#9. Extreme weather conditions, cascading risks, and complexity

The oceans, sea ice shelves, and air temperatures are leaving experts perplexed and worried. We all should be as well.

[Please subscribe, share with your networks, and provide feedback. For less curated content, follow me on Twitter!]

“A change in the weather is sufficient to recreate the world and ourselves.” — Marcel Proust

If you haven’t heard yet, there’s something crazy going on with the weather. And no, this is not just about having some city in South Asia or the Middle East break the temperature record.

I initially mentioned this in newsletter #7 as one of the top three things to be on the lookout for in 2023.

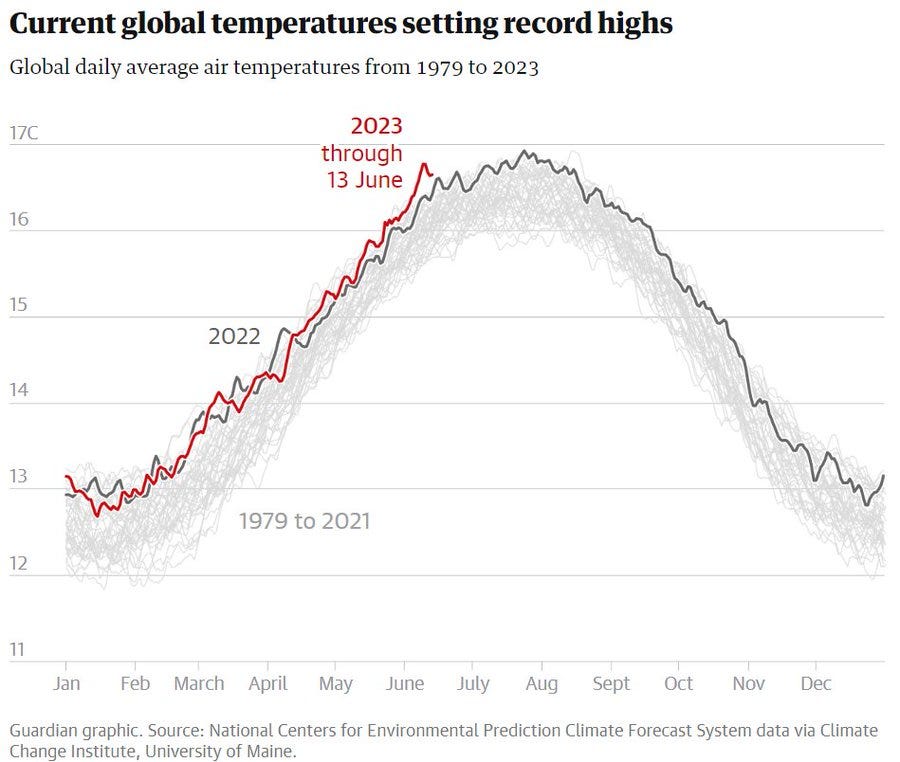

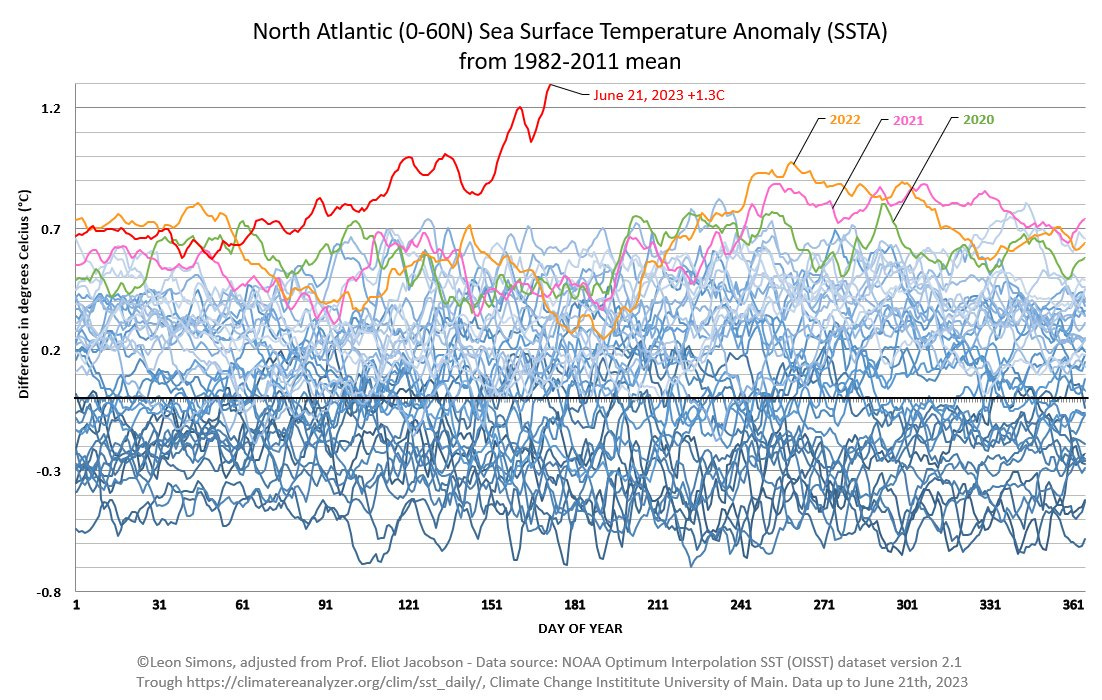

Here are three charts to relay what maybe thousands of words cannot.

Figure 1: Global temperatures breaking records across the board

Figure 2: Ocean temperatures are not just breaking records but literally going off the chart.

Figure 3: Staggeringly low sea ice in the Antarctic (and in fact globally).

2023 has been a year of extreme weather conditions, to the extent that even climate scientists — people who by this point are used to record breaking temperatures every other year — are perplexed.

“We’re seeing numbers that aren’t just off the charts, they’re off the wall the chart is tacked to.” — Bill McKibben

“This is totally bonkers and people who look at this stuff routinely can't believe their eyes. Something very weird is happening.” — Brian McNoldy

“Everything is happening so fast, it's hard to get a sense of the enormity of these anomalies, let alone their consequences.” — Eliot Jacobson

This piece delves deeper into this topic, focusing on 3 parts:

Brief explanation of what’s going on with the weather

Potential causes for these anomalous weather conditions

(Most importantly) How this impacts the global system & our everyday lives

It is important to make the climate vs. weather distinction here.

While the two are of course similar concepts with a temporal difference, the key point here is that the alarm bells in 2023 are not only ringing because of a change in the long-term (climate) trends (e.g. global warming, CO2 emissions, etc.) but because of extreme weather conditions happening as we speak.

So this is not about the future, this is about the present!

Here’s the summary:

The oceans are warming at an unprecedented, chart-shattering pace. This is bad because ocean’s trap heat which eventually gets released into the atmosphere.

Lots of feedback loops being activated (e.g. sea ice sheet melting means more heat absorption by water, leading to more sea ice melting)

Human-induced global warming is the main driver but a range of reasons, including the start of an El Nino cycle, are causing these extremities.

Serious impacts across 2023-24 at least, ranging from heatwaves, storms, droughts, food & energy crises, etc.

The weather is a complex system that is hard to model or control, and yet our actions and narratives are based on simplified frameworks and assumptions.

[I want to note at the outset here that this piece draws heavily from the work of people such as Leon Simons, Eliot Jacobson, Michael E. Mann, Peter Dynes, Jeff Berardelli and others. Highly recommend following them on Twitter to keep up to date & learn more]

Extreme weather (2023 edition and beyond)

The charts above highlight the basic problem:

This year is seeing a sudden and unexpected degree of warming in the oceans, particularly in the North Atlantic, along with record-breaking land temperatures and dangerously low levels of ice in the Antartic. All these are interconnected because the weather is a complex system.

The results of this have been the extreme weather conditions you may have heard about in the news, ranging from blazzing heatwaves in Texas, Mexico, the Middle East, West Africa, Southern Europe and South East Asia, severely warm winter temperatures in Southern Africa, massive wildfires in Canada, developing drought conditions in parts of the US, Europe, and South Asia, stronger than usual storms (including hail storms, flooding, tornadoes, etc.) in Guam, Myanmar, parts of the US and Uganda.

[I know I have almost nonchalantly listed these events but I want to emphasize the gravity of the risk posed, and damaged already caused, by each of these. We are talking about scores of adults and children dying, serious illnesses, loss of homes and property, etc., with the most vulnerable in society disproportionately affected.]

Figure 4: Extreme summer temperatures in the Northern hemisphere coupled with anbormally warm winters in the Southern hemisphere

Figure 5: The scale of wildfires in Canada has been unprecedented

While the wildfires and their impact on NYC have fallen out of the newscycle, the threat is not over and the smoke is now crossing over towards Western Europe while Chicago has the worst air quality in the world these days. The illustration below shows how interconnected and complex our weather systems are globally.

Figure 6: Wildfire smoke from Canada crossing over to Western Europe

Source: Nahel Belgherze

And this list is only of recent weather events — anomalous activity has been happening right since the start of 2023. Here’s a list of select extreme weather events this year.

Now let’s look at why the ocean warming in particular is causing climate scientists such distress.

Up to 90% of the global warming that has occurred over the past 50 years has been absorbed by the oceans. This is because water has a higher heat capacity than air and the oceans cover 70% of Earth’s surface area. However, the heat does not stay in the oceans; through various phenomena, this heat gets released back into the atmosphere, ultimately causing air and land temperatures to rise.

For example, there is increased evaporation with higher ocean temperatures. This transfers heat into the atmosphere, increases humidity, and traps more heat as the increased water vapor is a greenhouse gas. This also increases the likelihood of serious storms as there is more water in the air and the warmer air temperature allows for more energy to be carried. Hence, more rain, stronger winds, more thunder, etc.

Other methods include melting ice shelves, lower CO2 storage capacity of the oceans (which creates a positive feedback loop with more CO2 in the air —> more heating), direct heat exchange with the air, etc.

Basically, the oceans act as a giant store of heat, gradually releasing it over time. This protects us from feeling the full force of global warming initially but also means that the effects linger for longer and get distributed across the Earth by the ocean current system. So all the extreme weather events mentioned above are happening while the oceans are still heating up — the latent impact on land and air temperatures is still to be felt!

“In the heat of the sun, the ocean is the boiler and condenser of a gigantic steam engine, a weather engine that governs crops, floods, droughts, frosts, hurricanes.” — Jacques-Yves Cousteau

For those more quantitatively inclined, I found this back-of-the-envelope calculation to be hauntingly fascinating. That’s a lot of energy that is currently heating up (read: being stored in) just the North Atlantic Ocean — this will get released one way or another over the next 6-24 months.

The situation with low levels of global sea ice, particularly in the Antartic (for now), also raises alarm bells because of the feedback loop it spurs. Ice sheets reflect heat while water absorbs it; therefore, more sea ice melting means more heat absorbed by the Earth, causing more melting of the ice sheets and so on. I don’t want to get into the whole spiel about rising sea levels and all that since this piece is about the weather (near-term impacts) but sea ice plays critical roles in ocean circulation and regulating land + air temperatures. It’s melting negatively impacts extreme weather conditions, storm formations, etc.

So in summary, we are already seeing extreme weather conditions this year. But even more worryingly, the increased ocean heat & low levels of sea ice pose tremendous risks for more extreme temperature (think deadly heatwaves) and catastrophic weather events (incl. storms, floods, droughts, wildfires, etc.) not just this year but in 2024 and beyond.

Potential causes

There is significant debate going on the scientific community about what could be causing this unexepctedly rapid warming. Before climate-deniers jump on this, there is no debate about the fact that greenhouse gas emissions are the macro cause — the debate is about what exacerbating factors are compounding GHG-induced global warming.

Let me quickly summarize 3 causes being discussed.

1. Transitioning from a La Nina to an El Nino:

These are two naturally occuring climate phenomena that occur primarily in the Pacific ocean, affecting the surface temperature of the ocean, which then impacts the weather globally through changes in the jet stream, ocean currents, etc. Remember, small changes in the weather system in one corner of the world results in cascading impacts everywhere. Rainfall patterns, global temperatures, etc. all change effected by this.

Figure 7: How La Nina & El Nino work

Figure 8: Global temperature anomalies in La Nina & El Nino years

La Nina years are typically cooler and wetter while El Nino years are warmer and dryer. These phenomena usually last ~1 year, occuring every 3-5 years. However, we have been in a La Nina event for the past 3 years. One example of the impact can be seen in the extreme winter temperatures seen in central and southern US, resulting from a weaker jet stream that usually keeps cold air in the Northern part of North America.

In 2023, we seem to be moving from a La Nina (cooling impact) to an El Nino (warming impact). While these are natural cycles, global warming is making the impact of these more severe and unpredictable.

Figure 9: Change in seasonal weather relative to normal years

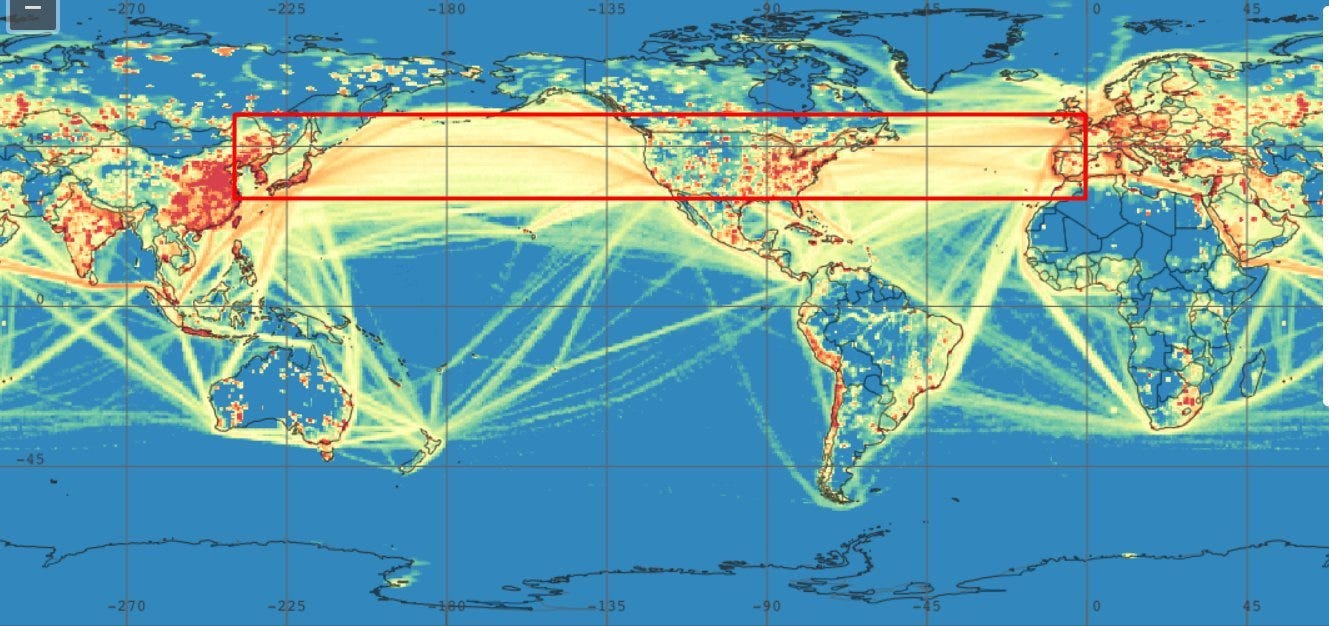

2. De-sulpharization and reduced air pollution:

This may come as a surprise but air pollutants, particularly particles such as sulphur and nitrogen oxides, actually have a cooling impact and counter global warming. At the same time, these are also of course toxic pollutants with severely dangerous impacts on human and ecological health.

In short, these particles are released through fossil fuel burning. Then, through various chemical reactions in the air to create aerosols, they result in increasing cloud cover which reflects more heat away from the Earth. Over the past few decades, and ramping up over the past few years, desulpharization has been a major policy achievement in order to counter air pollution. The flipside of that has been, almost in a greek tragedy sense, that the cooling effect of these pollutants has been neutralized, leading to more warming.

In particular, the desulpharization of fuels for ships has led to reduced sulphur emissions over the oceans, potentially exacerbating ocean warming through reduced cooling. To add to the complexity, the scrubbers used for this process on ships create acidic waste water that is simply thrown into the ocean, creating ecological damage on its own.

You can see the effect below — the red band is where most of the shipping routes are.

Figure 10: Global shipping routes & sulphur dioxide emissions areas

Figure 11: Correlation between sulphur dioxide emissions & solar radiation absorption

This is a major conundrum not just for ocean warming but also more generally. Desulphurization in coal power plants, oil refineries, and shipping fuels is necessary to counter air pollution but will lead to more global warming impacts. Look at the case of India for example — stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Figure 12: India’s deadly air pollution acts as a blanket against warming

3. Other natural events (e.g. reduced Sahara desert dust, Hunga-Tonga volcano eruption, etc.):

~180 million tons of dust get kicked up into the atmosphere every year and get carried over the North Atlantic ocean by winds, resulting in cooling effect as the dust reflect heat from the Sun. For multiple reasons, one of which is weakened and change wind systems, the Saharan dust has not made it to the atmosphere above the North Atlantic, thereby contributing to ocean warming.

Figure 13: Reduced Saharan Desert dust in 2023

The eruption of the Hunga-Tonga Volcano in 2022 has also potentially contributed to the increased warming this year. As with a typical volcanic eruption, suphur dioxide was released into the atmosphere but the quantity, and hence cooling effect, was lower than average. Instead, because this was an underwater volcano, huge amounts of water vapor was released. The amount is estimated to be ~140 megatons shot up straight into the stratosphere (~40km above the ground). This increased the water vapor content by 10-15% of that layer.

To summarize, the takeaway from these potential causes for all us, regardless of our interest in the science, should be recognizing the complexity of weather systems. This means that our ability to sufficiently model and predict is limited, as anomalous events can lead to serious multiplicative risks, and that human-activity (i.e. global warming) is disrupting a system that is hard to control. Those relying on incrementalism and future technologies are playing a dangerous game.

Impacts on the global system

“This El Niño will likely be costly to the global economy. The one in 1997-98, one of the most powerful in history, led to $5.7 trillion in income losses in countries around the world according to a study published earlier this month in the journal Science. It was also blamed for contributing to 23,000 deaths as storms and floods amped up in its wake.” — Umair Irfan (Vox)

It should come as no surprise that the weather impacts every facet of our life. From the potentially deadly health impacts of heatwaves and damage caused by storms to the second degree effects resulting from changes to agriculture, energy systems, supply chains, etc., there is no way to escape the disruptions that have already, and may continue to, arise.

An El Nino year is already bad (we are only in the early innings of one); the combination of everything else described above, along with decades of climate change, will make it worse.

Here I am intentionally going to avoid the more climate-related impacts of this warming (coral reef loss, change to marine life, etc.) and just present a select range of more immediate and tangible — in the short run — impacts:

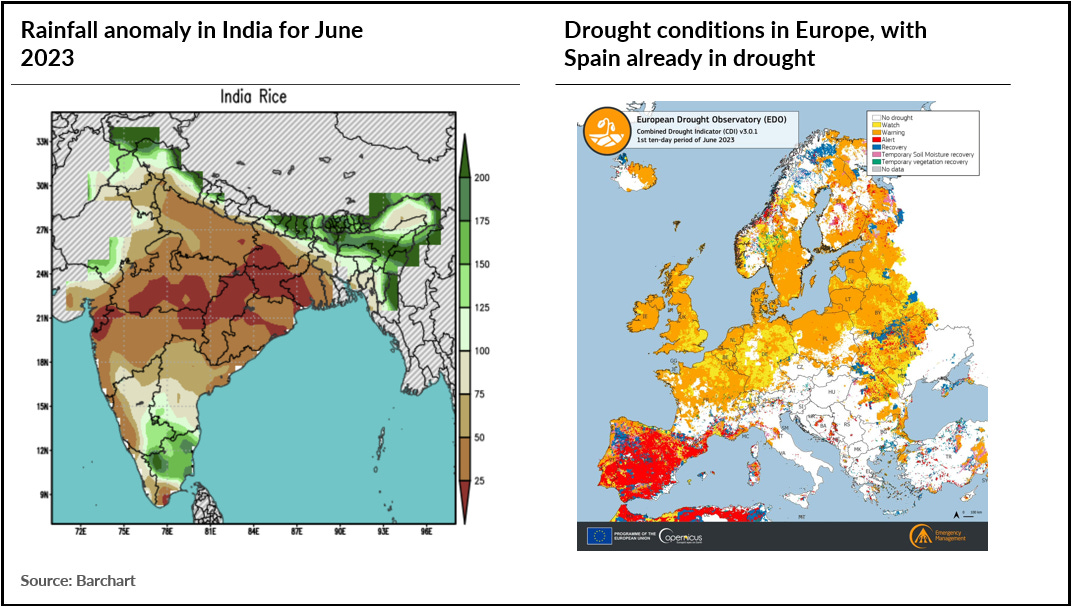

Damage to food production: Drought conditions are already present in many parts of the world and expected to get worse in 2023 and into 2024. The Horn of Africa is already facing the worst drought in 40 years, impacting 20 million people. Same for other parts of the world, including South Asia, Europe, etc. These issues are in no way local. While the poor and most vulnerable in these regions suffer the first degree impacts, the damage ripples through the global system by putting strains on food production, potentially leading to shortages and price spikes.

Figure 14: Drought conditions in India and Europe

Damage to energy infrastructure & decarbonization efforts: There are multiple ways in which the energy infrastructure comes under stress and/or suffers serious damage. For example, increased demand for cooling in heatwaves putting more strain on electricity generators, transmission lines, transformers, etc., leading to blackouts. Storms do that too by directly damage the infrastructure.

“Baseball-sized hail took out a solar farm in Scottsbluff, Nebraska… He [Nebraska Public Power District representative] said the panels are designed to withstand hail, but the size of the hail Friday was exceptional.” — Source

Figure 15: US electricity grid risk assessment 2023

Source: EIA In many cases, countries may have to increase fossil fuel consumption to meet the increased energy demands and also because renewable energy faces efficiency losses during high heat. For example, the efficiency of solar panels reduces at higher temperatures, ultimately needing to be turned off to avoid damage. Nuclear power requires copious amounts of cool water; when this is not available, as was evidenced in France last year due to high temperature of river water, the nuclear stations have to shut down.

So here’s another feedback loop: global warming —> more fossil fuel use

—> more global warming.

This then has the knock-on effect of increasing prices for fossil fuels, leading to richer countries like Germany pricing out poor ones like Pakistan and Bangladesh, which is what happened post the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Higher natural gas costs also lead to higher fertilizer prices, which can exacerbate an already strained food production situation.

Supply chain & infrastructure damage: All the weather patterns discussed in this piece lead to more and worse storms. This can have relatively smaller impacts like increased turbulence during flights (which can still cause serious injury) to larger impacts like hurricanes and cyclones that decimate homes, roads, factories, etc.

Just think about the impacts the Canadian wildfires have had by not just damaging ecosystems (oh and by also releasing CO2, which is another feedback loop) but by dangerous levels of air pollution in Canada, the US east coast, now potentially Western Europe.

Similarly, we are all well aware of the catastrophic damage that extreme weather events, such as the floods in Pakistan, can cause and how long it can take to recover (many regions do not recover).

All this is on top of the existing crises, some of which I have talked about in previous pieces: social unrest, economic crises, long-term climate impacts, etc.

Finally, I want to emphasize here that, as with all other things, the burden of this is borne by the most vulnerable and exploited people in society, both within countries (e.g. rich people can afford to stay indoors and have ACs) and between countries (e.g. Global South countries lacking the material and financial resources to invest in mitigation, disaster management, and recovery).

This is inextricable from growing social unrest and geopolitical risk. Feedback loops are everywhere.

Conclusion

On the one hand, the mainstream climate narrative pretends that we are in the 1980s, meaning that we have time to experiment and wait for technological solutions. The severity of impact is already happening now, as is clearly evidenced. The narrative also is predicated on the belief that humans can control the natural system we live in. Again, as evidenced by this piece, we live in a complex system where small changes that have major, non-linear impacts, and where the causal relations between factors is circular, intricate, and too complicated for us to sufficiently model, not to mention control.

On the other hand, we have the very real challenges of energy security, development shocks, and geopolitical risk. Tackling those is often at odds with other goals (e.g. reducing air pollution is a health prerogative but increases global warming or that heatwaves warrant the use of whatever energy source is available to protect people).

I am not going to pretend that I can offer a solution here (although in future pieces I will build up to my opinion of what needs to be done); instead, I hope we can build our analyses, debates, and proposals on a real understanding of the world. Wishing complexities away just because it supports desire to somehow maintain the status quo or have it all is ultimately self-defeating.

To repeat a line I love to quote: “In the war between physics and platitudes, physics always wins (eventually).”

Resources

Thread on radiative forcing and cumulative energy

Very comprehensive! Starting to take interest in climate change conversations, clean-tech solutions and environmental impact brought about by our lifestyles, and so this was a great (but worrying) read. Thanks Taimur.