#4: Money, myths, and debt

Understanding money is critical to the global system but the mainstream narrative gets it wrong.

[Author’s note: As a recap, my goal with this newsletter is to build out a map of the global system, starting with explaining the most important nodes from a high-level (first energy, now money) and gradually delving deeper into the specifics.

This piece is slightly longer that I would’ve liked but money is just too important a topic to not warrant some extra explanations. The problem with this topic is also that we all have a lot of preconceived notions, so getting away from those can be hard. I have a bunch of resources at the end to support the cause!

I hope this effort helps and as always, please share/subscribe/provide feedback!]

2022 was the year of energy. Will 2023 be the year of finance?

Headlines about an impending sovereign debt crisis, government bankruptcy, financial bankruptcies, etc. have been around for many years. Recently there was a headline that seemed to warn about a massive financial crisis brewing: $80 trillion of global debt was “hidden”, as reported by the Bank of International Settlement. I don’t need to elaborate on how big that number is of course.

Money is one of those things that we think about on a daily basis and yet rarely do we get into asking what money actually is. Econ 101 tells us that money is a medium of exchange, store of value, etc. – but those are features, not a definition. For example, is something a medium of exchange because it is money or vice versa?

[Econ 101 uses circular definitions a lot – that’s for another time]

So in this piece, we are going to explore what money actually is, where it comes from, how it gets created, etc.

To make it more readable, I will be breaking this into two parts:

Part 1: Conceptual understanding of money, how money gets selected, etc.

Part 2: Specific application to today’s world, national debt, banking, etc.

The 5 questions I answer in this piece are:

How money fits into the big picture?

What is money?

How is money created?

How is money chosen?

What form does money take?

Note: True to the principles of this newsletter, this isn’t a political or ideological piece. This is simply a factual explanation of how money works.

This part is going to be more conceptual so as to build a logical framework around money while in the second part I will be covering specific contemporary examples and implications.

How money fits in the big picture

First, I want to illustrate why this is a critical topic and where it fits in the larger model of the polycrisis. Earlier I mentioned the debt crisis but there are a host of other concepts within our global system that depend on money (some of which I mentioned in newsletter #1):

🎯 Global trade: Energy, food, medicines, computers, etc. – essentially every aspect of our life depends on trade, and trade depends on money. This is inextrciably tied to debt crises (e.g. Sri Lanka in 2022)

🎯 Social development: Supporting the population through economic crises, for example Covid-19, or generally supporting healthcare, education, etc. Remember the infamous Obama quote during the 2008 financial crisis which limited his expansion of social services: “we're [the US] just taking out a credit card from the Bank of China”.

🎯 Future investments: Investing in renewable energy, developing/upgrading infrastructure, building affordable housing, etc.

The bottom line is that a lot of policymaking and politics revolves around the question of “can we afford it”, and yet there is very little effort to understand what affordability means.

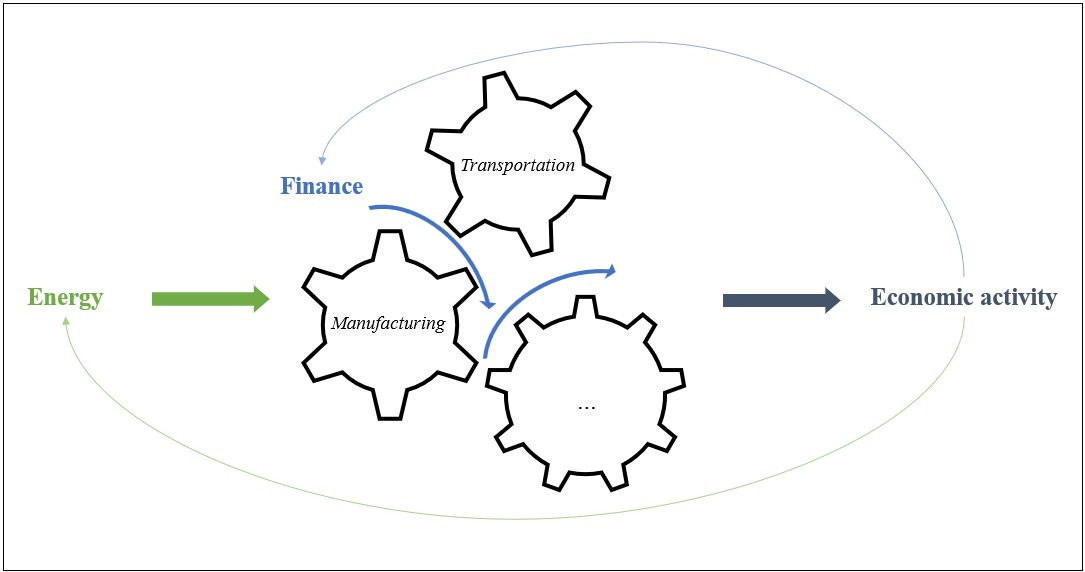

In newsletter #2, I explained the importance of energy as the thing that underpins the whole system – quite literally. Money is at the same level of importance. It is at the center of the global order, giving structure to the regime, connecting nodes of the network, removing frictions, and opening up new frontiers.

An analogy that might be useful is that if the global system is a machine, then energy is the force driving the cogs and money is the grease allowing the cogs to work together. These two concepts together are the core of the system.

I will note that the important difference between the two concepts is their nature: energy is a physical reality, bounded by natural laws; money is a socially constructed, abstract concept – its shape and limitations are bounded by our creativity and sociopolitical setup, not natural laws.

Since this is a complex topic with many facets, I intend to follow this up with a series of newsletters that cover the US$ as a reserve currency, the Eurodollar system, Global South debt, etc.

[P.S. If you want a long, detailed read on money, its history, inflation, and Bitcoin, I wrote a 3-part essay over the summer. Here, here, here]

A parable to get things going

Imagine a tourist comes to a small, rural town and stays at the local inn. They are required to pay 100 diamonds (that’s what the town uses as money) as a damage deposit. The next day, the inn owner realizes that the tourist has hastily left town, leaving behind the 100 diamonds. Given that it is unlikely the tourist will venture back, the owner is delighted at this turn of events: a 100 diamond bonus! The inn owner heads to the local baker and pays off his debt with this extra money; the baker then goes off and pays off her debt with the local mechanic; the mechanic then pays off his debt with the botanist; and the botanist then pays off her debt at the local inn. So the 100 diamonds have come full circle and 4 people in town are now free of debt!

This isn’t the happy ending though. The next week, the same tourist comes back to pick up some luggage that had been left behind. The inn owner, now feeling bad for still having the deposit and liberated from paying off his debt to the baker, decides to remind the tourist of the 100 diamonds and hand them back. The tourist nonchalantly accepts them and remarks “oh these were just glass anyways,” before crushing them under his feet.

[Source: Somewhere online]

What is money?

[Let’s try to start with a clean slate and forget what econ 101 has taught us about money – I will come back to that at the end]

The primary use of money is that it a claim on resources.

That should be a fairly uncontroversial statement. We acquire money through various means primarily to buy goods & services. We save and invest money so we can buy more stuff in the future. Money in and off itself has no other value.

[For the sake of intellectual honesty, I want to point out that Marx’s analysis of money rightly identifies the social power of money on its own – the value that just comes with being rich – but for this explanation I will leave that out]

Now that we know what the use of money is, the question is where does it come from?

Money is an IOU – “I owe you”.

An IOU is a contract or note that acknowledges that one party owes another party something. When person A issues an IOU and hands it to person B, the former is acknowledging their indebtedness to the latter. For Person B, the IOU is a future claim on resources (whatever the two parties agreed upon). That contract or claim is money.

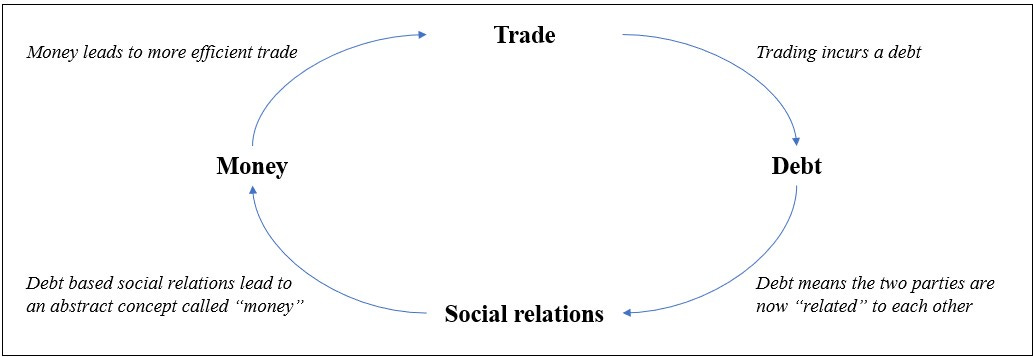

Therefore, money = debt.

As you multiply these bilateral transactions across a community, you can see how they cancel out. On average, most people owe another person something and are also owed something from other people. The key thing here of course is what exactly do these people owe each other? If everyone owes a different good or service (sheep vs wheat vs a day’s labor) it would be very hard to equate, and hence cancel out, debts, making the whole thing inefficient. That’s where this abstract notion of money comes in. An arbitrary unit of account that can price all goods and services into the same unit.

[This may seem obvious and standard thus far but continuing this money = debt concept leads to major implications away from the mainstream narrative.]

Let’s assume that unit of account is something called the “dollar”. If everyone in the community recognizes the dollar as money, suddenly it makes things a lot easier from a trade and commerce perspective. This is the point about money being grease that allows cogs to work together: individuals, firms, governments, etc. don’t have to waste time equating how many sheep would be equal to 10 logs of trees or whatever.

Another way of putting it is that since society is basically a collection of people doing stuff (someone cooks, someone builds, someone teaches), our social relations depend on being able to trade these goods and services.

Money is, therefore, a representation of our social relations because it is what our trade is denominated in, and trade connects people with each other.

So to recap, money is debt (if there was no debt there would be no money) and a representation of social relations.

The reason this is important is that getting the story right about “where money comes from” is critical to understanding everything else. Mainstream economics does not think about money in terms of debt or social relations!

How is money created?

Another way to think about the aforementioned concept is simple accounting and balance sheets. Accounting isn’t the most thrilling subject , but we just need to work with the most basic principle: every asset needs to have a matching liability.

Someone’s asset must be, by design, someone else’s liability.

Expressed in this way, it is quite easy to understand money.

Let’s run an example, with a step-by-step breakdown:

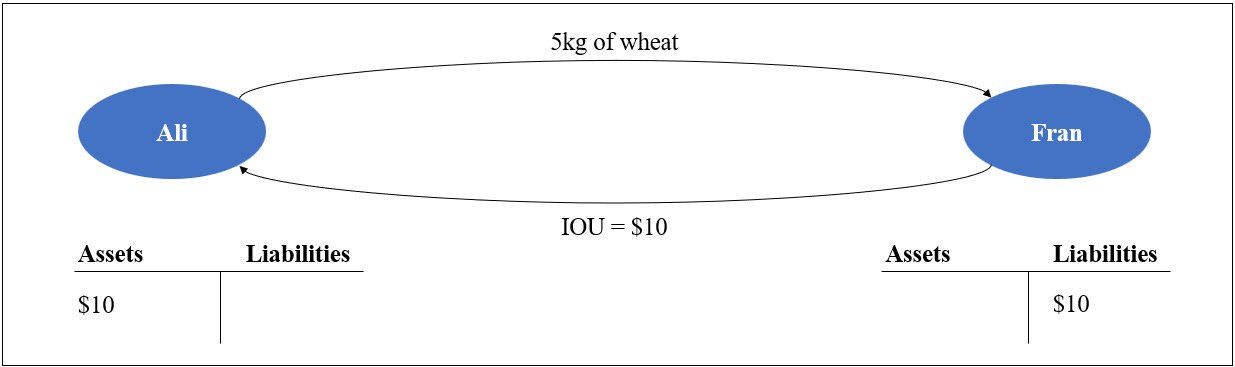

☛ Ali gives Fran 5kg of wheat

☛ Fran now owes Ali 5kg worth of wheat – for this, she hands back an IOU to Ali. Fran’s liabilities have gone up by 5kg of wheat

☛ Ali receives this IOU and now has an asset worth 5kg of wheat

Now, let’s assume their community also uses the dollar and so wheat can be priced in that. All you have to do is replace the 5kg of wheat on the IOU with the dollar amount – everything else is exactly the same.

And thus, in one fell swoop, money is created by the necessary act of the issuer going into debt and the receiver gaining an asset. This is called double-entry bookkeeping and has been around for thousands of years.

Now Ali can take Fran’s IOU and use it to buy milk from Sam, and so on. Just to complete the circle, assume that in the future Sam buys oranges from Fran and offers her the IOU as payment. Fran’s debt is now cancelled – shes owns her own IOU.

Therefore, paying back debt in and off itself destroys the money that was initially created.

This was of course a highly simplified example where we assumed that there was a common unit of account, that the IOU issued by Fran had any worth to Ali and Sam, and that there was a market that set the price of each good denominated in the common unit of account. Let’s explore the first two assumptions next.

Note here that money is not like energy, such that there isn’t a fixed amount that circulates the economy and “money printing” is not some external intervention. Money is constantly being created and destroyed in economic transactions (admittedly, this is still abstract-ish but part 2 should fix that!). But recognizing this fact about money, as I said above, critical!

How is money chosen? The role of authority

“Everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted” – Hyman Minsky

In the story above I just assumed that everyone in society decide on a common unit of account. This, of course, is fanciful thinking because nothing ever gets chosen so easily.

[Btw, this is what mainstream economics assumes. Economics just assumes that barter - which never existed also - suddenly gave way to a common unit of account]

Let’s continue with the story. Since money is debt, then basically every time I am indebted to someone, I am creating my own money, and every time you are indebted to someone, you create your own money. Whose debt should become the socially accepted form of money?

The answer to this question is a hotly contested point (to which I gave my own thoughts in the essay series mentioned in the intro) but for now, a middle-ground answer would be that an entity that has sufficient social power ends up issuing the form of money that becomes the local currency. Today we have a system where each sovereign nation (excluding places such as the EU or the African bloc still kept on the CFA Franc) issues its own currency. Hence, the national government is that entity. There have been periods in the past where currencies were more “competitive” such that various financial institutions would issue their own currency and so you could have multiple currencies in the same economy.

The point is that money is only useful if everyone will use it, and everyone will only use it if they think everyone else will use it and that there will be some laws against counterfeit, theft, etc. So it makes sense that an authority with sufficient power selects what becomes money and then governs its use – when the power of that entity dies, the money goes with it. This also fits nicely with the social relations point since power also mediates social relations.

An easy way to think about it is that almost all governments levy some form of tax on their population. Let’s use Pakistan as an example. The country was founded in 1947 and had to develop its own monetary system. Did the people get together to decide the currency? Of course not. And where did the currency physically come from?

The government issued paper currency for usage and gave that currency (the rupee) legal tender status. That meant that all legal dues (fines, taxes, etc.) could only be settled in that government issued currency. For people to not break the law (i.e. pay their taxes and fines) they had to have access to that currency, and since the only way to do that apart from a government salary is commerce, the rupee became the local currency for the market.

So to bring it all together, the rupee is issued by the Pakistani government via the same debt process described above – it goes into debt when money is created while the receiver, say a private sector entity (firm or individual), sees an increase in its assets by the same amount.

The sovereign authority is what makes the government’s debt (money) the local currency, which is why all market participants are not hesitant in using it for business activity.

This is true for every other currency-issuing government as well.

Can anyone else issue a currency? Yes, anyone can issue a currency (i.e. their debt). But why would people use it?

Can anyone else issue the national currency? Yes, only if they are state sanctioned to do so (i.e. banks). Banks are special private entities that receive a charter allowing them to create the local currency. The state then regulates the use of this privilege. If anyone else attempts to issue the currency, that is counterfeit and illegal.

[More on banks and the myths around them in Part 2]

Whether a government is always needed for a local currency is a subject of intense debate. I am not going to get into that – what matters is that some authority is needed to give money its status, and that one of the more obvious sources of that, including in the current system, is the sovereign.

I hope that by this point you are beginning to see why the mainstream understanding of national debt and the urge to run government supluses is misplaced and is based on a flawed conception of money.

What form does money take? The hierarchy of money

While I have explained conceptually what money is, its manifestation in the real world varies across time and space. For example, today we have paper money, we have digital money (money held in banks), etc. The historical example that everyone knows off is gold/silver coins as money. But there have been many others forms of money across various contexts: tally sticks, seashells, rai stones, local bank notes, etc.

“Money has no essence. It's not "really" anything; therefore, its nature has always been and presumably always will be a matter of political contention.” – David Graeber

The short answer to this is that, since money is about social relations, the setup of the monetary system is a sociopolitical outcome. Any object can take the form of money if it achieves the goals mentioned above. Admittedly, each form has its own value proposition: metallic coins are most durable, digital money has more efficiency, paper money has privacy, etc.

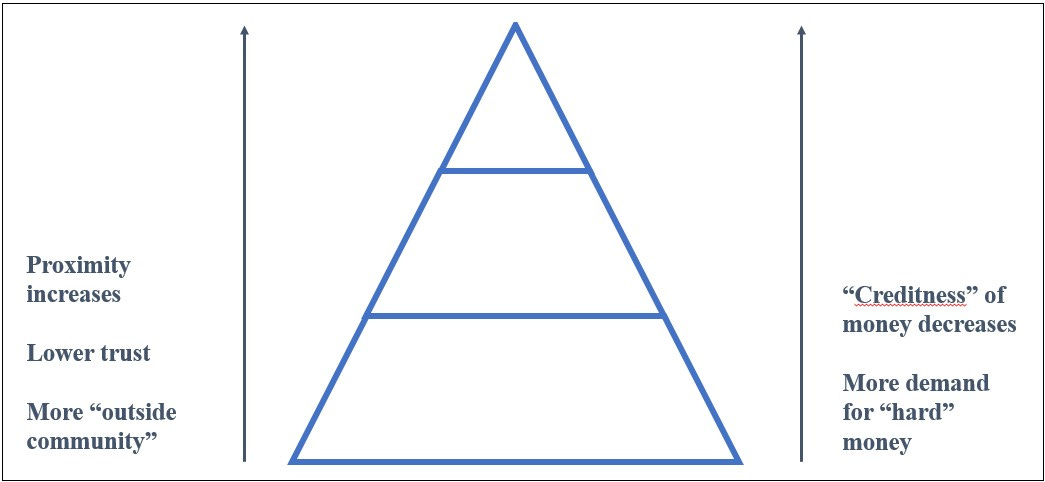

The concept to think of here is that there is never really one form of money operating in a system. There is, instead, always a hierarchy of money. This is simply an extension of the concepts I explained above. Here’s how:

Let’s say you are engaging in trade within your community. This means that there’s likely a communal connection between you and the counterparty, as well as a high likelihood of repeat transactions. Hence, maintaining a cruder form of debt – i.e. having a tab on both sides that just cancels out, or something like Splitwise today – is sufficient. So at that base level, the “debtness” of money can be high.

Alternatively, if you engage in trade with a “foreign” counterparty, either someone outside the community/tribe in older times or outside your country today, trust is likely to be lesser due to lower proximity. In this situation, both parties want a form of money that has some stature outside of their bilateral relation.

Hence, “higher” forms of money become more relevant: gold/silver coins, US$, etc; stuff that is more globally recognized. This of course still has a certain level of trust, since both parties need to value it, but you’re at least not accepting the debt of your counterparty.

In Part 2 I will explain how the hierarchy of money looks like today.

Conclusion

[If you remain unconvinced thus far, in Part 2 of this piece I will be using real world examples for today as well as providing a lot of external resources that do a wonderful job of explaining.

This is also just a very preliminary introduction - this topic has been discussed, analyzed, and fought over for eons so there is a lot to unpack and build going forward]

None of this is a new concept. In fact, some of the earliest forms of writing in human civilization are said to be a form of record-keeping about debt. Econ 101 talks about how first barter existed and then at some point people realized that money would be more efficient – that is a myth. People have been using debt to engage in commerce for thousands of years.

Econ 101 also perpetuates this concept of money being some thing that just exists, and that all participants (firms, governments, people) are fighting to get access to it. It is built around the image of gold in a mine that everyone is racing to mine and control (or gold in a vault). This is the concept of money as exogenous – i.e. it is something exists outside the system. If the government uses too much of it, the private sector won’t have enough, and so on (what is called “crowding out”).

As I hope you see by now, this is a complete myth. Money is, and has always been, endogenous – i.e. it is created within the system when relevant participants interact. It is relational – i.e. it links creditors and debtors. It is not a pot of gold waiting to be found, it is merely a system of accounting to record the credits and debits (or assets and liabilities) of all economic agents.

This is why it should be evident at this point that comparing governments (money issuing agents) to firms or households (money using agents) is grossly incorrect.

The concept of tightening belts and using the analogy of cash-strapped households to scold governments is just political point-scoring, it has nothing to do with the real world.

Again, this is not political. This is not what money should be, this is what money is. This is a fact.

The role of government is also a documented fact. Not too long ago, when French colonialists went to some African societies, they wanted to get the local population to build infrastructure for them. Rather than constantly using force, which they did of course, they issued a tax on the local people payable only in the French currency. Pay taxes or we burn your house down was the message. The only way for the local population to access French currency was to work for the colonialists – hence, suddenly they had a population “willing” to work for them (source).

Extrapolate that to today where the US$ is the world’s reserve currency (reflecting the superpower status of the US). Since the US$ is needed to engage in global trade, countries essentially have to figure out what they can offer (cheap labor & raw materials usually, or geopolitical access in Pakistan’s case) in order to access US$.

The implications of this are not just geopolitical – everything is about money and what we can afford. Without money, you can’t access real resources (energy, food, medicines, etc.)

Scams work in this way too. FTX’s implosion is basically about a company issuing its debt as money (FTT crypto-tokens). When trust in FTX went away, the currency (FTT) went to 0. Perfect illustration of Minsky’s quote!

In part 2 of this (which will come out soon), I will explain in more detailed how money in today’s world works, focusing particularly on the hierarchy of money, the global banking system, national debt, the Global South debt trap, and what avenues of analysis this opens up.

Resources

Books:

Debt: The First 5000 Years - David Graeber

The Currency of Politics - Stefan Eich

The Deficit Myth - Stephanie Kelton

Why Minsky Matters - Randy Wray

The New Economics - Steve Keen

Videos: