#2: Understanding Energy

To understand everything else, follow the molecules. You can't print them.

[Author’s note: Thank you for the great response to the first piece. I hope this will provide some learning as well. Please subscribe + share + provide feedback — help the community grow!

I also have a poll at the end to help get some specific feedback + a section for resrouces + a short glossary — check it out.

Follow me on Twitter!]

In the first newsletter, I gave a high-level explanation about the fractures in the global system. With this piece, I want to dive into one of those fractures, something that underpins the whole system: energy. Whether it is because of climate change, electricity outages, or high oil prices, energy is becoming an increasingly mainstream part of the discourse. And yet, I would argue that these conversations either underplay or completely miss many important nuances about energy. We need to shift from “follow the money” to “follow the energy”.

Here's the summary:

Human civilization and progress are all about creating order (stable temperature, stable supply of food, etc.) The only way to do that is to consume energy. That is the base layer, everything else – labor & capital – come on top of it.

Our primary energy consumption has been surging higher; we have never had an “energy transition” as we have consumed more of each resource throughout history.

All energy resources are not the same (1 Joule /= 1 Joule). We must think about energy quality: density, energy return on investment, and reliability.

“In the war between platitudes and physics, physics always wins” – Twitterverse.

So let’s learn some physics! (admittedly not the most inviting pitch)

Energy is civilization

Anyone who has been exposed to economics, finance, or the world of business probably frames macro-scale choices using two overarching ideas:

- Financial affordability defines what is feasible versus what isn’t

- Labor, capital (machines, land, etc.), and technology (doing more with less) are what drive production

The objective of this piece is to bring attention to the primacy of energy, how it is the foundation of everything, and how energy blind we are.

Here’s how to think about it: let’s consider the evolution of human civilization. When we talk about progress and having a higher quality of life, we are basically talking about how we produce and consume more than before. This applies across a spectrum of essential services to discretionary consumption:

Heating and cooling our physical spaces to feed our desire for thermal stability;

Creating fertilizer for food production

Transporting people and goods across cities/countries/continents

Building new homes, schools, hospitals, and stadiums

Buying off-season, chopped and packaged South Asian mangoes at Walmart;

Flying for a weekend getaway.

If this sounds somewhat abstract, let’s think more micro.

We see perfectly chiseled, flat surfaces around us all the time. The room you are reading this in probably has straight walls and (near) perfect right-angled corners.

In other words, what we have around us is order. Another way to talk about the progress of the human species is its increasing ability to impose order in the natural world.

Order does not only have to be imposed, it needs to be maintained as well. Nature is spontaneous and volatile, and essentially our whole life revolves around countering that.

The only way to create and maintain this order, and hence make progress, is through the use of energy. This is the second law of thermodynamics as well.

For example, it takes energy to mine and process sand to create ceramics, which is a material that is widely used in our everyday life. The spontaneity of nature means that your ceramic bowl can shatter in an instant – sudden reversal from order to disorder. Can you put it back to exactly how it was? Probably not. All that energy was used to create order temporarily, followed by more energy use to replace the old bowl with a new one.

I hope those examples illustrate how integral energy is to our civilization. It is not yet another “factor of production” the way economists would frame it, it is the source of life.

“Labor without energy is a corpse, capital (machinery) without energy is a sculpture” – Steve Keen

Therefore, all of finance is basically an abstract system built on top off, and to regulate, flows of energy. Labor, capital and technology are all ways to access and convert energy. Energy is the underlying enabler of the whole system, and yet when we evaluate decisions in the present or plan for the future, we often don’t think about energy beyond it being a cost item on the balance sheet.

Development is an outcome of energy consumption

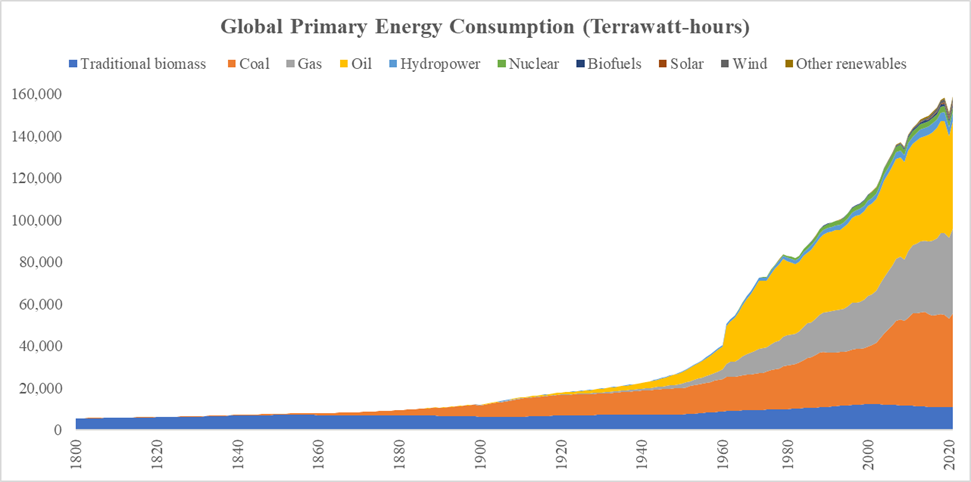

The best evidence for the aforementioned spiel is to just look at global primary energy consumption. Our centuries of progress have come out of an extraordinary increase in this metric. Another way to look at it is also energy use per capita – since one could make the argument that you can increase total consumption through just population increase – and that has also been surging higher, particularly since the 1950s (chart in appendix).

Figure 1: Primary energy consumption has surged higher

Source: Our World in Data

There are two interesting things to note here, both with serious consequences in terms of how we think about energy use:

We have never seen anything called an “energy transition”. Mainstream discourse often throws around this concept that we moved from wood (biomass) to coal to O&G, and so the next evolution is just moving towards renewables. But as the data shows, we actually never moved from one source to another, we simply piled on top.

For the most part, we have used more of each energy source year after year. I want to explicitly call out here that a lot of the narrative around renewables focuses on the % of energy coming from solar + wind, and while that is relevant for certain conversations, it’s not the appropriate way to think about our energy dependence or the climate impact. Both those concepts care only about absolute energy consumption.

There is only a small blip in consumption in 2020. I say small because the blip took us back to energy consumption from barely a few years ago and it rebounded sharply in 2021. I encourage you to stop and think about this for a moment. We had mass Covid-19 lockdowns virtually everywhere around the world: travel, particularly the energy intensive forms such as aviation, was severely limited; people were doing everything at home so offices and malls were closed; supply chains were constrained so there were less goods moving around. We basically implemented an extreme curtailment of normal activity and yet the impact on energy consumption was arguably minimal. That is how embedded, particularly in non-obvious ways, energy consumption is into the global system.

[Note: The aviation point regarding the Covid-19 lockdown is interesting because even though many people weren’t flying, airlines were flying around empty planes just so that they could maintain their slots at airports – sheer insanity. This is a great sign of how energy blind our decision-making is.

Both the points I mention have strong and quite underappreciated implications for the climate movement, but I will save that for a later piece.]

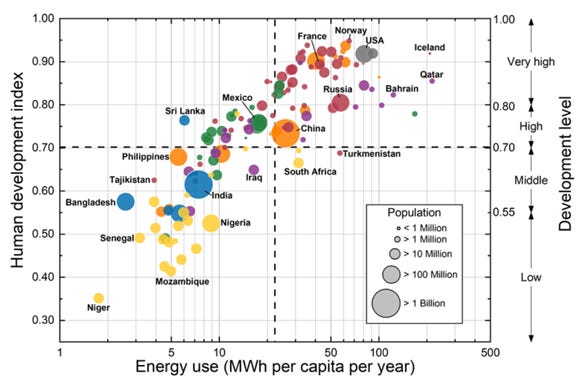

Figure 2: GDP and energy consumption are symbiotic

Source: Our World in Data; World Bank

Staying at the macro-level, let’s also look at the relationship between energy consumption and some metrics of progress. The fundamental goal of our economic system for the past ~100 years has been achieving GDP growth, which has a near perfect relationship with energy consumption (Figure 2 above). This is also true when looking at the relationship between the Human Development Index and energy per capita (Figure 3).

This is true not just across time but also across countries, where highly developed countries also consume significantly more energy. It is grossly misleading when people, even scholars and analysts, evaluate the importance of the “energy sector” based on the industry’s contribution to GDP (which is 4-5%) while not recognizing that energy is what drives every other sector as well.

[Take for example Germany this year, a highly advanced and developed economy but also dependent on Russian natural gas. ~13% of Germany’s energy mix was made up this one source, for which it was paying ~$20 billion. Using this cheap and effective energy source, estimates suggest that Germany was able to create $2 trillion of value (goods & services). That is 100x “leverage”! Take away that cheap gas away and, as Germany has realized as it has faced gas rationing and deindustrialization, the adverse effects are multiplicative and widespread.]

Therefore, I hope at this point the inextricable relationship between any form of growth or development – at least given the economic structure we have been living in – and increased primary energy consumption is evident and intuitive.

It is easy to get lost in narratives that use abstract concepts such as political systems and economic incentives to explain the past 100 years; while I am not denying their role, I hope to press upon the point that those concepts build on top off what the real world – the physical world – allows, and that energy is the driver of that reality.

I would also take a moment here to reflect on these charts and think about how ~750 million today are without sufficient food, 150 million people are homeless with an additional 1.6 billion living in inadequate shelter, and ~700 million people are without access to electricity. This is a fundamental failure of development and filling this gap will require a tremendous amount of more primary energy consumption.

Figure 3: Developed countries consume substantially more energy per capita

[The x-axis is not uniform so small changes actually reflect significant differences. For example, Norway consumes ~12x more energy per capita than Sri Lanka]

Source: Fischer, 2018

Our energy superorganism

Nate Hagens argues that our current system is essentially an “energy superorganism”. I like that label because it is an effective way to think about both how deeply dependent the system is on energy and the tremendous scale at which this system works.

Despite the conceptual and empirical data I presented above, it can be hard to truly appreciate just how much energy we consume. So let me try some ways to make that intuitive.

The point of energy is to “do work”. Labor is one way to use energy (energy from the sun is stored in plants & animals —> consumed by humans used to do work).

So let’s put our primary energy consumption into human labor years for a sense of scale. Doing some quick math shows that our annual energy consumption is equivalent to having 420 billion humans working for a year. That’s how many people it would take to replace our energy use!

[This is of course a rough, speculative form of math meant to show a sense of scale, not be accurate]

Source: Hagens, 2020; Our World in Data

I think a common energy related concept that we all can relate to is nuclear energy, particularly nuclear weapons. Intuitively we know that there is an incredible amount of energy packed into a small space which is what makes those weapons so apocalyptic.

So how does that compare to our energy use? An average oil tanker (carrying ~2 million barrels of oil) has the roughly the same amount of energy as a large nuclear weapon!

Another way to think about it is in terms of aviation. Just in the US alone, there are ~45,000 flights *daily*. The jet fuel consumption of these flights is slightly more than 2 million barrels – every single day, just in the US!

This of course only looks at the energy consumed while the plane is flying and does not include the tremendous amount of energy used to extract the raw materials, manufacture the plane, maintain it, transport it, etc.

So two main takeaways till this point: growth & scale. Our energy consumption has been, and is, rapidly increasing; the amount of energy we consume, even if we were to stop today, is astronomical. There’s nothing good or bad about either of these points, it’s just meant to assert the critical importance and embeddedness of energy in every fabric of our society.

High on hydrocarbons

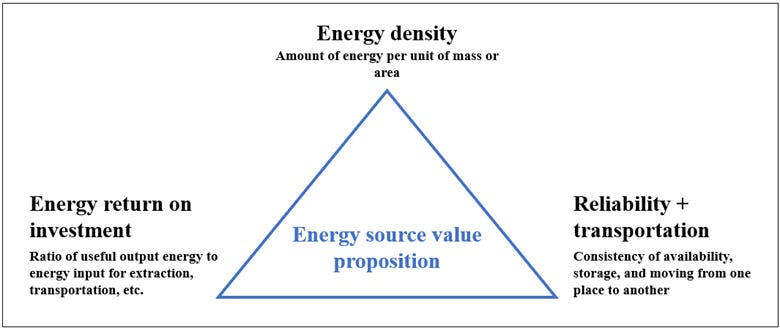

Here I want to circle back to the conceptual point about energy = order = progress I made at the start and add a little more nuance. It is not just increased energy consumption that has driven this relationship but improvement in the quality of energy. Looking at it purely from an energy perspective (i.e. leaving out cost, environmental impact, etc.), an energy source can be evaluated across 3 features:

[A little science 101 recap. Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it simply gets converted from one form to another. And all energy on Earth comes from the Sun. Fossil fuels are just stored solar energy packed into tight spaces over millions of years of high heat and pressure]

1. Energy density

The concentration of high amounts of energy in small pockets, measured in terms of weight or area, has unlocked amazing use-cases for our society. Think about airplanes and heavy industrial processes (e.g. making steel or cement). These technologies require an incredible amount of energy with low weight (to fly) and low surface area (in factories). As we have consumed more energy over time, we have also moved from low to high energy density sources. Now it is potentially going to be in reverse. Moving towards renewables will require a lot more land-use area and potentially make things heavier (for example, batteries in EVs are considerably heavier — although other parts of the EV are lighter).

Figure 4: Power density of energy sources

[note: logarithmic x-axis so the differences are order or magnitude]

Source: Zalk & Behrens, 2018

2. Energy return on investment

The whole point of our civilization has been to do more with less. For that to happen, we have needed more surplus energy – meaning energy leftover after we re-invest energy to extract more of it. You can imagine a world where absolute energy consumption is going up, but if a greater % of that energy is simply being used to access and use energy, then there’s less “surplus” energy left for us to use for other things.

Figure 5: Energy extraction to end-use

[EROIfin: extraction to final consumption; EROIprim: output vs input at point of extraction]

Source: Brockway et. al, 2019

A simple analogy for this is that centuries ago, most of human energy was spent growing food and achieving sustenance. Hours were spent farming or rearing livestock, and a lot of that produce was then consumed to survive and keep this cycle going. Now we collectively spend drastically less energy on activities that achieve sustenance, meaning we have more energy left to “make progress”. All the luxuries of life, whether in terms of materials goods or in terms of art & culture, are possible because of relatively high EROI.

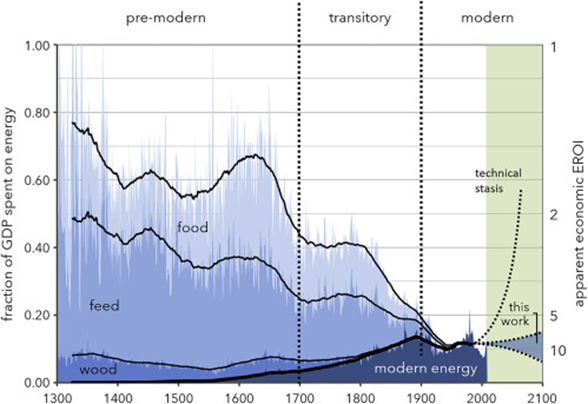

Figure 6: Evolution of EROI over the past millennium

[Left y-axis shows decreasing % of GDP spent on food, animal feed and heating while right y-axis shows improving EROI. Basically having more energy surplus means we spend less resources on necessities]

Source: White & Kramer, 2019

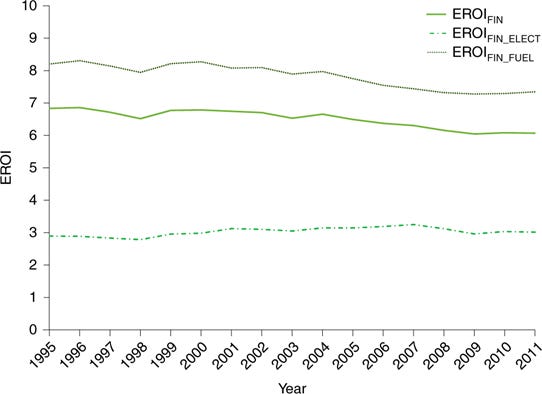

The important takeaway is that as we increased energy consumption throughout the 20th century, we were also moving from low to high EROI (some estimates suggest the mid-20th century had an EROI of 30-50:1). That means for every 1 unit of energy invested, 30-50 units of energy were returned. For the past few decades, that return has been going down for hydrocarbons – we have had to use more energy to extract and use these resources (Figure 7). For example, the past 10 years saw an arguably “artificial” boom in oil & gas supply as fracking in the US took off. But fracking is technically harder, requires more energy, and is more expensive (ignoring the socio-ecological impacts).

[Fracking: A process that uses high-pressure to fracture deep rock formations to access “tight” oil, with natural gas a co-product.]

Figure 7: Changing EROI for fossil fuels

[Even though the changes seem small, they correspond to a ~10% decline which is significant given the importance of energy surplus. Also, as we move closer to 1, the marginal impact of these declines exponentially increases – also known as the “energy cliff” (great chart in the Appendix)]

Source: Brockway et. al, 2019

The encouraging sign is that the EROI for renewables is now comparable (estimated at 5-20:1) and potentially improving. Regardless, it is still part of a long-term secular decline in EROI for the energy system overall as renewables will not be able to replace hydrocarbons for specific energy-intensive processes (so we will have to deal with the falling hydrocarbon EROI) and renewables will likely not be able to reach the 20th century peak.

3. Reliability + transportation

I won’t go into much detail here because these concepts are more widely talked about but the gist of it is that hydrocarbons, particularly oil, are relatively easy to store and move around globally. The past 2 decades have also seen major investments in the infrastructure to globally transport natural gas (the big push recently is infrastructure between the US and Europe to decrease reliance on Russian gas).

Renewable energy, however, needs to be transported as electricity which requires major investments in transmission infrastructure (notoriously difficult both politically and socially) and faces technical challenges to how much power can be passed through transmission lines.

On the reliability side, hydrocarbons are always ready to go, easy to switch on-off, and can be scaled up and down to meet demand. Renewables face the problem of intermittency (when the Sun is not shining or the wind is not blowing), it is harder to adjust supply to match demand (making flexible demand more important), and storage is much more complicated.

I don’t want to fall into the anti-renewable energy narrative trap here though – there are a lot of technologies and smart solutions to these problems. However, implementing them at scale is costly, challenging, and requires a fundamental reorientation of the electricity grid and overall energy system (which of course we must do for climate reasons).

Why this matters

Thinking of this purely from an energy perspective, it is important to recognize that these facts don’t necessarily lend credence to any particular political or policy agenda.

My intention is to simply make clear that regardless of what type of system we see next, it will look fundamentally different from today, and that will have tectonic implications on society and how we live.

Let me leave you with 3 (of many) implications:

Development and energy go hand-in-hand: Much of the Global South consumes way too few resources to achieve a reasonable standard of living. Here I am not talking about just conspicuous consumption and fast fashion but access to food, shelter, electricity, heating, technology, etc. Since all of these needs require real resources (i.e. can’t be fixed in the metaverse) and there are large swathes of the global population whose needs are unmet, this will require considerable energy.

Think in terms of energy: We are too used to thinking about everything in terms of financial costs. But prices and costs are easily distorted and are poor indicators of reality. For example, a decent dinner for 2 in Palo Alto will cost $80, which is the same price as a barrel of oil. Are those things truly comparable in terms of scarcity and usefulness though?

Anyways, we have to orient our thinking towards energy resources. If push comes to shove, we can always borrow money or not go into debt or any other such solution – what we can’t do is magically create energy. The Germany example from this year is an essential reminder of that.

Falling off the energy cliff will feed other crises: Perhaps for the first in history, we are moving downwards in terms of energy quality, agnostic of whether we decarbonize or not (although decarbonization will help!). And as I laid out in newsletter #1, many of our global crises are interconnected, with energy being central to many of them.

If energy becomes scarcer, then it too will become increasingly weaponized (as has happened this year first with Russia versus the EU and then with OPEC vs the US). Every country will want to keep/get the good stuff (hydrocarbons) for themselves. Global supply chains rely on cheap and readily available hydrocarbons too. So does the production of fertilizer, steel, and chemicals – the things that are, literally and metaphorically, the foundations of society.

Afterthoughts

I want to be clear about two things here.

Firstly, I intently tried to keep this objective and not share my own opinions about hydrocarbons and decarbonization (maybe I will cover those in a future piece but for now I share them on Twitter!). There are additional layers of complexity that I hope to cover in future pieces: metal & mineral mining, ecological collapse, etc.

Secondly, this was not meant to be predictive about what will happen. The goal is to add nuance to the current discourse and illustrate a general framework to help people think about present and future developments. This is because, as I mentioned in newsletter #1, energy crises are coming and will shape geopolitics and economics at least for this decade (see the Macron pivot towards Venezuela – the Biden admin has been making similar moves. Wonder what they need from Maduro after decades of sanctions).

All these concepts about absolute energy consumption, EROI, energy density, energy’s link with development, etc. are all just physical realities. Can we avoid an energy crisis? Sure, maybe. We have a plethora of choices and ultimately the future is what we make it. But let’s be real about what choices we actually have and what it will take to make them. Hopeful narratives and generalizations can often do the opposite.

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions”

Appendix

Figure 8: Increasing energy per capita consumption

Source: Our Finite World

Figure 9: “Net Energy” Cliff

[As EROI decreases, the drop in % of energy available for social use exponentially falls]

Resources

Steve Keen:

Glossary

Energy density: Amount of energy per unit of mass or area.

Energy surplus / Energy return on investment (EROI): Energy output relative to energy input.

Reliability: Availability and ease of deployment for energy resources (e.g. how quickly they can be switch on to deliver energy).

Energy cliff: Reduction in EROI over time with an exponential collapse as EROI becomes too low.

Great piece!! Would love love to hear your thoughts about what a "just energy transition" looks like for the African continent, and how continental leaders and the private sector should think about this. As an African myself, I do feel "some type of way" about the restriction to use "transitional fuels" such as natural gas, even though we haven't peaked in economic growth & we've contributed less than 5% of current CO2 emissions. We do care about the climate globally, but 600m of the 700m people without access to electricity are in sub-saharan africa - and access to climate financing on the continent to boost renewable energy hasn't been quite as smooth!

I personally feel like you have really done it all here. From using interestingly funny blips to these really entertaining cartoons, which you made I guess, you really knocked this out of the park! Good job! It was really fun to read this. Looking forward to more!