#15: The arcs of history

Polycrisis, historical cycles, and the opportunity to remake our world.

[This piece presents how history moves in cycles, ending with an analysis of Palestine, climate change, and Pakistan.

Side note: Here are links to recent threads on Pakistan and Muslim societies that could be interesting. For more frequent commentary and hot takes, follow us on X!

Also, output here has been slow (apologies for that) but hope to get pieces out on the following topics before the end of the year:

Understanding the ecological crisis; industrial policy (market vs the state); China; and complex systems.

As always, please like, comment, and share to spread this free content]

I. Introduction

“There is nothing more crucial, in this respect, than Gramsci's recognition that every crisis is also a moment of reconstruction; that there is no destruction which is not, also, reconstruction; that, historically nothing is dismantled without also attempting to put something new in its place; that every form of power not only excludes but produces something.” — Stuart Hall

In newsletter #14 we presented the 4 part thesis: 1) inequality and other crises ramp up to the point that the pitchforks start coming out; 2) right-wing forces replace the liberal elite and begin to undo whatever progress has been made; 3) the dying system doesn’t go down without a fight and partners with far-right forces; 4) technological breakthroughs like AI present both existential risks and opportunities while accelerating how quickly things unfold.

This has been the underlying premise behind the newsletter and has mostly played out well across multiple topics.

The past month saw strong performances by the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Le Penn in the EU parliament elections. In the French snap elections however, the leftist parties delivered a crushing blow to the far-right — remember, Italy already has a far-right government and the Netherlands was close to making one after the most recent election as well.

Either state investment-led platforms that target inequality or far-right rhetoric that villainizes immigrants and promises a return to some pure past — those are the two choices in the future as the liberal centrists lose support from all sides.

Across the pond, the US is already beginning to undo civil liberties such as abortion, offering immunity to presidents from civil and criminal charges, violently crush non-violent protests, etc.

Major financiers, energy companies, and governments are reneging on their climate commitments, even as heatwaves and extreme events continue to break records. We keep repeating that the climate movement, even with its limited progress and mega-hype, doesn’t see the train that is approaching head-on.

All this to say that clearly, the winds of change are upon us, carrying major, largely unsettling, changes even though the mainstream narrative remains aloof to it. Liberals continue to act surprised by these developments. Everything surprises them; maybe it’s time for them to rethink their approach to the world if they’re going to be wrong so often about so many things, and then force us to listen to their moral pandering.

[Always a good opportunity to plug in some Graeber]

But we digress.

The Stuart Hall quote above exemplifies the dialectic approach of Gramsci, Marx, Hegel, and even older thinkers such as Ibn Khaldun (more on this later). It is only through crisis and chaos that the opportunity for something new and better arises. But to shift the balance from threat to opportunity, we need people to recognize the gravity of the moment and accurately understand the forces at play. In newsletter #12, we took the ideological lens to explain polycrisis (or metacrisis) — in this piece, let’s take a big-picture historical approach.

Many schools of thought today use history to inform their analysis, but they often suffer from either recency bias — where they take too much of the present for granted — or misapply historical analogs.

Is this like the 1970s, with high inflation and energy shocks? Is this like the 1920s, with the rise of fascism and high inequality? Is this like the end of the Roman Empire, with oligarchic control of the state and an exorbitant amount of debt?

As Mark Twain said, “History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme”. It is perpetually futile to find a historical analogy that can fully encapsulate the complexity of civilization; instead, we must recognize that the present is a polyphony of multiple historical tunes.

What forces from the past are we dealing with today? How quickly does history move? What does this mean for future potentialities?

This isn’t just about politics. Social norms, religiosity, art, culture, business practices, etc. are all governed by historical cycles. From what professions will be popular to what nations will exist, and everything in between, is shaped by these forces.

All these questions are answered across 3 parts:

Understanding historical cycles

The robustness of progress

Explaining current events through this approach (examples used are ecological collapse, Palestine, and Pakistan)

Or you could skip this whole piece and just follow Kamala Harris’ mantra:

II. Historical rhythms

In newsletter #12 we talked about how every one of us has an ideology, whether we know it or not, because without one it’s not possible to make sense of the world. For those who do not explicitly know what their ideology is, odds are that they follow the liberal ideology (distinct from liberal politics) as that is the dominant one today.

That relates to history such that liberalism forces history into a linear, sequential chain of events. The present becomes an outcome of the most recent prior events. Rather than forces ebbing and flowing (e.g., colonialism), such events get “solved” and become irrelevant. It’s all very nicely delineated and packaged. In fact, if you read Steven Pinker, Francis Fukuyama, Jarrod Diamond, Yuval Hariri, and most other airport intellectuals, they tell the story of human history in this linear fashion — from hunter-gatherers to agriculture to cities to modern civilization. The reality, of course, didn’t play out that way (read Graeber & Wengrow).

Alternatively, Gramsci talks about the importance of analyzing current events by looking at the multiple historical rhythms that converge to create every moment. Rather than history progressing through discrete events, there are waves that reverberate over varying, and some quite long, periods of time. So for example, colonialism didn’t just end in the 20th century through the formation of “independent” nation-states, its effects live on in very real ways and continue to shape the present.

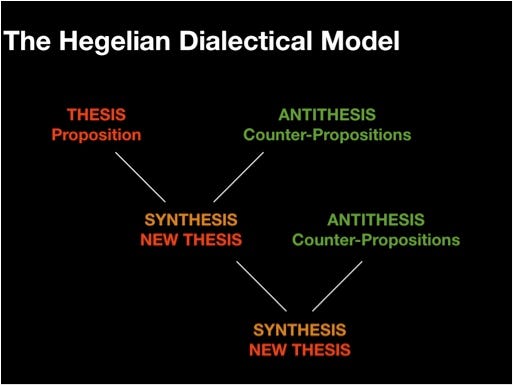

In other words, the present moment is not merely the result of the most recent prior moments, but a combination of forces from across various historical timeframes. We think it makes sense to see these forces as cycles of history, each with its own timeframe, strength, and features.

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” — Marx

This makes the argument more intuitive, as there is a sizeable group of people who talk about the end of the American empire, for example, simply as the completion of a historical cycle.

But let’s add more nuance and depth to this approach in a way that helps explain where we are today.

We can break these historical forces, or cycles, into 3 broad time frames:

Short-term: ~50-year cycles in which the more tactical facets of the global system change. This is the most surface-level form of the global system and hence is the most adept at quickly changing shape in the face of new forms of resistance, technology, etc. It is the mode through which the ideological goals and power relations of the system are represented.

For example, the US$ system was created ~50 years ago to maintain US global dominance in a world with rising oil-exporting countries, a global bout of economic development (led by South East Asia), etc. Before this, the US was still dominant but the mode was completely different, as the US was a trade surplus country, the US$ was pegged to gold, and the US was still funding the reconstruction of Europe. The creation of the Washington Consensus, the wave of privatization and deregulation, the quashing of unions and labor power, etc. can all be seen as short-term responses to the specific dynamics that have been relevant over the past ~50 years.

Medium-term: ~100-year cycles in which the foundation of the global system shifts, even though the underlying philosophical and metaphysical ideas remain the same. Two relevant examples of this are the American empire, which took over from the British roughly ~100 years ago, and the age of widespread fossil fuel use, without which modern civilization would be impossible.

Long-term: Multi-century cycles where the deep philosophical and metaphysical roots of civilization get shaped. For example, we live in the post-Enlightenment era today, regardless of where we live, which religious or ethnic group we belong to, and what we believe in. That does not mean that the Enlightenment is a monolithic philosophical system, or that we all agree with it — simply that everything around is shaped by it, even if it is in opposition to it.

Despite the diversity of thought, some core Enlightenment beliefs are the power of humans over nature, the need for rationality over spirituality, and the importance of the individual over the collective. Like it or not, these ideas run so deep that they literally shape everything around us. Both climate deniers and techno-utopian eco-modernists believe that humans can control nature; both liberal atheists and modern Muslims place the individual, rather than the social, at the center of their worldview; and all of us are united in our insatiable desire to fill the void of meaning in ourselves through conspicuous consumption and dopamine/adrenaline hits.

To be clear, this is not to hate on, or judge, any particular belief or idea. All ideas have their pros and cons. Many of these ideas have been part of other philosophical belief systems. However, the goal here is simply to articulate the context in which we live; the judgemental assessments depend on the topic, time, and place.

It is important to note some key things about this form of categorizing historical forces:

As we move from short, to medium, to long-term cycles, the gravity and robustness of the impact exponentially increase. This, almost definition then, also means that the inertia also increases, so the volatility and effort (read: resistance) it takes for a cycle to end exponentially increases.

These cycles operate as a complex system, meaning that it is virtually impossible, almost counterproductive, to use them predictively. The range of outcomes is infinite because of how various forces could overlap, how small events can change the trajectory of each, and external factors (e.g., nature) might play a role. The point is not to predict the future nor is it to trace a deterministic path through the past; instead, it is merely to understand the network of roots out of which the present has emerged.

For the sake of simplicity, this analysis condenses time and space. We assume that there is one, globalized cyclical pattern, and while that may be largely true under a unipolar hegemony, there is always a multiplicity of cycles and civilizations that exist.

The years mentioned against each cycle are adjusted to the present. Our increased ability to harness resources has led to increased globalization, which makes history go faster. Events reverberate across the globe quicker, a lot more violence can be inflicted in a fraction of the time, and more connection simply more fragility.

III. Where we are today

We are in the early innings of a cataclysmic transition as all three types of cycles are sunsetting while their replacements suffer from birth pangs.

In the short run, the era of neoliberalism is ending. The return of the state through industrial policy, tariffs, and increased global conflict has ended the Washington Consensus tactics of privatization and deregulation. Ideology has come roaring back as people realize that they have been kept under the veil of a post-ideological society, blinded by false promises of liberalism and forced into sterilized forms of resistance where any real criticism was branded as “radical”. The era of low interest rates and low inflation, at least in the Global North, is over as forces of secular inflation — demographics, supply chain disruptions, geopolitical risks, ecological destruction, etc. — become entrenched.

In the medium run, the American empire is ending. This isn’t a political statement because what made the US a superpower was its industrial might at a time when the world needed reconstruction after two world wars. Today, the country has crumbling infrastructure, an overly financialized economy, rampant inequality, extreme polarization, increasing sociopolitical violence, dwindling allies abroad, and weaker soft power globally. It takes decades, however, for an empire to arise; and hence, decades for one to end. If forced to make a prediction, we’d wager that a multipolar, regionalized global system follows, not a unipolar one with China.

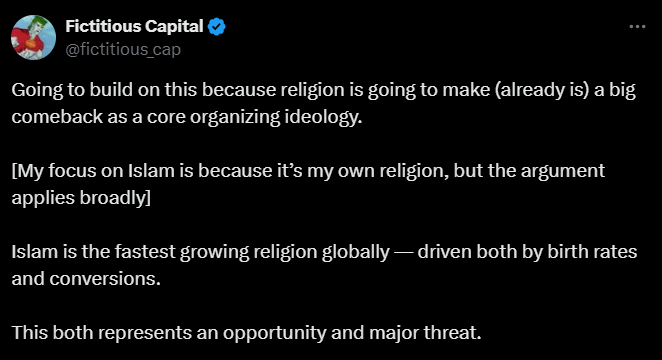

In the long run, the liberal secular atheist model of the world is gradually facing real competition. Increasingly fewer people believe that humans can definitively conquer nature and bend it to serve our needs. Prioritizing the individual over the collective, trying to solve all human needs, including spiritual and existential ones, through material consumption, and undermining non-Enlightenment traditions are all going out of fashion.

There is no question that these are still dominant ideas underpinning global culture, but they are withering away. The increased turn towards religion and spirituality, even including the exoticized versions of Buddhism, Taoism, yoga, etc., is an example of this change.

Others include more people seeking bucolic, slower lifestyles away from the hustle of urban cities, the recognition that the mental health epidemic cannot be solved through material stuff, and so on. Again, we should be careful not to assign some normative judgment to these trends because all lifestyles come with their pros and cons; their outcome in terms of social good depends on the context in which they are used.

“The world says: "You have needs — satisfy them. You have as much right as the rich and the mighty. Don't hesitate to satisfy your needs; indeed, expand your needs and demand more." This is the worldly doctrine of today. And they believe that this is freedom. The result for the rich is isolation and suicide, for the poor, envy and murder; for while the poor have been handed all these rights, they have not been given the means to enjoy them. Some claim that the world is gradually becoming united, that it will grow into a brotherly community as distances shrink and ideas are transmitted through the air. Alas, you must not believe that men can be united in this way. — Dostoevsky

But perhaps most importantly at this level is something we have talked about endlessly in this newsletter: the past few centuries have been shaped by unprecedented access to cheap and readily available fossil fuels and raw materials. We have constantly moved up the energy quality ladder (with oil at the summit), continuously consumed more and more of each energy resource, and plundered new sources of raw materials. The whole world, and our history, is shaped by this alone.

That era is quickly coming to an end. Even if we want to keep using more raw materials and fossil fuels, they are simply becoming harder to extract and use because we are rapidly depleting the easy-to-access, high-quality sources. This change alone will fundamentally make the next 50-100-200 years starkly different from the previous ones.

[More details on this here, here, and here.]

IV. The polycrisis

Before the case studies, it is worth briefly discussing how and why cycles end. Basically, how does history move forward?

The mainstream (liberal) approach is that bad things happen because people just don’t know any better, so through some education and public pressure, the people in charge have an epiphany that leads to progress. It may sound satirical but this is quite literally how liberals explain the rise of Western civilization: the world was barbaric and then a bunch of philosophers discovered “human rights” so that’s how women got rights, slavery was abolished, and the world was civilized. This is of course mere propaganda — it was then, to serve the slave-owning, imperialist class to which these philosophers belonged, and it is today.

Instead, there is the dialectical approach to history that we mentioned at the start. In this version, history progresses not from epiphany to epiphany, but as a repetitive process of creative destruction (to use a simplification). Every dynamic that arises, every system that takes root, simultaneously creates its antithesis. Therefore, at all times, contradictions are being developed and heightened in all systems. Ultimately, the contradictions become so severe that the system is forced into a solution where some essence from the old is maintained to create a new system.

Simply put, the liberal approach believes that bad things happen because something exogenous to the system went wrong — e.g., bad actors took power. It doesn’t recognize that what goes wrong comes from within the system. The dialectic approach, however, is more of a yin-yang model (to put it crudely) where the thesis and anti-thesis necessarily exist together — in fact, they create each other — and the contradiction between them is what drives historical change.

The important point here is that cycles don’t just end, they implode because of their contradictions. Violence, chaos, and volatility are standard features of this phase because those contradictions have led to pent-up energy — for example, an oppressed working class that has had enough — that is unleashed. The more cycles ending together, the more the intersection of this process, leading to a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” — Gramsci

This thesis, we believe, helps contextualize and explain the polycrisis. This is why the current era is not like the 1970s or the 1920s or whatever else. The latter is the closest analogy from recent history given that it too saw a short and medium-term cycle shift. However, the distinct differences are that European civilization was firmly hegemonic at that point and that long-term existential threats like ecological collapse weren’t dominant factors.

That’s what makes this era we are entering special because it is something that arises every few centuries. To reiterate, these changes take generations to play out, with a constant ebb and flow between trends and dynamics. What we do know is that, as this newsletter has made a point to note in almost every piece, is that volatility and uncertainty are the main themes.

There is a lot about the current world we take for granted, ranging from the existence of certain nation-states and the range of political possibilities to global supply chains and living energy-intensive (read: comfortable) lives. All that came into existence through past historical cycles, and so can easily — and likely will — get undone in this transition period.

The only thing real is the material world — i.e. physical constraints, the ecology, etc. Everything else is human creation, which is both liberating because the possibilities are endless if we expand our imaginations, but also terrifying because it reveals how fragile our way of life is.

V. Case studies

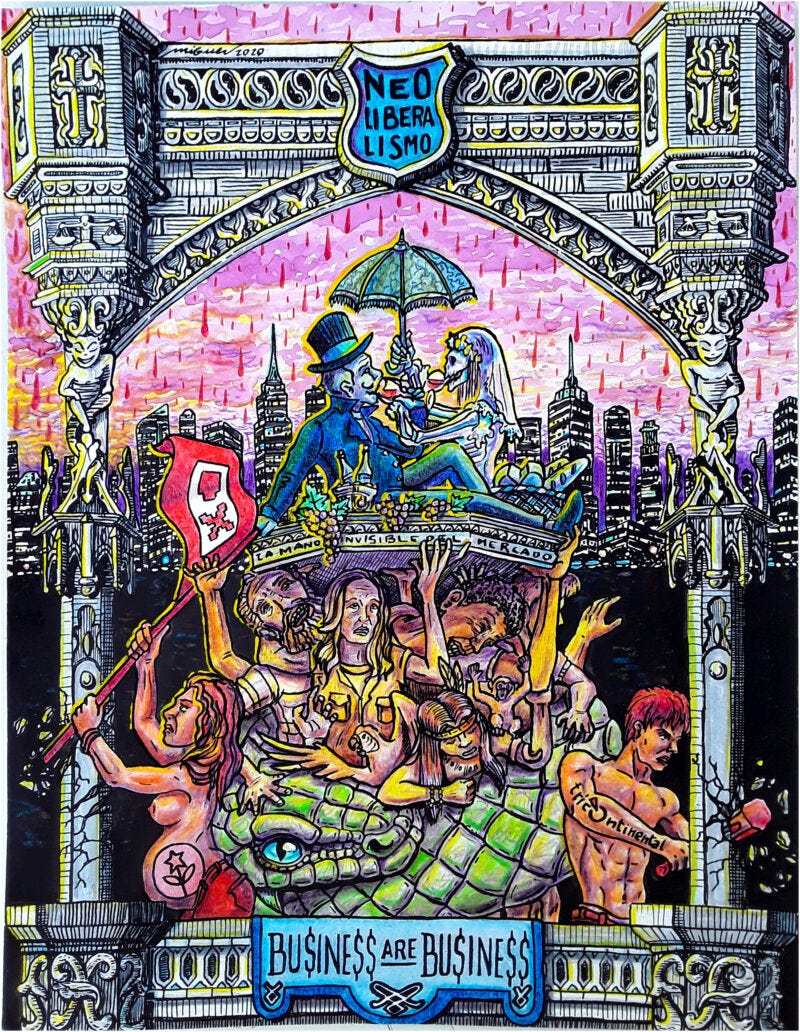

Below is a visual illustration of the polycrisis from a dialectical materialist perspective.

Now let’s look at the 3 case studies using the framework discussed in this piece. Note that this is just a brief application; each of these examples warrants its own piece given the complexity involved.

Palestine

In newsletter #12, we wrote about how it was frustratingly self-defeating that most liberals, even the well-intentioned ones, were stuck in this doom loop of being shocked and calling on “international law” every time an atrocity happened. They still don’t realize that liberal notions of “human rights” and “international law” are fantasies that were set up by hegemonic forces to delude people into becoming active participants in their own oppression.

Understanding historical cycles shows that these notions arose in a specific civilizational context — that of Western Enlightenment — and hence are tied to the goals and modalities of that system. This same philosophy was the foundation of imperialist conquests, the loot and plunder of the Global South, genocide against natives, etc.

At the same time, seeing how cycles end would also clearly show that no real change in history (read: resistance against oppression) happens through moral rhetoric. No system gives up power because the people it is oppressing can make a convincing argument. Power shifts and the creation of a new system is a chaotic, and almost necessarily, violent process. That’s not an opinion, that’s just history.

Without this, any support for Palestine is merely jumping on a bandwagon that is implicitly still hitched to the status quo.

For a more accurate analysis of the situation, let’s contextualize it across the three historical cycles:

Long-term: Israel is a manifestation of European imperialism, both operationally as a settler colony, and rhetorically with the colonial language of civilizing and democratizing a backward, unstable region. The clash of civilizations narrative to create the facade of a religious war is also consistent with the divide-and-conquer strategy that has been the go-to tactic of imperialists.

Medium-term: This probably gets the least attention. The issue did not start in 1948. Instead, the roots were set decades earlier at the end of WW1 when. In those decades, we were witnessing another cyclical shift. The US was taking over as the global hegemon, which opened up power vacuums across the Middle East.

For example, the new Saudi state was formed and chose to ally with the rising US as the first “ally” in the region. Even though the Saudi monarchy was staunchly anti-Zionist, and the US was firmly Zionist, the new Saudi state prioritized this alliance because it wanted to counter the growing influence of the Hashemite kingdom (aligned with the British) in the Greater Jordan area, the Mufti in Palestine (who was against the House of Saud controlling the Holy Sites), and the newly independent Egypt.

Over the course of the 20th century, Arab monarchies continued to align with Western interests, undermining the Palestinian cause, to gain political leverage against the growing leftist, nationalist, and pan-Arabist movements that threatened to reform the region.

Today, as US hegemony withers, those fault lines are opening again, and the political entities that arose, or were engineered, to meet the postcolonial interests of Western powers will potentially be undone (that includes Israel). The contradictions leading to the implosion of Israel are plain to see. It won’t be long before even its imperial allies turn the other cheek. The window of change is open.

Short-term: The energy crisis of the 1970s shaped the system that we still live in today. Given the energy-exporting nature of regional powers and the importance of the Palestinian region as a trade route, as well as a source of natural resources, this is the dominant dynamic that has shaped the politics. We won’t get into the details about Gulf states striving for decades to normalize relations with Israel, but it goes well beyond the “the enemy of my enemy is my friend (anti-Iran)” logic that most commentators boil it down to.

Lastly, the end of the neoliberal era is marked by the return of ideological politics. The Arab world, and with it the Palestinian cause, was a hotbed of ideological diversity, all striving to defeat imperialism in the region. Those movements were crushed and the past few decades have been a sterilized political lull. Now, as those medium-term cycle faultlines re-emerge, leftist, nationalist, pan-Arabist, and potentially other forms of politics, will tug at the core and inevitably reshape the region, liberating Palestine.

[Going to keep the climate change and Pakistan ones short as I have talked about them in other pieces]

Climate change

Long-term: We definitely have a philosophical problem of believing that human ingenuity, rationality, and technology can perpetually dominate nature. This isn’t just an economics problem, where ecology is merely seen as a commoditized input, but a literary, sociological, and cultural problem of hubris. The long-term contradictions here are clear: the more we exploit natural resources — e.g., the soil — the more fragile we make our civilization as those resources deteriorate, leading to us frantically exploiting more in an attempt to fend off disaster.

Similarly, while we try to dominate nature to feed our consumption needs which is supposed to make us feel good, our increasing detachment from nature increases loneliness, and exacerbates physiological and mental health issues.

Medium-term: During WW2, famous economist Simon Kuznets came up with the concept of GDP to measure sector-wise outputs in the economy and disruptions from the war. Through a complicated intellectual history of neoclassical economics, GDP became the core goal of the global economic system, even though Kuznets himself had warned against using it as such. Burn down a forest and replant some monolithic seedlings — GDP growth. Since we ultimately live in a material world, GDP growth is directly driven by increasing energy and material use as inputs, and more waste as outputs.

Our obsession with growth is what drives climate change and ecological collapse.

Short-term: The neoliberal era from the 1970s created an environment of deregulation and privatization, where large corporations and oligarchs could pursue profit unfettered by any social or ecological cost. At the same time, these agents and entities took over the state and other key institutions, leading to widespread lobbying and misinformation that undermined the climate cause despite consistent evidence. Even today, we remain stuck in this desire to “mobilize the private sector” — although as we keep saying, the return of the state as this cycle ends presents an opportunity for collective action.

Pakistan

This is one of the best examples of things that were formed to serve the needs of a specific cycle, and hence are most at risk of being undone as that cycle ends.

Long-term: Pakistan suffers from the volatile political concept that a nation-state can be formed by bringing together distinct communities under the banner of an idea — in this case, religion. On top of that, there’s the belief that liberal democratic institutions can simply be built through some education, imported technocrats, and foreign aid. This has proven to be nothing more than Einstein’s definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again. This whole phenomenon is inherently unstable, made considerably worse by the Westernization of Islamic discourse.

Medium-term: Pakistan’s geostrategic importance has made it an important “ally” (to put it politely) for Western powers, whether to contain Soviet or Chinese expansion, contain nuclear risk, or gain political leverage in the Muslim world. But as Western hegemony withers and the world fragments into more regional issues, the strategic value of Pakistan fades, and with it, the political and economic support that has served as crutches for the nation.

Short-term: Particularly in the neoliberal era, Pakistan has been stuck in the IMF-induced debt trap. Other nations in the Muslim world have moved on with their political alliances, neighboring South Asian countries like India and Bangladesh have surged ahead into totally different leagues, and Chinese patronage is getting flaky.

Today the country in the midst of deeply entrenched social violence along sectarian, ethnic, and political lines, a crumbling economy marred by the elite exploiting every piece of labor and natural resource that is available, and dwindling external support to keep the lights on.

A country that has by far the lowest salaries compared to neighboring developing countries, along with milk prices higher than Germany, electricity prices higher than the US, and facing deadly summer heatwaves would expect to see riots. But Pakistan is so fractured along sectarian, ethnic, and political lines that even this catastrophic cocktail of events can’t bring the masses together.

As a nuclear power with a large, young, and charged population, Pakistan should be on top of everyone’s fascism and global risk list.

___

Crazy things happen when historical cycles turn and the window of change opens up. This is that era. The world we live in, with all its issues and contradictions, wasn’t shaped overnight. And the undoing of it won’t be either. Every few generations there’s a chance to fundamentally reshape the world — this is our chance to make the most of it.

This is very well written note. My only point of disagreement would be that, as someone who is doing business in Pakistan, I see some area's of the country crumbling away, but I do see in a majority of circumstances lots of young people learning less from religious books and more from Watching Friends, House of the dragon and freelance work for people in Europe/America most of the time. I see these issues all the way in the Rural areas... and countries like China, Saudi, India all behind the scenes are pressuring the country to deregulate and liberalize trade which will happen soon so its not that pessimistic short-term/

As always, you have crafted a brilliant, organised, erudite and articulate breakdown. Many people across the world have presented and discussed these topics for decades and it will take many more before enough people understand what's happening.