing demand, with potential demand tailwinds (reindustrialization, onshoring, and war require more fossil fuel consumption) as well as positive price shocks (geopolitical risks, supply chain disruptions, etc.) at a time when capital investments have been very low, meaning that new supply will be constrained.

[No, I am not defending this. My point is that this is a structural problem that cannot be fixed through pushing “climate commitments” or other such tactics while the current system remains in place.]

Why this matters

Energy is the driving force of life and civilization. We need energy that is cheap, accessible, and energy efficient (meaning small amounts of energy are required to used that energy. The visual below shows how over the past century, we have had a declining energy return-on-investment (EROI) — more energy needs to be reinvested into accessing future energy sources. As this aggravates, due to decreasing energy quality, geopolitical fracturing, economic crises, etc., strains on energy will exacerbate.

Oil is the energy source at the heart of it. We cannot reduce our dependence on it in a minimally disruptive way without fully understanding the role it plays. I would argue that this is why, despite almost three decades of climate conferences and commitments, fossil fuel consumption, carbon emissions, and ecological damage is continuing its uptrend.

Also, if our decarbonization and energy self-sufficiency narratives are based on shaky grounds and techno-utopian hopes, the likelihood of failure and whiplash will be severely damaging.

The last point, and perhaps the most salient, is that the Global South is still severely energy poor. Whether it is in terms of food, infrastructure, electricity, or other material consumption, improving social well-being will be energy intensive. And since, as Vaclav Smil stated, the core of all these elements is fossil fuel dependent, there is going to a demand surge.

The reactionary movement to decarbonization (like Alex Epstein, Konstantin Kisin, and others) use this as a reason to protect the fossil fuel industry and undermine decarbonization efforts. This, in my opinion, is simply farcical because:

Somehow when it comes to fossil fuels, poor people matter but when it comes to dismantling systems of exploitation this doesn’t come up.

This a “more growth” fallacy — if decades of growth and fossil fuel consumption hasn’t sustainably achieved global wellbeing, then more of it won’t do it either.

Rich countries and people substantially overconsume. There is nothing stopping us from redirecting the oil they overconsume towards the developmental needs of the Global South

Oil, and fossil fuels in general, disproportionately harm the Global South and vulnerable communities. See this example of an Ecuadorian community that has been poisoned for decades by Chevron’s grotesque, and conscious, malpractice.

We can, and should, separate the product from the system. Just because we need oil doesn’t mean we need in the current unequal, unjust, and exploitative system where a handful of companies rake in profits and have incentives that are at odds with humanity’s future. Remember, scientists from these fossil fuel companies knew about climate damage as far back as the 1970s but were suppressed and these companies have for decades funded misinformation campaigns and political corruption.

To conclude, it is undoubtable that oil is an inextricable part of our life. We need to better understand and acknowledge that to build better alternatives. In the meantime, there is nothing stopping us from have a more just, equitable, and healthy system that uses as a vital resource achieving global wellbeing.

Resources

Vaclav Smil - Oil (book)

The Great Simplification - The Devil is in the Diesel (podcast)

The History Channel - How We Use Oil Everyday (documentary)

Such a clear and comprehensive explainer. I would recommend this book too as a resource: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Oil-Power-War-Dark-History/dp/1603587438