#3: Stocks don’t always go up

How risk & uncertainty might impact the buy-the-dip market we’ve become used to.

[Author’s note: This was a fun piece because it makes what I have been writing about actionable and relevant for people’s daily lives. Although the markets I focus on are US-based, I think the general themes are broadly applicable.

If, like me, you enjoy looking at price charts, then this might be quite fun for you!

Disclaimer: In no way is this meant to serve as investment advice; the purpose is just to expand the range of possibilites in our imagination and prepare accordingly.

Also, I made the body of this piece shorter than previous newsletters and put a bunch of stuff in the appendix for extra reading. Hopefully this makes it more readable. On that, would appreciate feedback for further pieces:

Please subscribe + share + provide feedback; eager to find ways to improve and make it more worthwhile for readers!

Follow me on Twitter!]

Source: The Denver Post

Introduction

Many people engage with the stock market as casual observers witnessing a distant, but at times enteraining, game. And yet, for better or for worse, the stock market is an essential cog in our lives, operating at multiple levels across the system. Here are some ways that it probably impacts you:

🎯Wealth creation / early retirement: They say you can’t save your way to retirement, you can only invest your way there. Investing in equities is perhaps the most mainstream way to build wealth faster than expected. How many people do you know who made life changing money by investing early in Tesla or Apple or Amazon?

🎯Wealth preservation: Whether in their retirement account, pension fund or kid’s college fund, everybody feels the need to protect their wealth against inflation (and maybe have a small but steady growth rate). The stock market is an essential tool to achieve that.

🎯Real economy: The stock market drives the economy and vice versa. Whether through stock based compensation in companies or getting hired by firms able to consistently improve their valuation, employment and compensation are relatively closed tied to what happens to stocks.

Therefore, it is imperative to understand where we are in that story and what could happen. There are multiple ways to do this but in this piece specifically, I am primarily going to be relying on historical analogs to expand the range of possibilites in our imagination as opposed to providing a conceptual explanation of how the stock market works.

It’s simply not enough — maybe — to have our understanding of stocks be reduced to “average annual return of ~10%”. Hopefully with a little bit of effort, a more effective understanding can help prepare us for what might come.

Summary

The implosion of the FTX fraud serves as the perfect backdrop to this (from a valuation of $40B to bankruptcy within days). You might say that cryptocurrency is a scam and hence this was bound to happen. But think about this: FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried (the founder/CEO) were cajoled by some of the biggest VCs and investors in Silicon Valley, the people who are supposed to be allocating capital efficiently.

Dissecting what went wrong isn’t the point of this; the biggest learning here is that maybe there is a lot of fictitious capital out there and stamps of approval by professionals isn’t proof otherwise. If FTX, this incredibly public-facing and well-known company, and its wealth could just evaporate (including that of the employees and customers), what does that say about the overall health of financial markets?

The common wisdom related to the stock market is typically:

Stocks always go up (in the long run) so buy the dip!

Just buy and hold index funds and big companies

Compound interest FTW!

[If something is common wisdom, it’s worth double checking its veracity anyways]

In this piece, I present a potential alternative hypothesis. My primary argument for being skeptical is that this suffers from recency bias and acts as a self-reinforcing cycle – until it doesn’t. If you are following the theme of this newsletter, then you might be getting convinced that the global regime is fundamentally changing. Why then should we assume that financial markets, which are inherently avenues for risk-taking, won't also be seriously affected?

In summary, my hypothesis is simple: the base layer that underpinned this recent period of high returns is changing, and any volatility & uncertainty at that foundational level will reverberate across the system.

The question to ask yourself is what happens to risk-taking in a world with increasing geopolitical + supply chain + financial liquidity + energy + inflation/recession risk?

[Newsletters #1 and #2 layout the frameworkfor this]

“Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.” - Warren Buffet

Market overview

Let’s start by looking at where the market is right now. Since the conventional wisdom has been to have a 60:40 portfolio (60% stocks and 40% bonds), I am going to start with those two asset classes.

[If you want to see some wild stock charts btw, check out the appendix]

Figure 1: Global and US stock indices

(Global stocks: -28%; US stocks: -22% — numbers change on a daily basis)

Both US and global stocks are down considerably, although given the context of the surge higher since March 2020, stocks are basically back roughly to where they were at the start of 2021.

Figure 2: Global and US government bonds

(Global sovereign bonds: -35%; US govt bonds: -35% — numbers change on a daily basis)

Governemnt bonds are typically considered to be safe assets with low volatility and with a negative correlation to stocks (i.e. they either go up or at least retain their value when stocks go down). This year, however, we have not just seen bond prices go lower along with stocks, but bonds have performed worse than stocks. Very few people were expecting that. In fact, bonds have had their worst year in over a century. Talk about things fundamentally changing this year.

Figure 3: 60% stocks & 40% bonds portfolio performance

Hence, it comes as no surprise that the 60:40 portfolio, which is a relatively safe portfolio designed to grow wealth over time and isn’t some go big or go home play, is having its worst year on record. There is some serious wealth destruction that has occurred this year, and I am not even talking about the people who lost money speculating on Gamestop and crypto. Just this chart alone should be screaming that the current situation isn’t normal by any means.

The last time something like this occurred was during the Great Depression!

So the logical question here, especially given of common wisdom I started with, is that is this a good time to buy stocks? There are two ways I am going to evaluate this claim: price & time.

Catching a falling knife

By historical standards, the current bear market has been relatively shallow (-22%), especially if you consider the most recent examples of the 2008 Financial Crisis and the 2000 Dotcom bubble (-52% & -46% respectively) — using the S&P 500 index as the measure. Also, interesting to note is the length of the current downturn as compared to previous ones – bear markets tend to last for over a year, sometimes multiple years. The current one started in Jan 2022 and hasn’t even reached its 1-year mark.

Figure 4: US stocks bear markets — S&P 500 index

(log chart)

It’s also informative to look at the market leading stocks across various stock market crashes to see how we compare. You can see how during the 2008 Financial Crisis the big tech stocks were down ~50% from their highs, while the equivalent companies during the 2000 dotcom bubble fell ~80% during that crash (the big ones during the late 1990s were part of the PC/Internet revoltion: Cisco, Microsoft, Intel, etc.)

Figure 5: Market leading stocks across 2022, 2008 and 2000

(Orange line shows the trajectory of the big tech companies in 2008 while the yellow line shows the trajectory of the previous generation of big tech companies in 2000; in 2022, big tech -- Apple + Google + Microsoft — are down ~25%)

Looking at the more speculative end of the market is more fun though. The dotcom bubble is famous for having new, world-changing technologies soar in stock price, buoyed by investor frenzy and a “can-do-no-wrong” attitude. Sound familiar?

You don’t even have to look at individual stocks (such as the infamous Pets.com) to see the carnage: the Nasdaq 100 — the US tech stocks index — lost 83% of its value from 2000 to 2002.

A similar event has already played out this year in the now infamous ARK Invest fund. This hedge fund put together ETFs that bought only high-growth, disruptive technology companies (e.g. Tesla, Zoom, biotech companies etc.) and soared 316% from March 2020 to the peak in 2021. However, in an eerily similar trajectory to the dotcom bubble, it has crashed 75% in price since then.

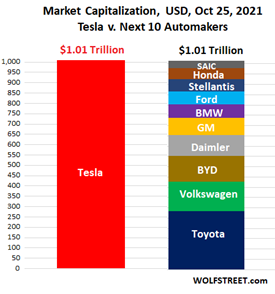

Sidenote: The market favorite of this generation has been Tesla, complete with its massive fanbase, star CEO, and disruptive technology vibes. I leave the chart below without further comments.

Figure 6: Tesla compared with ARK Invest (2022) and the NASDAQ 100 (2000)

(Log chart)

[Note: I admit this is a spurious correlation and not meant to be scientific in any way. But that’s also kind of the point. This time could be different, or it couldn’t be. It’s good to just consider the possibilities.]

I won’t belabor this point further and will leave you with three quick tidbits.

In 2021, Tesla was worth more than the top 10 car manufacturers combined while having only 1.2% of the market share.

In 2020, Apple was worth more than the entire US energy sector (hopefully newsletter #2 was enough to put energy on a high enough pedestal to know how absurd this was).

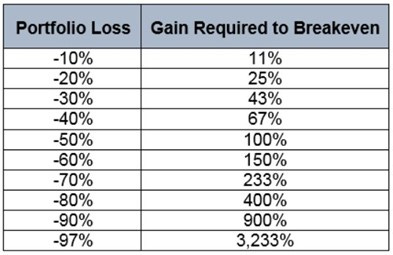

Percentages are a funny and deceptive concept. They make us believe that the magnitude of the impact is the same regardless of direction, but that’s not the case. You need exponentially larger moves on the upside to make up for moves to the downside. Big difference between being down 40% or 50%!

Source: Twitter (@KoosKanmar)

Therefore, price falling sharply could be a great buying opportunity or you could be catching a falling knife – if it keeps falling, it could leave quite a mark.

[If you want to delve deeper into the price angle, I have a section in the appendix on company valuations – using price to earnings ratios – and what they tell us about whether stocks are cheap]

The lost decade: death by a thousand cuts

It’s one thing to lose money when price falls, it’s another to have price be stagnant for long periods of time and lose value to inflation. Our recency bias has made us so used to sharp market rebounds that relatively few people are mentally prepared for the possibility of the market just being flat for maybe a decade.

Legendary investor Stanley Druckenmiller has been warning about this recently.

Figure 7: US stock market long-term chart — S&P 500 Index

(log chart)

This chart goes back all the way to the late 1800s! The important thing to note is not the price declines but the length of time that prices stay roughly flat or stuck oscillating between a horizontal range. For example, in the early 2000s, the stock market went sideways for almost a decade; in the 1970s, it went sideways for over a decade.

Nominal returns are only part of the story, however, so let’s make it more realistic by looking at inflation adjusted returns for the same index.

Figure 8: US stock market index inflation-adjusted returns

(log chart)

When adjusted for inflation, stocks can remain flat for a very long period of time (ranging from 1-3 decades).

That means that, depending on when you bought, there’s a high probability that in inflation-adjusted terms your stock portfolio could be stagnant over decades.

The same way I showed in the tidbits above that price declines can compound against you (need exponentially higher positive returns to make up for bigger price declines), similarly price staying flat for extended periods can “compound” against you as well as you bleed money year-on-year to inflation.

Could you sit patiently if your investments were returning nothing for a decade? Should you?

There’s always a bull market somewhere

It’s not all doom and gloom though. Investors always find places to park their money and make returns. One of the possibilities that fits the theme I have been talking about in previous newsletters is commodities (energy, metals, etc.)

Let’s use the same framework: there is a fundamental shift in the world we have become used to in the past few decades. This means that what has been hot (technology & related themes) may be on its way out — relatively speaking of course, we are not going back to an analog society — and what has been ignored (commodities & energy) could be making a comeback.

Luckily enough, the financial evidence tells a similar story. Relative to the stock market in general (which is dominated by tech giants remember), commodities & energy are historically cheap. Not only that, but commodities also tend to perform much better than the general stock market in recessionary and inflationary periods. It makes intuitive sense as well: when times are tough, people are less likely to be thinking about buying new gaming consoles and iPhones than about food, energy, basic materials, etc.

Our current situation is also unique because we are facing a concurrent demand surge (especially if we are serious about decarbonization & localizing supply chains – all that requires a lot of new infrastructure) and a constrained supply (investment has been decreasing in these sectors since capital chased sexier ideas such as the metaverse & buy-now-pay-later schemes).

Think about it: electrifying everything and installing renewables is going to need A LOT of copper, silver, lithium, cobalt, nickel, etc.; similarly, if fossil fuels are going to get scarcer but countries are still vary of renewables, could they turn back to nuclear?

Maybe the countries that have and export these commodities might be worth looking at (one of them is a favorite to win the FIFA WC 2022!)

[This is a great read on the energy sector specifically]

Ratio of the S&P 500 index and commodities

Comparison of low-inflation and high-inflation regimes

Source: Prometheus Research

[Note: this is a hypothesis, not investment advice. Commodities also get hit during a recession when demand goes down. It depends on your time horizon. There is also a wide array of commodities, each with its own market dynamics]

Why this matters

Financial markets have a symbiotic relationship with the real world, especially given the degree of financialization over the past few decades. This isn’t just about becoming rich through investing; its also about preserving your wealth in uncertain periods and surviving the impact on the real economy.

Jobs: For example, think about how essential stock-based compensation has been to attracting talent to Silicon Valley. All the smartest people rushed to join startups and accepted median salaries with limited job security with the hope that their equity in the company would make them a millionaire rather quickly. Same is true for people joining big tech as well. But what happens when those stocks are going down?

Another way to think about it is what happens to these high-growth companies hiring thousands of people every year when their stocks are down 70-80% (e.g. Facebook & Netflix). The recent wave of tech lay-offs shows the real-world repercussions.

In fact, unemployment and the stock market have had a close relationship for a while – i.e. unemployment is forced higher (through raising interest rates for example which crushed demand) before the stock market reaches its bottom. And look at where unemployment is right now!

I could make a similar point about recessions. Arguably, the worst is yet to come on that front.

Figure 9: S&P 500 Index comapred to the US unemployment rate

(You can see that in the past 2 bear markets, the stock market — blue — reached its bottom only when unemployment — orange — had surged to its highs)

Wealth: Going to repeat the earlier cliché here – they say you can’t save your way to retirement, you can only invest your way there. And again, in a financialized world, what’s the alternative. Even pension funds are engaged in massive risk-taking, not just in major stocks but in startups (the Ontario Teacher’s pension fund, a leading investment fund btw, lost $95M on FTX; Denmark’s largest pension fund is down over 35% this year).

So when stocks go down or are flat, there are serious consequences. This is compounded by the fact that housing, which is the biggest source of people’s savings and collateral, also goes down with stocks, as is happening right now. Now imagine what happens if inflation stays at an average rate of 4-5%, meaning your cash is also losing value rapidly?

Afterthoughts

It is a huge shame that financial education is so underappreciated at all levels of our academic and professional journey, and when it does happen, it’s usually centered around narratives that might have worked over the past 20 years but aren’t meant to work forever. Market regimes change and I think more people need to be aware of the downside risk. The surge in zero-fee stock brokerages and availability of ETFs have made access to financial markets easier, but that has also meant increased risk as more money has poured into these markets.

The era of making easy money may be over. Passive investing may not yield the same 5-7% of annual returns anymore. Wealth destruction may become a more frequent occurrence than we have become used to.

It’s likely not going to go in one direction of course – in keeping with the theme of my writing, I think the only thing to be reasonably sure of is volatility. 2023 might be a relatively good year for financial markets, but that will just compound the risks. This is exacerbated by, in my opinion, a dopamine-addicted generation that has access to financial markets on their fingertips and rampant financialization.

Also, this piece was mostly focused on historical analogs to provide a sense of perspective. But a more compelling argument is to think about it from an economic fundamentals perspective, something I will cover properly in a future piece. In short though, we are at the tail-end of a multi-decade, even a century long, civilizational cycle. You can see that in terms of corporate & government indebtedness, all the geopolitical points I mentioned in newsletter #1, etc. Crises like that tend to be a lot harsher and a lot longer.

Something is different.

If you made it this far, here’s a funny clip from CNBC that epitomizes the type of investment environment we have been in:

Appendix

Valuations

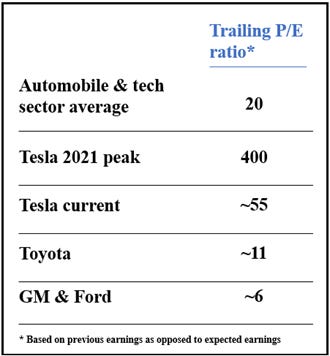

One quick and easy way to think about whether it’s a good time to buy a stock or not is by looking at its price-to-earnings ratio (PE ratio). It tells you whether the price of the stock has gone out of sync with the company’s earnings – this of course rests on the logic that a company’s worth is tied to how much profit it’s earning. This is a decent proxy for the valuation level of the company (i.e. is the stock at its current price overvalued or undervalued).

Let’s take tech stocks as an example since they have been the market favorites and are probably most known to people.

Nvidia: In many ways, Nvidia has epitomized the recent bull market. Both the company and the stock have been done really well prior to 2022, buoyed by the Covid-19 lockdown related surge in gaming and the increased demand through cryptocurrency mining (which uses GPU chips produced by Nvidia). It is also a well known and reputable company, with limited risk of it turning out to be a ponzi.

Yet, despite the stock being 65% down from its peak, the stock is arguably way overvalued. Even if the P/E ratio was to fall to a higher end of the average (~30), that’s a 50% fall in share price from here (check table below). And that’s assuming earnings stay constant – which doesn’t seem likely with a recession.

[This is not meant to be predictive, just directional]

Figure 10: Nvidia price chart

(log chart)

Figure 11: Nvidia P/E ratio

Another example is the darling of this market: Tesla. I will just leave the numbers and chart here for your imagination.

Also, the appendix has some good charts on the favorites of the dotcom bubble (e.g. Microsoft and Cisco – you can also check out IBM, Intel and Oracle online). All these are good companies still thriving today, and yet their stock prices really struggled for quite a long time.

Figure 12: Tesla stock price

(log chart)

[In my personal opinion, that Tesla charts look mighty scary if you look at some of the charts in the appendix]

Figure 13: Tesla P/E ratio

P.S. it’s not just tech stocks. Look at the P/E ratios of companies like McDonalds, Clorox, etc.

Interesting charts

Figure 14: Dotcom bubble giants (Microsoft + Cisco + Intel)

(These companies are thriving till this day and yet not only did their stock prices crash, they were flat for a decade or more!)

Figure 15: Modern day leading tech stocks (Meta + Shopify + Netflix + Docusign + Zoom)

(All companies we use & possibly love. And yet, even if you had somehow miraculously bought these stocks at the bottom of the March 2020 market crash, you’d be barely flat or even negative - and this is without adjusting for inflation!)

Figure 16: Chinese tech stocks (Alibaba + tech ETFs)

(Chinese stocks, especially Alibaba, have been global names for a while. But again, even if you had timed the March 2020 bottom, you’d be seriously in the red on these investments. Wealth destruction is a real thing!)

Figure 17: Monster Energy vs leading tech stocks

(Finally, my favorite fun fact chart. The stock for Monster energy drink has majorly outperformed even the high-flying tech stocks had you bought and held it over 20 years)

its pretty long imo

I have been thinking about the Norwegian pension found (The oil found). If the predictions of global warming from ExxonMobile in the 70s holds. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abk0063

This global warming will affect the economy drastically at some point. We are after all biological. https://climate.nasa.gov/explore/ask-nasa-climate/3151/too-hot-to-handle-how-climate-change-may-make-some-places-too-hot-to-live/

This affects livestock also.

The wealth accumulated in the Oil found will become gradually worthless after some point or is economics and the stockmarket so out of touch with the real world that it dosent matter?